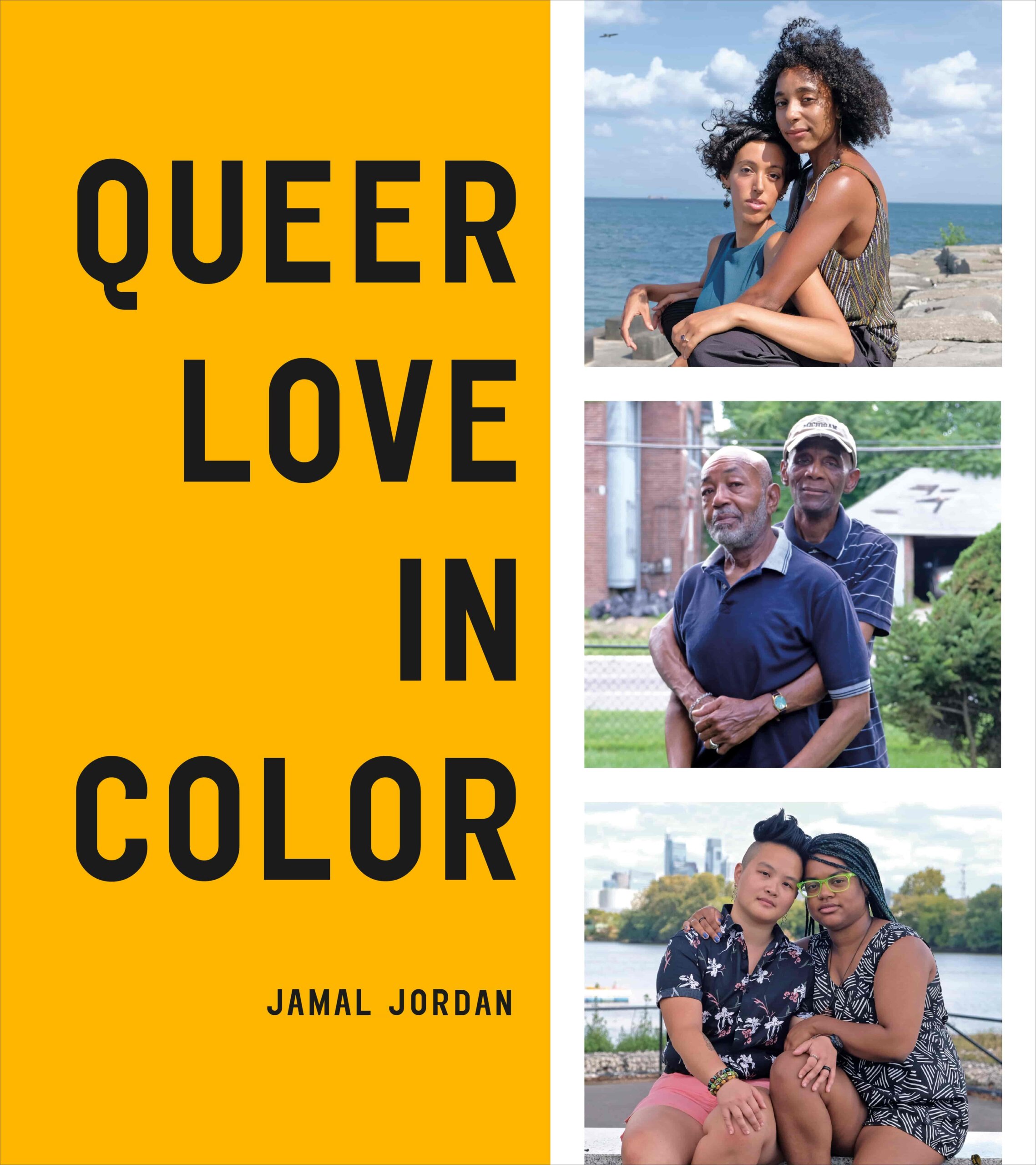

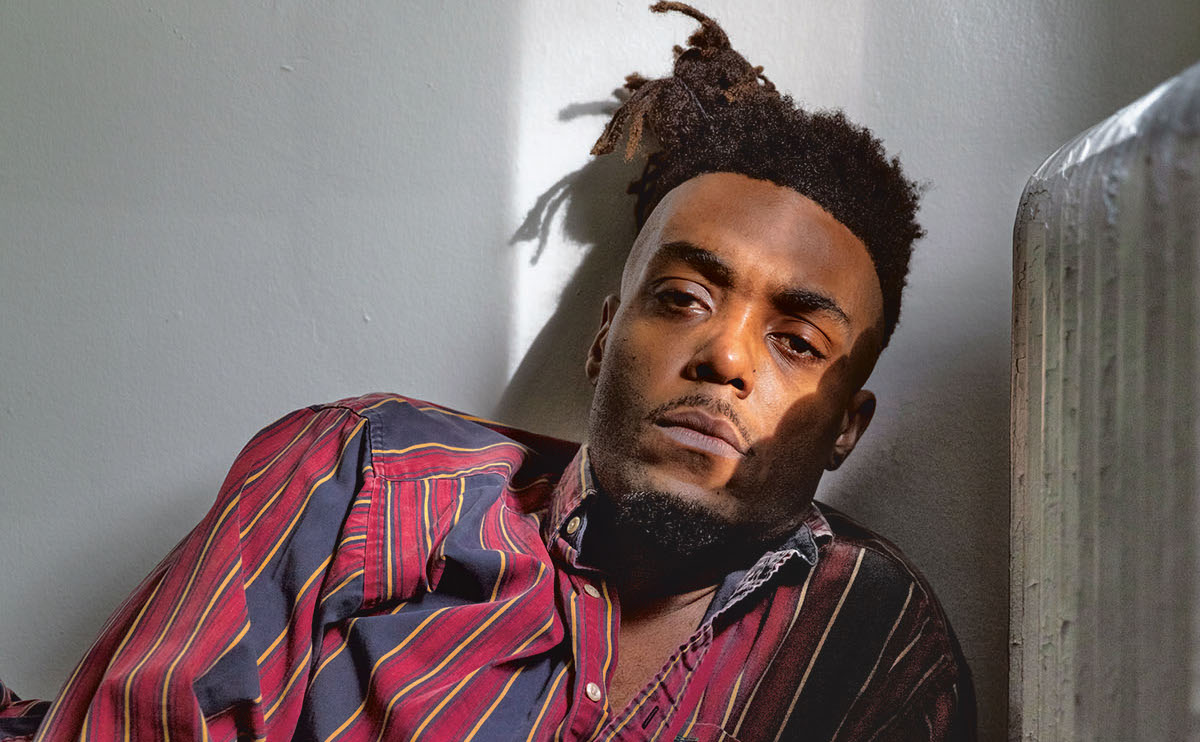

“Why do no gay people look like me?” This simple question tormented Jamal Jordan as a teenager in Mobile, Alabama. The search for an answer helped inspire Jordan, now 31, to embark on a career as a photographer and documentarian. In June 2018, Jordan wrote an article for the New York Times, “Queer Love in Color,” that profiled six Black queer couples using photography and text. The story went viral, inspiring him to delve deeper into the love and pride of queer couples of colour.

Jordan’s forthcoming book, Queer Love in Color, is a compelling collection of stories and photographs of couples and families around the world. Among them are septuagenarians Mike and Phil, who met each other at a Detroit church on Easter Sunday in 1967. It was an instant connection; they’ve spent every night together since they got together.

As a queer Black person, stories like these give me hope that I too can find love, be desired and wanted. Seeing the ways that these couples found their self-worth while discovering love and starting families is the fairytale ending I never see in the media landscape around me. With its message that queer people of colour have every right to love and be loved, this book is a true gift.

Prior to the book’s release this week, I was able to catch up with Jordan over the phone to discuss the heartache that led to his original article, his interview process and the importance of empathy in his work.

What inspired the initial New York Times article, and how did that lead to the book?

I had just started at the Times, and I was helping on this special section we were doing for Pride month. During that time, I was talking to this boy that I was really into, but it didn’t seem like he was into me back.

There was a really bad snowstorm, so we had a snow day from work. I was sitting at home in my feelings all day long. I remember wanting to look for images of couples of colour to make myself feel better. I was like, “I can’t find anybody; I can’t find another Black man who looks like me in love with another Black man who looks like him.” That was really hard. So, I took that energy with me into the pitch meeting for this Pride project. It wasn’t fully-formed at that point. I was like, “I want to go, want to meet couples of colour, get some inspiration from them, see what happens.”

The story hit a chord.

It went super viral online. I think it was one of the biggest drivers of traffic from Twitter to the Times that day. I remember that after that, I had so many more questions. I had people reaching out, being like, “Hey, I would love to share my story with you.” It became much bigger than I had imagined it would be. From there, I got my book deal and worked on the project, and that’s where we are today.

How did you find the couples featured in Queer Love in Color?

All over. I did a shit load of reporting—lots of being on the phone, talking to people, internet research. I published a piece in the Times, right on the advertisement page, which helped me get people to reach out. A lot of word-of-mouth.

Credit: Jamal Jordan/Queer Love in Colour

How do you use photojournalism as a tool for storytelling?

I think for me, my biggest belief is that imagery connects to people. It builds empathy in a way that text by itself really doesn’t: It gives my readers the opportunity to make eye contact, the person-to-person connection that I could get with couples in person. Also, the whole project is about seeing yourself and being seen, so the photos feel like a very integral part of that.

What advice do you have for other photojournalists who want to tell compelling stories?

I always tell people to think of the story that you would just kill to see exist and one that you feel uniquely pulled to tell. I always say, remember that, of all things, the strongest thing that photography does is help build empathy. It’s like grasping an idea—the entry point to whatever story.

Are there any queer relationships of colour you look to as a Black, gay man?

There aren’t any I can think of to look up to. Part of why I created this book is because it’s so hard to think of any queer people of colour that exist in pop culture that I can look to and say, “I’m up there.” I feel like that’s really hard.

I think when I do need inspiration, I have couples in my personal life I look to. I think of my friends, Hassan and Marquis, who lived close to me. Each of them read the original published article. I’ve always been inspired by the way that I’ve seen them build community. It was like in my own personal spaces, which was awesome to see. One thing I found while researching, in general, is that queer people of colour are able to find support in the community in ways that people from other communities can’t, and so I’ve been trying to think more about that.

Credit: Jamal Jordan/Queer Love in Color

Did working on the book provide that representation of queer love you wanted growing up?

It made me realize that, even though our community doesn’t have the visibility in pop culture that we want, we’re still a community that exists; we’re very strong all over the world. So it made me feel less alone in that way.

After hearing the same threads of stories over and over again of people who have the same struggles with self-love and learning if love will be possible for them, hearing that from so many people made me feel really grounded. Hearing so many people talk about how long these processes of finding their partners and building communities made me—as a younger person—a lot more patient about the process.

What’s one thing you hope readers take away from Queer Love in Color?

My dream is that small kids or teenagers—well, they’re all small kids to me—can look at this book and just really feel a sense that any of these people could be them, too. The first essay is called “That Could Be Me,” and that’s what I hope that people [will think when they] look at this book and see these couples.

Queer Love in Color by Jamal Jordan is published by Ten Speed Press/Penguin Random House in Canada and the U.S.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra