So just how exactly did a straight, Chilean guy end up writing and directing a Native lesbian love story set in a women’s prison?

Pose the question to filmmaker Jorge Manzano and he just laughs. “I know, I know. I guess it probably does seem kind of surprising. But to me, emotions, love, that’s universal. We all love. We all struggle. I thought it would be powerful to make a film about an impossible love and I ended up making that love between two women in jail.”

In Manzano’s feature Johnny Greyeyes, the titular character (Gail Maurice) has spent the past seven years in Kingston’s notorious Prison For Women. She’s been in custody most of her life, starting with a stint in juvenile detention as a teenager. She has a bumpy relationship with her good-hearted but wayward brother Clay and an inescapable bond to her defeated mother (Gloria May Eshkibok).

Counselling sessions with an Aboriginal therapist has helped to heal some of Johnny’s wounds, but real redemption comes in the form of Lana (Columpa C Bobb), a rebellious and compelling lifer. (“I heard the food in here was worth killing for,” she deadpans to Johnny at their first flirtatious meeting.) The pair falls in love, but when Johnny comes up for parole, Lana is devastated at the prospect of being left behind. Meanwhile, as Johnny prepares for life outside, she discovers that freedom might prove to be as painful as imprisonment.

Manzano’s script was inspired by his late friend and colleague Marcel Commanda, who had recorded a series of interviews with Native inmates in the late 1980s. The pair had worked on a short film together, City Of Dreams, but Commanda died before Manzano had completed Johnny Greyeyes.

“One thing I was struck by in reading Marcel’s interviews was the similar space the inmates were in,” Manzano says. “They all had the same backgrounds of poverty, struggle and an inability to cope with the system. They all seemed to have been on the same trajectory.

“It was from that place that I started writing the script. Because while I don’t think that prisons actually rehabilitate or heal people, it’s in prison where Johnny finally comes to terms with herself and decides to face her past. I wanted to show through Johnny the humanity and love and hope I read in those interviews.”

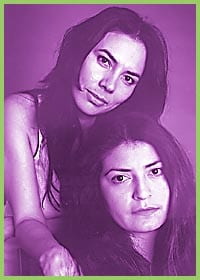

Johnny was the first major film role for Maurice, who delivers a performance that is equally as raw as it is gentle. Despite a rage that boils just below the surface, Maurice gives Johnny a heartbreaking vulnerability, especially in her scenes with Bobb and Eshkibok.

“I once had the opportunity to go inside P4W [Prison For Women] with Native elders to visit the prisoners,” she says. “Seeing those women – who are just like you and me, with similar hopes and fears and dreams – really affected me. With the role of Johnny I had the opportunity to be their voice and I prayed so hard the whole time we were filming to be an honest voice for those women.”

In the difficult role of Lana, Bobb is powerfully charismatic. “I liked having to find an active way of playing someone who was stuck,” says the seasoned actor and playwright. “She’s a lifer, she’ll never be free, but she has a need for freedom that is so desperate that she acts in ways that are, at times, mad.

“One of the great joys and challenges for an actor is playing opposing forces. Lana is all opposing forces.”

Both Maurice and Bobb drew on personal stories and experience to create their characters. “We had a man on set who had been an inmate and we asked him a lot of questions. But I think most Native people in Canada know someone who’s been in prison, or had dealings with the justice system in some way,” says Bobb, who, as a traditional Native singer, has performed in prisons and met inmates.

Echoes Maurice: “I’ve had friends and family members who’ve been in jail. And they were kind and gentle people, who through some bad choices and bad luck ended up in a bad place. What I wanted to do was show their humanity.”

Adding to the many challenges of their roles was the film’s shoestring budget and lengthy shooting period. Johnny Greyeyes took four years to complete. As a result, the actors had long hiatuses between scenes and several changes to the script during shooting.

“I always say that the difference between acting in films and acting in theatre is that film is a series of sprints and theatre is a marathon,” says Bobb. “Johnny Greyeyes was both. It was exhausting and very rewarding.”

One of the opening scenes, in which Johnny walks down the front steps of prison and heads home on a bus to see her mother, had to be shot in the fall to capture the colours of the leaves. Maurice was recovering from abdominal surgery at the time and could barely walk.

“I was so in love with the role that I would do anything just to play it,” she says. “There I was, six days after my operation, and we only had a window of a couple of days to shoot and I could barely stand upright. I’d be hunched over at the top of the stairs and I’d say to Jorge, ‘Give me a five second cue before you start shooting so that I can straighten up enough to walk.'”

The length of the shoot also meant that the relationship between Johnny and Lana grew as time went on. “I never had a moment of concern about playing a lesbian character,” says Maurice, who is a lesbian. “I was thrilled to finally have a gay role, because I’m always cast as a het. And everyone who saw early clips of the film, where the relationship between Lana and Johnny is very minor said that they wanted to see more of it. My only concern was for Columpa, who is straight. I wanted her to be comfortable.”

But Bobb’s only concern about playing a lesbian was that the role not be exploitative. “We all knew that this could not be a ‘dykes in jail’ kind of thing. The love needed to feel real. And the response from audiences has been really positive. They really liked the dignity and respect that Gail, Jorge and I brought to the relationship.”

After screening at the prestigious Sundance Festival in 2000, the film went on to play festivals around the world, including a sold-out house at the legendary Castro Theater at the San Francisco Lesbian And Gay Film Festival and the Toronto Inside Out fest, where it won best feature in 2000.

Maurice says that the Q and A sessions after screenings have been fascinating. “People are always enthusiastic, but in different places and at different kinds of festivals, different aspects of the film interest people: sometimes it’s the relationship, other times it’s the situation of Native people.

“In Berlin, some of the questions were so ignorant – but not in a cruel way, just really uninformed. I remember someone asked me how it was possible that I had left Canada. They thought Indians couldn’t leave their reserves and couldn’t have passports. They were amazed that I could travel around the world. At times like that I just hope that I can educate people a little and shatter some myths and stereotypes.”

Adds Manzano: “This film is very unique. Nothing like it has been made before. I’ve been amazed by the interest and support it has received. This is a story that hasn’t been told before and audiences really get into it. It touches them. They want to know more about these characters and the people they represent. And I think all of that is owed to how collaborative the process has been. This film is as much the actors’ as it is mine.”

JOHNNY GREYEYES opens Fri, Nov 16 at the Carlton (20 Carlton St); call (416) 598-2309.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra