Christine D, a trans woman who has been living with HIV since 1986. Credit: Andrea Houston

Antonio Cefaratti, who is speaking out and telling his story about HIV criminalization. Credit: Andrea Houston

A queer youth who survived a childhood of bullying got the opportunity of a lifetime as a summer intern at the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research (CANFAR).

His main project came to fruition on Aug 22. Stigma, a cocktail party at the Julie M Gallery in the Distillery District, showcased ordinary people living with HIV who have extraordinary stories.

How the intern, Benjamin Jones, came to this point is also an incredible story.

Originally from Belleville, Ontario, Jones came out at age 14. He says he quickly became a target for bullies at school and was regularly attacked for being gay. “Even before then, I was still the outcast.”

After high school, he ran away from home for two months, drifting from Kingston to Toronto and Montreal. “It really taught me that you can always find where you belong,” he says.

Jones, now 19, says he didn’t leave home because his parents were unsupportive. “My family was amazing. My dad and mom are the most incredible parents I could have asked for. But there was more I needed to see and do. I was so angry at the time. Back then, I really didn’t want to be gay.”

When he eventually went home, he set out to create a place where LGBT youth could feel safe and accepted in his less-than-accepting hometown. So he created the Belleville Youth Recreation Centre in 2011.

Partnering with the City of Belleville, he launched a drop-in space to give queer youth and straight allies a place hang out together, watch movies, play games and meet new people, twice a month.

That led to a prestigious scholarship from TD, honouring youth community leadership. Jones got $70,000 over four years and the pick of any university in Canada.

He settled on the University of Toronto, where he is doing a double major in immunology and global health. “I came to Toronto because I felt at home here. It’s accepting, and I felt safe.”

The scholarship also came with a summer internship, so he picked CANFAR. For the past two months, Jones has been organizing Stigma, a cocktail party and storytelling event. “I’m really interested in how we talk about unsafe sex. So I wanted to plan an event so people could see the reality of living with HIV through storytelling.”

He says inspiration for Stigma came from three friends who were living with HIV. “For my friends, it’s not the virus itself, but societal impressions and how they are viewed and treated.”

Christine D

Christine is an HIV-positive trans woman and former sex worker who has been living with the virus since 1986. Despite this, she is infectiously joyful and knows the perfect moment to crack an ice-breaking joke.

“I have always used humour in my life,” she says. “We have to laugh, with each other and at ourselves.”

Christine wasn’t always an activist. She started working with PWA (the Toronto People with AIDS Foundation) about four years ago. There, she was encouraged by staff to begin telling her story.

She often talks about intersectionality and how women with HIV, trans women and sex workers are hit extra hard by stigma.

Statistically, trans women with HIV remain invisible, she says. Most stay silent and live in isolation. She says more allies are urgently needed. Disappointingly, she says, the stigma from within the broader gay and lesbian community is still a big part of the problem.

“The stigma within the [gay] community is huge,” she says. “I hear comments from gay men on Church Street all the time. I hear them making comments behind me. I always wonder if I should turn around and say something, like, ‘I’m more woman than you could ever handle and more man than you will ever be.’”

“Trans women, we need to get out there and talk about what it’s like living with HIV, because it’s still here,” she says. “It can happen to anyone. No one is immune.”

Chantal Mukandoli

In 1994, when genocide was raging in Rwanda, Chantal Mukandoli survived a brutal gang rape that gave her both HIV and a pregnancy.

Her daughter was born with HIV, and she has not seen her since 2006.

That’s when Mukandoli came to Canada to speak at the International AIDS Conference. Her presentation discussed the reality of living with HIV in Africa and how the the effects of the genocide are still being felt in her home country.

“I lost everything,” she says. “I lost my husband. I even lost my memory. And I lost my family.”

Mukandoli says she is grateful to have been allowed to stay in Canada, where she received an education, medication and treatment. But she did not escape the stigma that comes with being HIV-positive.

“My daughter is not here with me,” she says, “because I don’t have a job with enough money to support her. I can’t go back to see her, but we talk on the phone. That makes me very emotional. I get lonely and think about my children.

“So I have devoted my life to talking about HIV and AIDS,” she says.

She says she is focused on highlighting a grave problem in Canadian law: people with HIV should not be criminalized if they fail to disclose to their partners.

“In Canada, if you don’t tell your status, you are a criminal,” she says. “Stigma prevents people from disclosing. I talk a lot about how stigma affects women.”

Despite her longing to be with her daughter, Mukandoli says she can’t go back to Africa. Staying in Canada means her survival, she says.

“I can’t ever go back,” she says. “To have medication for HIV — it’s not easy to get, and it’s expensive. Also food: in my country, they don’t have any food. So some people stop taking medication because they have nothing to eat. I stay here for my health.”

Her message is a simple one: “HIV does not kill people; stigma does. I am healthy. I have treatment. But the stigma I get from being a woman with HIV is killing me.”

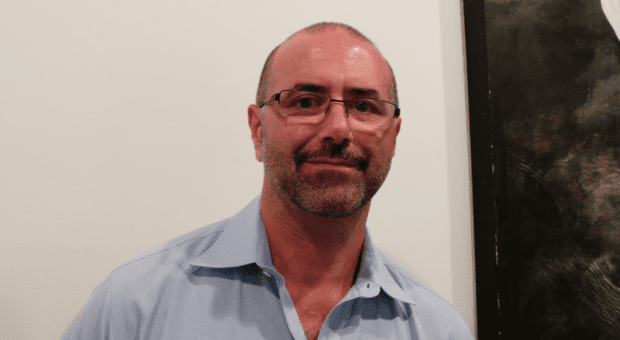

Antonio Cefaratti

Growing up Catholic meant Antonio Cefaratti stayed closeted for most of his young adult life.

When his marriage ended in 1994, he was finally able to be the gay man he always wanted to be.

“I spent a long time making choices for everyone but myself,” he says. “In Roman Catholicism, that was what you did. There was so much guilt and shame. My parents didn’t even know the word ‘gay.’ But within two to three months, my parents were great. My mother welcomes everyone into her home. Things were good.”

Then, in 2009, everything changed. Cefaratti contracted HIV. For two years he kept it a secret, not wanting to admit to even himself his new reality.

In 2010, a new partner entered his life, and with the relationship came new experiences. “It was a crazy relationship. There was lots of drinking and drugs. We partied together. I was working through a lot of stuff.”

One night, they had unprotected sex. “I didn’t disclose. He tested positive in 2011. And he pressed charges.”

“At the time, I thought that if I didn’t have an orgasm, I couldn’t infect people,” he says. “I was totally wrong, but that’s how our mind works.”

Cefaratti was charged with aggravated sexual assault and attempted murder. He was terrified.

“I never had any dealing with the law before in my life. It was incredibly difficult.”

Thankfully, a former partner reached out to help him by finding a lawyer and offering support. Cefaratti got 22 months in prison, most of it spent in solitary confinement.

“When I was first incarcerated, a couple of the inmates got a hold of the charge, and I was beaten to shit after two weeks.”

While incarcerated, he spent time in five institutions. “While receiving mental-health treatment, I was basically told that I should know better,” he says. “I was told that I was a narcissist. This was by professional psychologists.”

In March 2013, he was finally released on three years’ probation. “While inside, I knew I wanted to tell my story. I want to tell people that are HIV-positive that it’s easier to disclose than go through what I went through.”

Still, he says, HIV should not be criminalized in the first place. Nondisclosure is a health issue, not a legal one.

If people with HIV are criminals, he says, the rest of the world treats them that way. “Treating people like this is terrible.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra