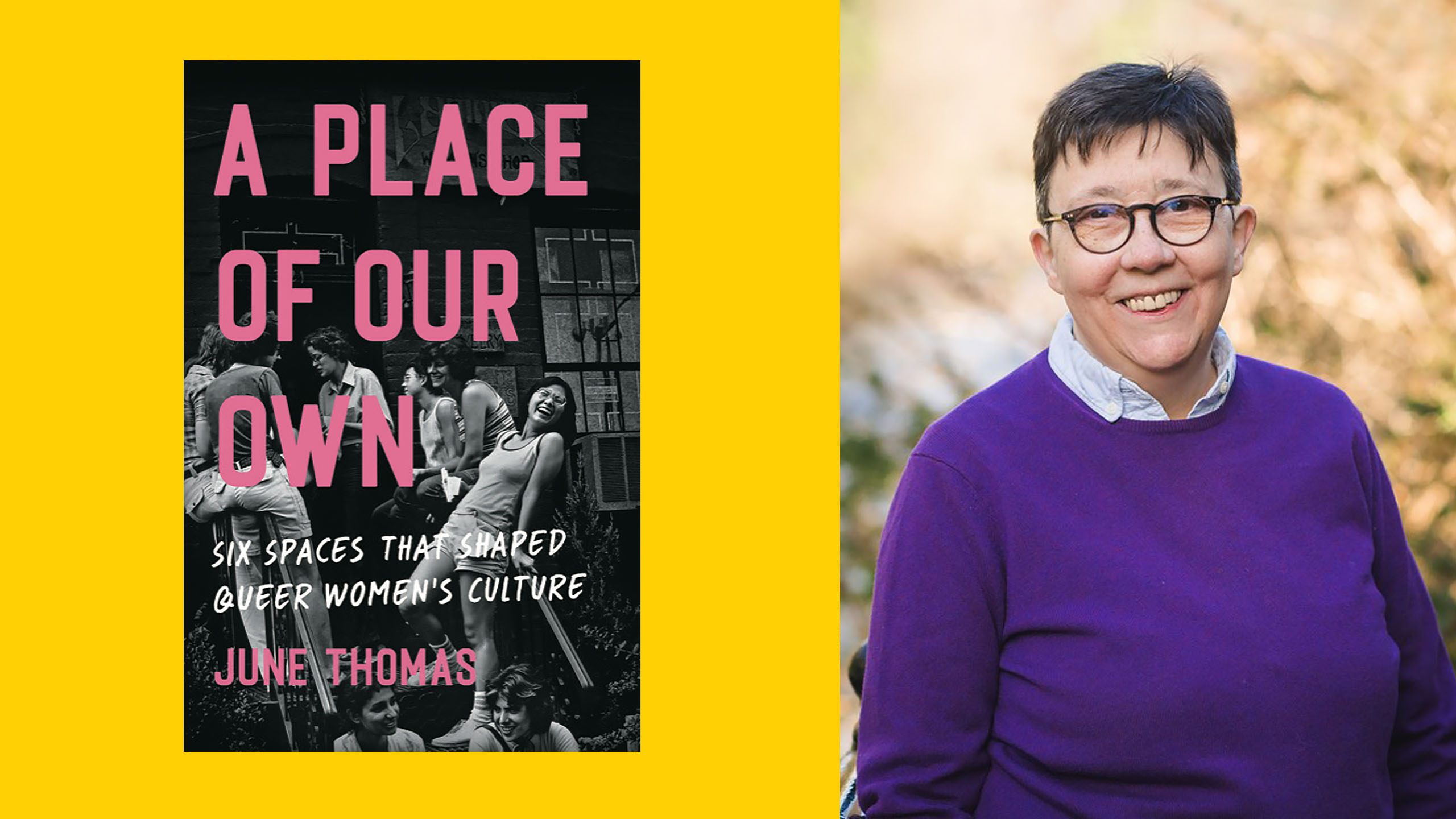

In her first book, A Place of Our Own, British writer and podcaster June Thomas tells the stories of six significant lesbian spaces throughout history—from the 1950s through to the present. “Spaces” are defined loosely throughout the book: it captures the early days of lesbian bars, the trials and tribulations of feminist bookstores, the fun-loving game of softball, the creation of a lesbian-feminist culture in rural and secluded land, the educational space created within feminist sex toy stores and the queer freedom of vacation destinations.

Each experience Thomas details is uniquely its own. Yet through each story, readers continue to learn and understand how large of a role these spaces have played in shaping queer culture. Thomas also speaks on her own relationship to these queer places, namely during the 40 years she spent in the U.S. after having moved there from England in the 1980s.

Here, Thomas speaks with Xtra about the triumphs and pitfalls of queer women’s spaces, the unabashed fun of lesbian softball and what it means to build a utopia.

Many of the spaces that you focus on in your book are located in the U.S., despite the fact that you were born in the U.K.—and currently live there. Can you speak on your experience moving to the States in your youth and how that affected your own identity as a gay woman?

I guess when I came out to myself, I realized that I was going to have a separate social life. I still got along with my college friends; I wasn’t estranged from my family or anything drastic like that, but I just knew there was going to be a parallel social life in gay spaces and queer spaces, lesbian spaces. I grew up in Manchester, where people often moved away. People were more likely to have visited Canada than they were London because they would visit [loved ones] who had emigrated abroad.

To me, the U.S. was the queer homeland, which, given the current politics, is a strange thing to think about. As I mentioned in the book, [when I moved to the States] I found this gay travel guide that was just absolutely crammed with meeting places and most of them were for men. Most of them weren’t relevant to me. But there was something sort of aspirational about seeing, “Oh, you know, there’s places.” Even though I was in the States for 40 years, in all that time, I probably went to five to 10 of them.

Still, in Britain at that time … you had to call people to get lists of gay pubs. It was much more hidden. And so, for me, the States was almost like the promised land of queer culture.

Why did you want to focus on spaces for lesbian and queer women?

As a lesbian and a queer woman myself, that’s always been my priority. These spaces were also my spaces—not every chapter, but in many of the chapters, I talk about my own experiences in these places. Before the internet, it was much harder to find out about what was going on in your own city, much less anywhere else. Because the queer papers, which was where most of the gay and lesbian stuff was talked about, and then the feminist publications—you could only get them in a few places. It wasn’t like you could go down to the local newsstand and find Off Our Backs or gay community news. I was interested in journalism, and I worked at Off Our Backs, and so we did exchange subscriptions with a lot of publications. I’ve had that advantage of knowing about projects and knowing about places as they were kind of covered in the queer press and the feminist press. I found their stories to be interesting, and yet I didn’t feel that people knew about a lot of this history. So it was really the fact that queer women’s stuff is often under-covered.

Your book focuses on lots of spaces that aren’t bars. What was the process like of narrowing your book down to six different spaces?

A couple of people, having read the book, said, “Oh, you’re down on bars.” And I don’t necessarily agree with that, but I feel like people are generally aware of some bar history, so that felt like there was less urgency to write about it. The others, like [feminist] bookstores, were so important to me, and I wanted to be sure to include their role, not only as a place to buy books but as a community centre. I’d never been to a softball game until I was writing the book, and then I was like, “Why have I not been here before?” Obviously softball is a huge part of many queer women’s lives every summer. The story that I tell about softball in the book is very specific, with specific examples of times when it became a politicized space. But all around the world there’s some equivalent. It may not be softball—in a lot of countries, it’s soccer, rugby—I’m told that in Australia it’s field hockey. But just that place where you can have that camaraderie, that teamwork and that physical expression.

Lesbian land felt like a super interesting story to me, but also, I think, in a very specific way, because many of the lands are now trans-exclusionary, and I understand exactly why people don’t want to explore them more. To me, there’s still so much history that’s super interesting, such creativity that came out of it that I didn’t want to ignore it. [With feminist sex toy stores] I’m a wee bit prudish … it was a little hard for me to be researching toy stores. But, like, how can you talk about women’s liberation, queer liberation, without sexual liberation?

With vacation destinations [such as Provincetown, Massachusetts; female music festivals; cruises and more] it took me a while to realize that’s a place that’s been really important to me. And even though now they’re quite expensive and it’s becoming less of a common experience, it’s still something that provides kind of a unique refuge.

Your chapters focus equally on the highs and lows of experiencing these different spaces. Why was it so important to include just as much of a focus on the negative aspects of these spaces as you did on the positive impacts they’ve had on the community?

As a journalist, you have to tell as much as you can of the whole story. That’s the theory. And in practice, it’s very hard, because we come with our own connections, our own experiences. I wanted to celebrate the spaces I wrote about, but not idealize them. It was shameful, for example, that bars so often excluded women of colour, especially if they were without any white women in the group. But did I ever go into those bars? And did I ever notice? I mean that was my failure too. To be clear, if I had been with someone and they hadn’t let them in, I hope I would not have been so passive. But I never did sort of go around and say “Is anybody being excluded?” So it’s as much on me as the community generally.

Maybe you can believe that many of these places are utopias, and in some ways they are, because finally there’s somewhere where we can show affection, where we don’t have to be so guarded, and that feels so wonderful. But they aren’t paradise. If we fail outside our community, we so often fail inside the community. And I also think that that’s something that we learn from. Things do get better and we do change our behaviour. And that was a larger narrative of the book: It was about our evolution as a community and as individuals. It felt important not to whitewash history.

Reading your book, I was fascinated by your chapter on lesbian land, specifically due to the projects’ many shortcomings (women’s lack of practical skills, financial arguments, interpersonal conflicts, etc.). Why was it important for you to draw attention to a movement that’s embedded with so many conflicts?

Those conflicts actually don’t feel that negative to me. A lot of women who went to the land always said that one of the things you can do here is kind of deal with tough feelings and experience conflicts and find ways of resolving them.

Women who went to the land wanted to build a new lesbian nation, and I think the failure there was their being trans-exclusionary. These are women who are white, cis women, but they are poor, they have very little access to technology, to the internet, to medical care, to dental care. They have very little privilege [in other ways]. But they deny things to people who need it. So that to me is the flaw in that chapter. And it’s not all of them, but because many of the lands are trans-exclusionary, I think there’s a tendency to not want to even engage with them, to know about them and their history. And I did want to kind of bring their history to light, because—perhaps this is a little condescending on my part—but I think the issue is that they have been cut off in a way. They cut themselves off intentionally and then because new women haven’t moved to the land for the most part, they haven’t been exposed to new ideas, to our expanded views of gender, of sexuality. If my personal views had frozen in 1985, maybe I’d have that same view, but they haven’t. And so it felt important to share what to me are the good parts of lesbian land, as well as what feel like the very negative parts.

You also discuss the negative aspects of lesbian separatism, which often excludes trans and non-binary folks. Where do you think we’re at with this today? Is lesbian separatism still prevalent and playing a role in lesbian establishments’ disregard for trans and non-binary folks?

I think it’s definitely gotten better. In many ways, lesbian land communities survived longer than bars and bookstores and toy stores and some of these other locations, but they have not evolved. As women get older, they can’t live on the land because even though they did eventually make them somewhat more comfortable, they’re not terribly comfortable spaces, and they’re not terribly suited to women as they get older and are less able. So basically, they’re not expanding. They are coming somewhat to the end of their original life as communities.

Many communities—not consciously—have tried to be more diverse, but for various reasons, they tended to be white spaces. But from what I hear, there are more and more trans and non-binary-led rural communities because they’re not cutting themselves off in the way that people were three decades ago. We do have the internet now, and life is cheaper in the country, and you can spend more time on creativity and on healing, which goodness knows we need more than ever now. So I think I do see signs of [development], but I also didn’t want to lose that history of why those women went to the land, what they did there and then why they got stuck in a way.

A common issue called out in your book is how many of these spaces reject women of colour. Can you speak to that a little bit?

I’m not sure “reject” is quite the right word, but it’s not altogether wrong. I think certainly spaces have not been as welcoming as they should have been, could have been and need to be. And this is something that straight bars do too, or that men’s bars do too. I think lesbians and queer women maybe talk about it more, because we do bring politics to our whole lives in a way that not every community has traditionally done.

We know that in the past, many bars did things like monitor how many women of colour were in the bar, and if it was “too many” … honestly, even talking about it makes me uncomfortable. But that’s something from our history.

With the land, it wasn’t so much that they were rejecting women of colour, but they didn’t necessarily try as hard as they might have to understand what women of colour needed. The women living in the land were always trying to bring in more women because they could obviously see that their communities were shrinking.

And then with vacation destinations, it’s more of a kind of financial exclusion that people of colour face. Those vacation spaces tend to be quite white because of financial exclusion.

You note that the importance of lesbian or queer businesses is not the physical establishments themselves, but the community built within them. Do you believe that these established communities can live on today if these independent-owned businesses continue to disappear?

It’s true that the internet has given us a lot of what these spaces used to. [They are] making that initial connection, and that feeling of ‘I’m on my own” is much less prevalent. But I also think [queer women] want to meet in real life in spaces.

Even with all of the terrible political stuff, the anti-gay and especially the anti-trans stuff, there are more places [today] where we can do the sorts of things that we used to only be able to do in one place. I think that’s a matter of evolution, the community is evolving, the kind of places we hang out in is evolving. But I do think we still need those spaces if at all possible, wherever they may be.

What advice do you have for young or recently-out queer women wondering where to find community today?

Bookstores, just by their nature if it’s a political bookstore, if it’s a feminist bookstore, a radical bookstore, part of the mission is to connect people, as well as to sell things. I just think that’s such a welcoming and such an inclusive space. If it was summer maybe I’d also suggest a softball game or some kind of queer sporting event, because it’s outdoors, it’s healthy.

Any final takeaways?

I just want to celebrate these places and tell people about them. I didn’t want to idealize them, it was important to tell the whole story of the good and the bad. These places are so important to us that we hold them to higher standards than anywhere else that we do our drinking, our shopping, our vacationing. We want them to be perfect. And that is so hard. But we do that because we love them and we need them so much. So I just kind of wanted to emphasize how much joy these places bring, how much fun I’ve had in these places, and how much I’ve learned and how much I love them.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra