Kent Monkman is one of the most influential artists of our time, so I want to open my interview with the Cree artist with a hard-hitting question: “Why are Cree people obsessed with chisk (a Cree word for ass) and farts?” I wait with bated breath. Every passing millisecond has me questioning my decision-making abilities and interview skills. I had gambled on our shared Cree connection. Have you ever wondered what you would ask your hero if you were presented the opportunity? Did you think it would involve flatulence? Me neither. Monkman smiles. I release a grateful exhale. Monkman resumes a baseline gravitas, as he acknowledges his family. “I remember my great-grandmother telling us these fart-oriented wîsahkecâhk (trickster) stories.”

Monkman is a multidisciplinary superstar in the art world with a career that spans three decades. Most recently, Monkman became an officer of the Order of Canada, among numerous other awards and honours. Monkman’s work has been exhibited around the world, including at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Musée des beaux-arts Montréal, the Royal Ontario Museum and Palais de Tokyo. Monkman has created a number of site-specific performances and has had two nationally touring solo exhibitions, The Triumph of Mischief (2007–2010) and Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience (2017–2020). In short, he is a living legend.

We recently met over Zoom to discuss another legend, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. Miss Chief was originally created as a persona of Monkman’s. Since her first appearance in the painting Artist and Model in 2002, Miss Chief has transformed and taken on a life of her own through installations, performance art and film. In one painting, The Affair (2019), Miss Chief explores her sexuality with a Canada goose, one of her many lovers. Miss Chief added another feather in her bonnet when she wed Jean Paul Gaultier in a surprise 2017 performance at the Musée des beaux-arts Montréal.

Despite her many appearances and escapades, we know very little about Miss Chief’s origins and history. The Memoirs of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, the new two-volume collection, sheds light on this elusive figure. Miss Chief makes it clear that she’s not about to give it all up for free. “You haven’t brought me tobacco, blankets, horses, not even a pack of chewing gum,” she writes in the memoir’s opening pages before reluctantly agreeing to share some of her story. Much of Miss Chief’s story functions as historical text recounting the creation of the universe according to Cree cosmology, as well as Cree life prior to and following European colonization of the Americas. The memoir is a deeply Cree and gloriously queer account.

Monkman is joined in our interview by his longtime collaborator and co-author of the memoir, Gisèle Gordon, a settler media artist and writer whose award-winning solo work has been featured around the world. Gordon has worked with Monkman on a number of projects, including co-authoring the exhibition text for Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience, as well as the authoring the exhibition text for Being Legendary.

Artist Kent Monkman and collaborator Gisèle Gordon, co-authors of “The Memoirs of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle: A True and Exact Accounting of the History of Turtle Island.” Credit: Aaron Wynia

Kinship and connection are central themes in the memoir. Both Gordon and Monkman readily acknowledge the relationships that have inspired and supported this work. Throughout the production of the memoir, Gordon and Monkman worked closely with a small team of Cree knowledge keepers and language speakers, including Dr. Keith Goulet (Nehinuw, Cumberland House Cree Nation), Floyd Favel (Nêhiyaw, Poundmaker Cree Nation), Dr. Belinda Daniels (Nêhiyaw, Sturgeon Lake First Nation) and actor and filmmaker Gail Maurice (Beauval). “They’re all either artists or storytellers themselves, and they believed in this work and what Kent has been doing for decades with his paintings,” says Gordon, who moved from the U.K. to Canada as a child. “We’re very, very lucky to have such wisdom and support.” Of course, support doesn’t mean the team always agreed with each other. “They told us if they thought we were wrong, which was really what we needed,” Gordon says.

It was Favel who instructed the duo to develop a creation story for Miss Chief. Monkman and Gordon were advised to use the term “legendary being,” which signals that she is not a fictional character and does, in fact, have a sacred lineage. The memoir begins with the cosmic birth of this legendary being who one day finds herself barrelling toward earth and assuming a human form along her descent. Miss Chief Eagle Testickle arrives with erotic desire and a clear set of instructions: “There will be beings in the future, two-leggeds, who require our assistance. You are to live with them, learn their ways, hold their stories and become legend with them,” the memoir recounts. “Above all, you must love them.”

Despite inhabiting Miss Chief’s perspective jointly—“We have both evolved to think with Miss Chief’s brain together,” Gordon says—the co-authors found there was still so much to learn about the legendary being. “Writing this book filled in a lot of gaps,” Monkman says, “in terms of understanding the character and her purpose.” According to Monkman, Miss Chief is both participant and witness. Her story does more than recall historical events, it provides a felt account that reconnects readers with the humanity of historical figures. “She’s making history feel real,” Monkman says. Miss Chief’s fantastical history is unique. In recent years, I’ve noticed a growing fascination with science fiction, speculative fiction, settler dystopias and decolonial futurity in academia and the arts. While other characters zip off toward an unknown future, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle is more likely to be found in an 18th- or 19th-century scene. So what is Miss Chief’s relationship with the future and world-building?” Miss Chief is timeless, Gordon says. For Miss Chief, the past, present and future exist as one word. Time expands and contracts like an accordion. The memoir, Gordon says, “is told in a linear way because [Miss Chief] knows that she’s speaking to human beings and that’s the way that they can comprehend time.”

Gordon says they made a conscious choice to turn away from dystopian narratives. She and Monkman wanted a counterpoint anchored in radical love. “We’re at a time where dystopian fiction is completely taking over our imagination and cultural landscapes,” Gordon says. “And there needs to be some alternatives to push back against that, because if we keep internalizing them, it’s going to be even harder to imagine a future with connection and the deep wisdom that can guide us.” In other words, she concludes, this memoir is “against dystopia, against nihilism.”

And yet, as a witness to history, Miss Chief remains very much concerned with the future. “When the gaze is reversed, it’s about centring our values and speaking to the world from this Cree universe,” Monkman says. “In terms of moving forward, the world missed this opportunity to learn from us.” Without any hint of judgment, Monkman makes this point as a matter of fact. European settlers-cum-Canadians’ devaluation of Cree and other Indigenous peoples is the bedrock of Indigenous-settler relations that has facilitated assimilation, erasure, dispossession and attempted elimination of the original peoples of these lands. The shape of the future(s) very much depends on our willingness to meaningfully engage with these violent histories. When Monkman describes this book as “a gift to the world,” he gestures toward the ways this text provides guidance on reimagining and remaking the world based on Cree and Indigenous value and knowledge systems.

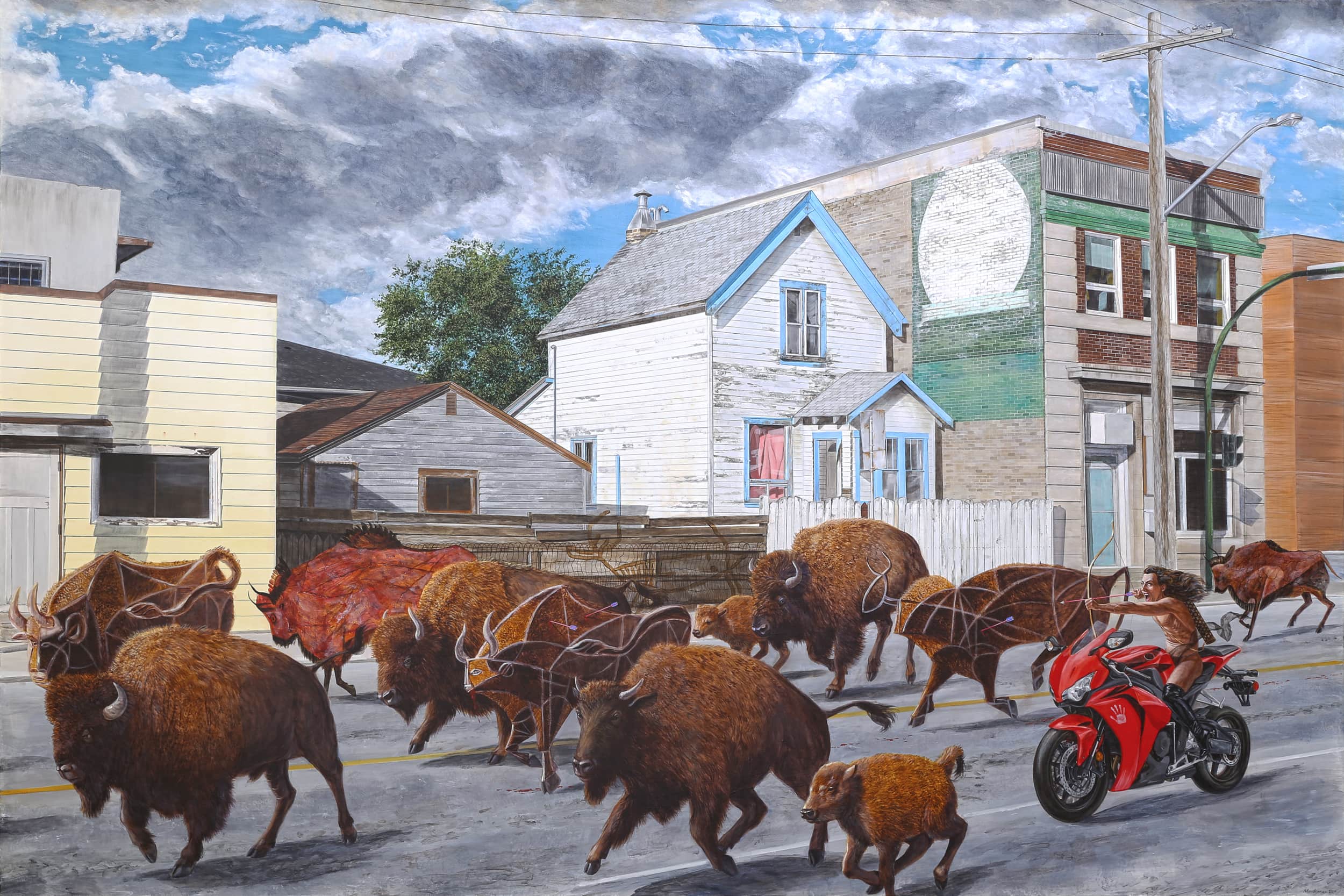

“The Chase,” 2014. Credit: Kent Monkman

One of the things I appreciate most in the memoir is the inseparable connection between Cree identity, gender diversity and sexual expression. This is particularly poignant when accounting for Canada’s systematic suppression of Indigenous gender and sexuality. “My work has been about decolonizing our sexuality and decolonizing our way of understanding gender because our cultures got compressed through this very aggressive colonial project,” Monkman says. “My project has been to remove the shame around our sexuality, around our bodies.”

The shame around Indigenous bodies and sexuality is in large part attributable to the presence of Christian churches. The clergy, Monkman says, “basically became chroniclers of Cree life.” That perspective still informs contemporary understandings of Cree “traditions” around gender and sexuality. The second volume of the memoir grapples with the devastating impact of Canada’s Indian residential schools where the gender binary was violently installed and rampant sexual violence against Indigenous children was enacted by clergy. Here, Monkman and Gordon dispel claims that gender and sexual conservatism are traditional to Cree people. In fact, the feedback the pair received after submitting an early draft to the knowledge keepers was “make it funnier, make it sexier.”

I’m certain that Cree people talking about their kookums comes as a surprise to absolutely nobody; it was only a matter of time before Monkman and I introduced our grandmothers to the conversation. It was in this context that I was surprised to hear about the knowledge holders’ instructions to make the book sexier. My late kookum was someone who, on one hand, was weirded out by a musical group named the Barenaked Ladies, while on the other hand, would laugh with me about bestiality jokes. Similarly, looking across two generations, Monkman identifies the role of the residential school in shaping both humour and sexuality. He recalls his grandmother who attended residential school, “I always saw that sense of humour in her, but it was also countered with this degree of Christian conservatism.” Her mother, however, Monkman’s great-grandmother, “never went to residential school and wouldn’t think twice about telling us kids all these dirty and funny stories.”

I nod thinking about my late kookum’s humour. I feel more akin to Monkman than I should, but I can’t help my fascination with our shared ancestral connections. Monkman is a member of Fisher River Cree Nation, a First Nation formed when a segment of my community, Norway House Cree Nation in northern Manitoba, relocated to central Manitoba in search of economic stability with the decline of the fur trade in the late 19th century. A rather roundabout connection, but one that I celebrate nevertheless.

The second volume offers a semi-fictional account of Monkman’s familial history. As he describes his great-grandmother and grandmother, it evokes two matriarchs spanning two generations at the head of Miss Chief’s chosen family. “They’re literally like two of my favourite human beings in the world,” Monkman says, beaming. Imagining these women from Monkman’s perspective paints a clear picture of two remarkable women confronted by the full force of colonial power in the 20th century, yet somehow managing to anchor their family. Monkman’s great-grandmother was born in 1875 and lived to be 100 years old before passing away in 1975. He tells me that she was older than the Indian Act (established in 1876) and witnessed and survived the violent installment of colonial legislation designed to suppress Cree life. “They were such strong individuals,” Monkman says. “I looked up to my grandmothers.” Acknowledging the ways settler society denigrates Indigenous women, Monkman sees Miss Chief’s memoir as an opportunity to “rebalance and put our women forward.”

I choose to wrap up our conversation with a very human preoccupation: the matter of failure and success. The second volume begins in the wake of Miss Chief’s self-described failure to stop the formation of Canada. Even as a legendary being, Miss Chief must contend with regret and pain that comes with her inability to alter the course of history. Yet, she is relentless in her desire to protect her people. I had to know how Monkman and Gordon imagined Miss Chief conceptualizing failure and success. “We kind of liked the idea […] of the flawed trickster, who would sort of mess things up and sometimes be successful and sometimes not,” Monkman says. “I think she would prefer it if she’d been able to change the course of history as she saw it happen.” Gordon adds, “I think she would say something like, ‘There is no failure if you keep trying and as long as you keep standing up, stepping one foot forward, always trying to love despite how incredibly difficult it is to find connection right now. As long as you keep moving towards that path of goodness, miyo pimatisiwin (an exemplary life), there is no failure.’”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra