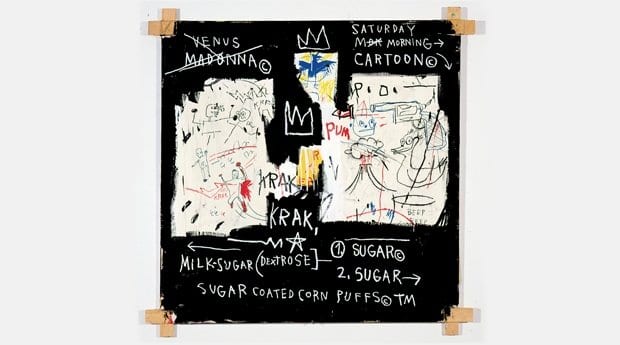

A Panel of Experts, 1982. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat / SODRAC (2014). Licensed by Artestar, New York Credit: Lizzie Himmel

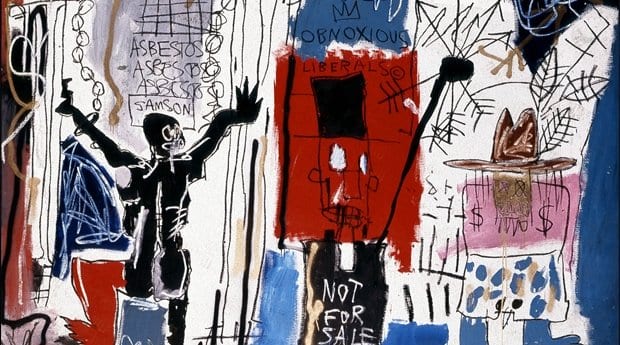

Obnoxious Liberals, 1982. The Eli and Edythe L Broad Collection © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York Credit: Lizzie Himmel

Horn Players, 1983. The Broad Art Foundation © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York Credit: Douglas M. Parker Studio

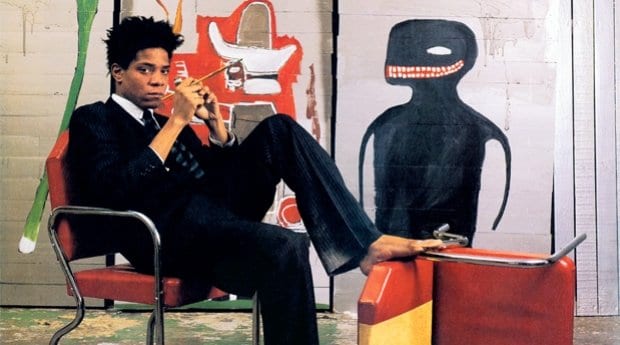

Jean-Michel Basquiat was many things during his short life. The half-Haitian, half–Puerto Rican provocateur was equal parts musician, poet and cultural critic, in addition to being one of the late 20th century’s most celebrated painters. Born into a middle-class home in Brooklyn, he ran away as a teen, living on the streets and selling painted T-shirts and postcards to support himself. At 16, he became part of the informal graffiti group SAMO, spray-painting buildings across Lower Manhattan.

After a solo show with Annina Nosei gallery in 1981, he was profiled by Artforum and his career went supernova. Fuelled partly by a boom in Neo-Expressionist art, his work began selling for huge sums. Soon he was showing internationally, palling around with Andy Warhol and (briefly) dating Madonna. But a combination of lifelong emotional trauma and the substantial wealth his art career generated led to a serious heroin habit. He died in 1988, at 27, of an overdose.

Given Basquiat’s stature, it’s surprising Canada has never seen a major exhibition of his work — until now. A current show at the Art Gallery of Ontario, assembled by Austrian curator Dieter Buchhart, features 86 pieces. Pulled together in less than a year (a very short time for an exhibit of this magnitude), the works have been drawn almost entirely from private collections.

“I like to say that they aren’t just coming from private collections, but from very private collections,” says Shiralee Hudson Hill, interpretive planner for the show. “Assembling them has been no mean feat. With some shows, you can just call up an institution and ask to borrow 10 pieces by so and so. But Basquiat’s works mostly live in people’s private homes. The fact they are coming into public view is a huge deal.”

Organized thematically, the show touches on Basquiat’s transition from street to studio, his portraits of African American heroes, his collaborations with Warhol, and his work around racism and reclaiming history. Dubbed Now’s the Time, the show feels eerily current, particularly his treatment of police brutality in Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart). A friend and fellow graffiti artist, Stewart was severely beaten by police while being arrested for spray-painting in a subway station. He spent 13 days in a coma before dying in hospital. Two years later, an all-white jury acquitted the six officers charged in his death.

“I always have to pause when I say the name of the painting because my tongue trips and I want to say ‘Michael Brown,’” says Hudson Hill, in reference to the unarmed teenager gunned down by officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri, last summer. “As a black man and a graffiti artist, Basquiat was really shaken up by the incident because he knew it could have just as easily been him. You get shivers looking at this work because you realize how little has changed in the last 30 years.”

Another aspect of Basquiat’s work that feels very current is his mixing of styles and influences. Paralleling the sampling and scratching of early-1980s DJ culture, his imagery, from boxing to baseball to hip hop to art history, feels equally at home in the age of the mashup. Building on Warhol’s pop iconography of Marilyn Monroe and Campbell’s soup, Basquiat reinterpreted the gesture with such figures as Joe Louis, the Mona Lisa and the one-dollar bill. In a talk at UC Berkeley, Tamra Davis (who profiled Basquiat in the 2010 documentary The Radiant Child) suggests that the range of experiences that shaped him as a person made him a ready receptacle for a variety of influences as an artist.

One part of his identity, however, is often forgotten or erased. Like his trademark dreadlocks and famously huge dick, much is made of his numerous affairs with women. But his bisexuality is mentioned only occasionally, most notably in Phoebe Hoban’s biography Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art. Based on interviews with friends and acquaintances, the often salacious book suggests that not only did Basquiat have several relationships with men during his lifetime, but he was rather open about them. His sexuality was also, apparently, part of the reason he left home as a teenager: after his father found out, life became unbearable.

So what happens when we apply a queer lens to Basquiat’s work? Does knowing that the person who painted these works also fucked men change our understanding of them? Or is it irrelevant, since he didn’t address the subject? Since the artist himself didn’t discuss the relationship between his sexuality and his creative output publicly, can we say anything concrete about it? I’m not sure, but there are two things we can conclude: first, identity is often more complex and unstable than it appears at first glance; and second, when someone achieves fame, his identity is often reworked in a way that better serves the people telling his story than the subject himself.

Village Voice critic Ernest Hardy addresses the issue in his writings on black male sexuality and “straight-washing”: the posthumous erasure of queerness in figures like Basquiat and Malcolm X. Hardy argues that since black artists are often fetishized as subversive or primitive in their work, their lives must then be depicted in more palatable ways to make them acceptable to the mainstream art world. During a 2011 talk on the subject, called Don’t Believe the Hype, Hardy said, “Maybe our culture can’t take who Basquiat is.” For the record, the AGO declined to comment on the subject.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra