One of the editors who worked on my first book asked me to make it “more universal”—which, she quickly clarified, meant “hetero.” It was a book for the mainstream after all, a work about technology and how it changes our lives. There was no need, went the argument, to gay things up. Queer elements would ostracize straight readers, or worse, make them uncomfortable. This was 2013, and the discomfort of the majority was still seen as a death knell for mainstream authors.

So, I acquiesced. My husband—boyfriend at the time—would still appear in those pages, but the tone was sanded down, and several scenes were deleted. What amazes me looking back at this moment a decade later (on the eve of my third book’s publication) is how used I was to the request, how sensible it seemed.

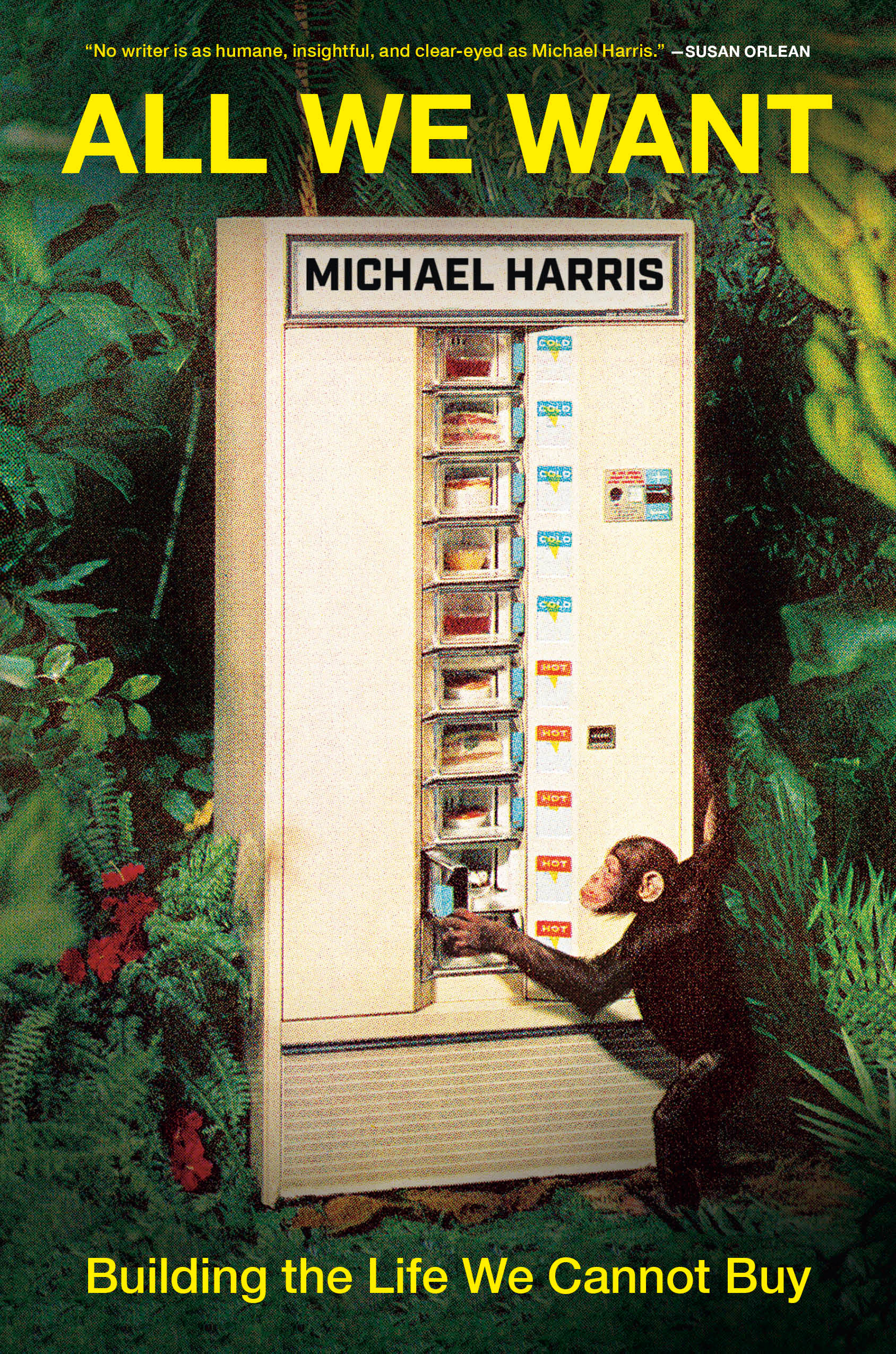

Credit: Courtesy of Penguin Random House

When I began my professional writing life, in 2002, I had no sense that my gayness and a mainstream career were incompatible. In fact, when I started out, I would write explicitly queer articles for indie publications (including this one) and then write buttoned-up reviews for the Vancouver Sun the next day. I was made of more than one persona and it felt only right that my work wandered into more than one world. Before long, however, those worlds collided. A Sun executive learned there was a “pornographer” in their midst and I was dismissed; my “dirty” writing cost me my main source of income.

And so, by the time that book editor asked me to de-gay my writing for a mainstream audience, I wasn’t surprised at all. Smut, I had learned, must stay in the smut box. If you want to play with the big boys and learn to write “universally,” then you must guard against perversion. Yes, there was room for queer books, but their subject had to be, explicitly, queer identity. Queer narration in a book about birds, say, would be unmarketable to nine-tenths of bird fanciers. Queer narration in a book about the Second World War would be unmarketable to nine-tenths of history buffs. This paranoia—this fear that an openly queer narrator could not discuss so-called mainstream subjects for a mainstream audience—was rampant until very recently at the major publishing houses. As one author recently told me: “Publishers in New York have been making overly conservative, cartoonish guesses about what Middle America can handle.” Consequently, queer authors who happen to be fascinated by non-queer subjects have been subtly closeted.

Why does this matter? If these authors are not writing about themselves, why should we care whether they’re openly writing as themselves? I only began seriously asking myself this question when, at a recent event, an audience member asked, “Why do you always talk about your husband in your books, when your books aren’t actually about gay things?” I began to wonder: What is a gay book? And are queer writers of non-fiction really, still, expected to denude themselves of their ambient sexuality? Is offhand queerness still discomfiting for the mainstream reader? And, most importantly: Do I give a fuck?

“Are queer writers of non-fiction really, still, expected to denude themselves of their ambient sexuality?”

It’s hard to remember, but until very recently, venturing outside the bubble of “identity literature” was a genuinely fraught adventure for queer non-fiction authors. The nature writer Robert Moor, author of the acclaimed On Trails: An Exploration, began his journalism career a little more than a decade ago and, because his reporting took him to remote, conservative locations, Moor felt he had to stay closeted in order to be taken seriously. He would refer to his boyfriend as “my travelling companion” with Victorian tact. The decision wasn’t merely prudish, though. “If I’m reporting in a highly repressive country,” he told me, “they could Google me and throw me in jail.” Reporting in Papua, Indonesia, for instance, he and his husband, Remi Morawski, went into the jungle to visit the Korowai tribe—but Moor knew that, in Papua, their homosexuality could make reporting impossible. “We came up with a whole backstory, including fake wives to explain our wedding rings. We quizzed each other about our wives. But then when the time finally came and someone asked Remi point-blank about his wife, he couldn’t bring himself to lie, so he pretended to hear me calling his name from another room and just walked away.”

Though Moor is still not always out when reporting, he is always out in his writing. “I realized, if you’re going to write a book about nature, your sexuality is relevant. It informs your views of what is natural or not. My sexuality is a lens.” Our mainstream literature is only just recognizing the value of such lenses in arenas traditionally hostile to queerness. Think of what’s been lost when so-called mainstream writers who are trans or lesbian or gay felt they couldn’t include their whole selves when writing about science, sports or anything at all in the world.

Neurologist Oliver Sacks (author of Awakenings and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat) gave us some of the most extraordinary descriptions of the human mind—including insights that were doubtless informed by his queerness—and yet Sacks didn’t come out in his writing until 2015, at the age of 82. He died that same year. Here was a writer exquisitely equipped to illuminate the subtlest crannies of our personalities, but his work was also stymied by self-censorship and fear. (When Sacks came out to his mother she called him an abomination and wished he’d never been born.)

The legendary writer Bruce Chatwin remade the genre of travel writing, and yet was closeted his whole life, even as he lay dying from AIDS-related illness in 1989, at the age of 48. Was there, perhaps, even more that he could have told us about the human experience had he felt more free to be himself? Some will argue that his repression was, in fact, a source of insight: the theme of exile and the status of outsiders runs throughout his work, for example, and perhaps he wouldn’t have been drawn to such elements if he’d felt more comfortable in his own skin. Perhaps. But muzzled voices are not all we have to offer. We can only guess how much richer his tales from Patagonia or Australia or Wales may have been had they included a fuller portrait of the narrator.

(The whiteness and maleness of these examples, by the way, is not an accident. Proximity to privilege is the game itself. Authors like these were tempted into mainstream literature precisely because they could pass as bonafide members of a traditional literati.)

“Think of what’s been lost when so-called mainstream writers who are trans or lesbian or gay felt they couldn’t include their whole selves when writing.”

In remembering what’s been deleted we can also look forward to what fantastic work is yet to be published. As Moor reminded me, the field of queer ecology has already begun to bloom—complete with fabulous new readings of “the natural” and “the unnatural.” But every single subject will soon be ransacked by queer authors employing their own fresh analysis, and these queer readings and writings will be delivered to the general public by publishers who cannot even remember a time when they second-guessed themselves.

As for me and my latest book, the husband is very much there this time. It’s a book about the story of consumer culture and our search for a new story that might replace that old, untenable tale. It’s not a “gay book,” but I cannot imagine it without my gay love baked into it. The ideas are half my husband’s; the spirit of the book’s final chapter derives entirely from his experience, not my own. Most writers of non-fiction are, I think, observers first: we watch the world, trying to understand an objective reality. And yet every observation, every insight, is only made meaningful when it filters through that particular prism of personality and subjectivity that is specific to us, to our specific hearts. And so, what a relief it is now, what a great thing, to say that while working on this new book nobody questioned my husband’s presence—it was blissfully taken for granted. Of course the husband stays in the book. There would be no book without him.

Michael Harris is an award-winning author whose latest book, ALL WE WANT: Building the Life We Cannot Buy, is on sale now.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra