Roaming, the latest graphic novel by collaborators and cousins Jillian and Mariko Tamaki, opens cinematically, with a dramatic fakeout. Urgent bubbles of dialogue lead us across the first four pages. Someone is ordering an unseen person named Marlene not to spill the secret that’s about to be divulged. We flip the page, eager to get the dirt, but instead, the next panels zoom out to reveal that the speaker is just a stranger in the Newark airport, where one of our protagonists, Zoe, clad in the traditional all-black garb of new queerness, is rubbing her eyes, fresh off a flight and waiting to reunite with her high school bestie, Dani. We never find out what the stranger’s secret was, but as we move into the story of Zoe and Dani’s trip to New York, Zoe moves from overhearing someone else’s drama to being caught in the centre of a stormy trio of personalities and needing to manage her own turmoil.

It’s Spring Break 2009, and Zoe and Dani, who now attend university in different Canadian cities, are taking a long-awaited trip across the border together at the tail end of their first year away from home and one another. Meeting up for five days in New York is the perfect way for them to reconnect as new adults, but also a perfect setting for the relational turmoil that can bubble up in that transitional period from teenhood to young adulthood, especially in the pressure cooker of a group trip.

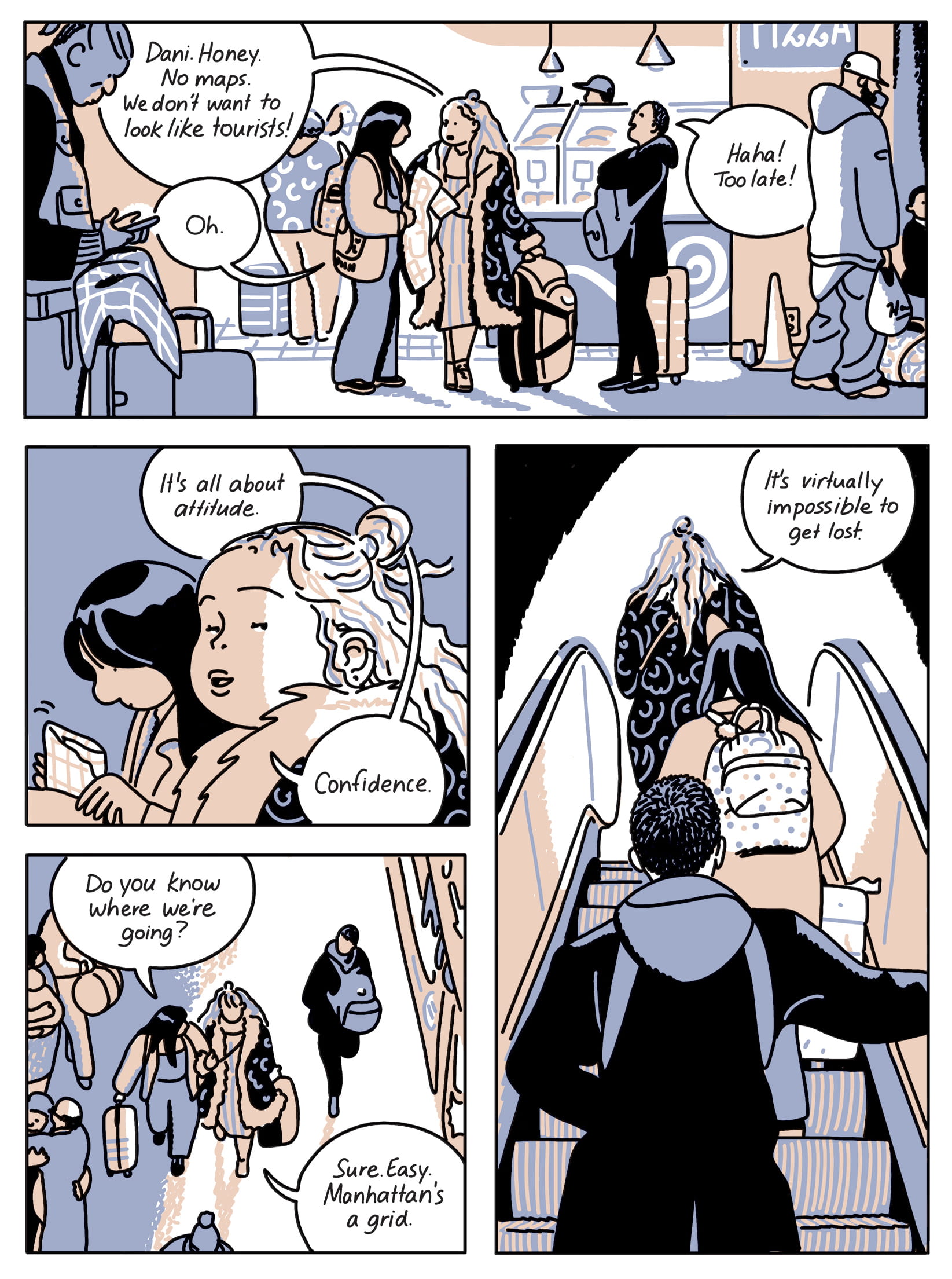

Credit: From “Roaming,” copyright Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki, courtesy Drawn & Quarterly

Mariko and Jillian Tamaki know the ups and downs of travelling with someone you’re close to. They have been creating queer graphic novels together for nearly two decades, and touring together for nearly as long. Their first two collaborations featured Mariko’s writing and Jillian’s illustrations. The cousins published Skim with Groundwood Books in 2005, back when much of the graphic novel scene was dominated by white men. Many of the prominent graphic novelists of that era focused on a certain type of white nerd alienation, usually, though not always, featuring male protagonists—think Seth (Palookaville), Chris Ware (Jimmy Corrigan), Charles Burns (Black Hole) or Daniel Clowes (Ghost World). There were of course some exceptions—Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home was published in 2006, and there were artists like Adrian Tomine (Shortcomings), Julie Doucet (Dirty Plotte) and Marjane Satrapi (Persepolis), who were all offering alternative viewpoints. But it was certainly unusual for a literary graphic novel to be created by two women, both Asian Canadian, or to focus on a teenaged Asian goth girl navigating queerness in high school.

Jillian and Mariko created the first iteration of Skim as a 24-page floppy comic published in Kiss Machine, an early-aughts feminist zine out of Toronto. When the full-length graphic novel came out, it was a surprise hit. “We didn’t really know how to make a comic when we were starting out,” Jillian tells me over Zoom, when I interview her and Mariko—Jillian calling in from Toronto and Mariko from LA. “There weren’t any classes on comics back then, not like there are now, so it was really about me bringing my design training and Mariko bringing her experience in theatre, and us intuitively crafting the process together, sort of like a screenplay and sort of like a magazine layout.”

Their intuitive working methods paid off: Skim was a nominee and winner of various awards, and launched both cousins’ careers. “We both seized that moment, which was very pivotal in both of our careers,” Mariko recalls, “and then we each went off and did our own thing for a while.” Both Mariko and Jillian have published other graphic novels, either alone (Jillian’s SuperMutant Magic Academy and Boundless) or with other collaborators (Mariko co-created Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me with illustrator Rosemary Valero-O’Connell, and writes for both Marvel and DC Comics). Jillian is a renowned commercial illustrator, with frequent contributions to the New Yorker and the New York Times.

The cousins teamed up again for another successful graphic novel in 2014, This One Summer, a thoughtful tale of two preteen cousins who are both repelled and fascinated by the behaviour of the adults around them, which they witness one summer in Ontario cottage country. Its dedication to portraying the complex lives of preteens and teens also resulted in widespread bans across the U.S. It was named the most challenged book of 2016 by the American Library Association, for its inclusion of LGBTQ2S+ characters, drug use and profanity, and for being considered sexually explicit with mature themes.

Published by Drawn and Quarterly, Roaming, which Jillian and Mariko created during the early stages of the pandemic, leaves behind the worlds of preteens and teens, parental oversight and high school for the wilds of new adulthood. Unlike the more delineated working method that they used for Skim and This One Summer, Roaming was formed through an organic process of passing the script and Jillian’s illustrations back and forth, the two cousins developing the storyline together, layer by layer, until it was finished. The story finds Zoe and Dani excited to reconnect—but things get messy quickly. The catalyst for the turmoil is a third character, Fiona. Dani, the more earnest and wide-eyed of the two friends, has brought along her new art school friend, whom she introduces to Zoe as “CRAZY talented” and who gives off a practised air of worldly ennui. Fiona is drawn as a whirlwind of energy. Her big blond hair and exaggerated gestures fill every frame she’s in. Fiona casually but repeatedly mentions her older brother, whom she has visited in New York many times; she dismisses L.A. as “basically a dead place” and declares that they will not use paper maps in public. “We don’t want to look like tourists!” She quickly charms Zoe, and just as quickly works to drive a subtle wedge between the two BFFs. “You don’t seem alike at all!” she tells Zoe, who is more reserved than Dani, and more self-deprecating.

Despite her posturing, Fiona is perceptive—she’s the one who names Zoe’s queerness. While Dani peruses the art at the Met, Fiona tells Zoe, “You have that cool dyke thing going on.” Zoe, with her protective hoodie and newly buzzed head, balks at the phrase. But she acquiesces: “I don’t like that word. But yes.” This is a quiet moment, the two girls up in a balcony, looking down on a gallery of sculptures of the Buddha (“a real monument to Western imperialism,” Fiona asserts dismissively, the oh-so-worldly white girl educating the two Asians); but it’s also a defining one. “It’s about the first time somebody finds you sexy,” Jillian says, “about when you’ve changed yourself, your self-expression, and someone appreciates that and desires you.”

That first thrill of queer recognition can be intoxicating—it doesn’t take long for Zoe to hook up with Fiona, who’s been flirting with her more and more obviously and, true to her assertive character, initiates the whole thing. The two have sex in the bottom bunk, in their shared dorm room with Dani, who of course overhears. Drama! The trio quickly unravels after this, fracturing across Jillian’s propulsively drawn panels. All three try to figure themselves out—sometimes moving through the expansive chaos of Manhattan, sometimes trapped in the cramped container of their shared hostel room.

The book’s title functions on more than one level: the characters are roaming free through a major city, on their first trip as autonomous adults, and they are also limited by the technology of 2009, the expense and unreliability of cell service on Canadian phones in the U.S. “Should I turn on roaming?” was an agonizing question during international travel back then. “Will it cost a million dollars to send a text?” When Dani goes off on her own to get away from Zoe and Fiona’s horny romance, she is unreachable. Worried about her friend and wracked with guilt, Zoe still gripes about the cost of turning on roaming in order to contact her. “Yes. The entire economy will collapse again if you make a phone call,” Fiona tells her, exasperated. Is Zoe unwilling to spend the money on roaming fees, or is she, perhaps, a little bit avoidant? “I think you can’t stand someone being mad at you,” Fiona throws the jab over her shoulder, and, for all her posturing, she may be right.

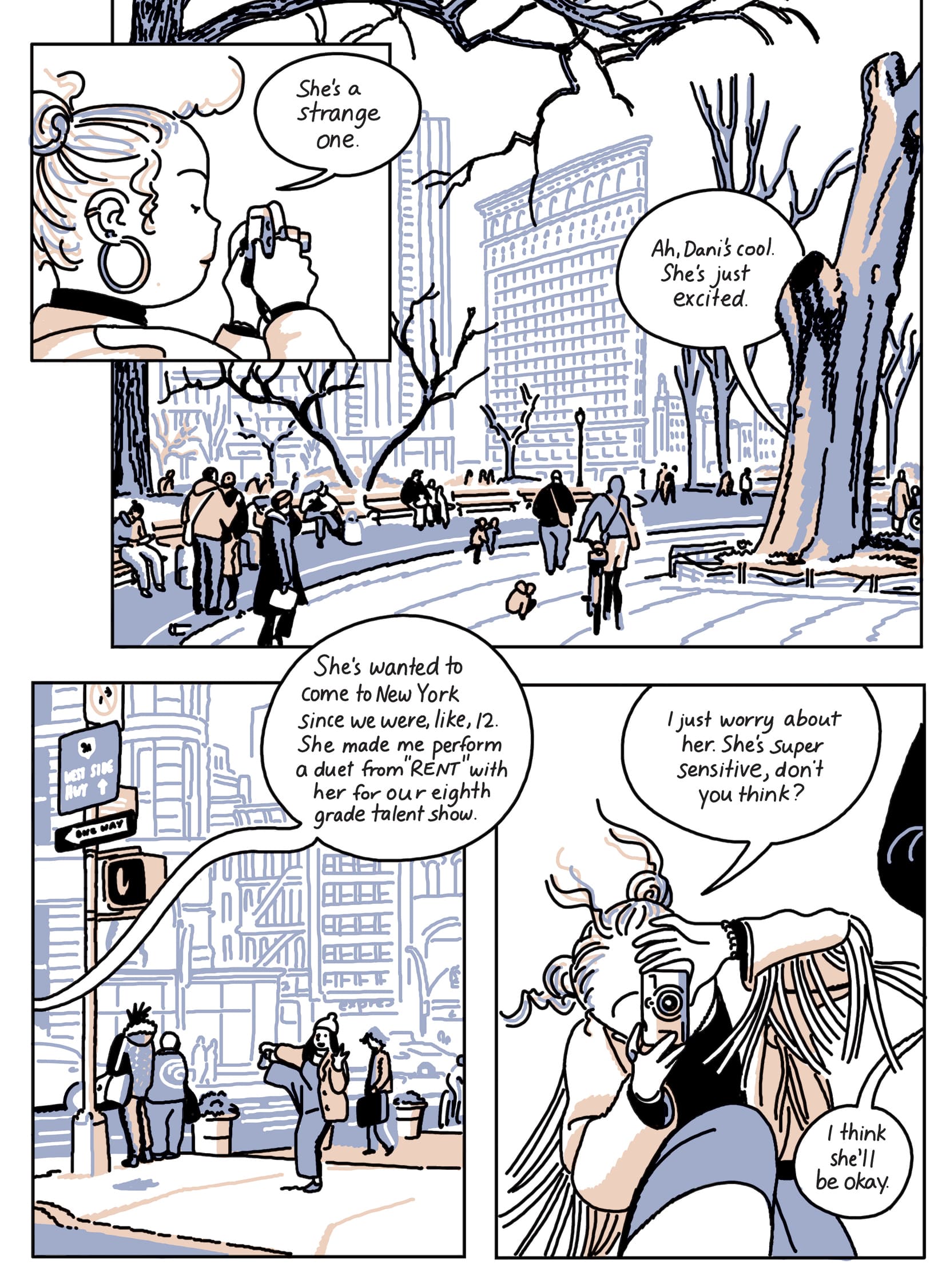

Credit: From “Roaming,” copyright Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki, courtesy Drawn & Quarterly

“The story is about having some, but not completely great, communication with your friends at that age,” Mariko says. “You have some ways of talking to each other, but not a completely unmarred way of communicating.” Zoe can’t speak directly to Dani about her newfound queerness and her fling with Fiona, and Dani struggles to confront Zoe about how left out she feels in the trio. They are, to some extent, dragging their high school selves around with them; they struggle to cast off the high school selves they’ve outgrown, while trying to hold on to their close friendship. The cell service is patchy, and so is each character’s ability to be direct or vulnerable with the others. Fiona gives off an air of confidence—she impresses the other two by telling a smarmy man at a bar to fuck off, but when faced with Zoe’s loyalty to Dani, she goes rogue. Fiona goes after what she wants, impatient with both Zoe and Dani for being more tentative with their desires, but she is unable to express her own uncertainties and fears.

Mariko and Jillian set Roaming over five days in 2009 for reasons of both nostalgia and technology. In 2009, smartphones existed, but most cellphone users still had flip phones. The cousins were more interested in portraying an era in which our lives were less moderated by phones and the internet. The year 2009 is now distant enough that we can have some perspective on it, Mariko says, yet it’s deeply familiar to both of them, because they were young adults then, an age that makes you porous and absorbent, when everything that happens takes on epic proportions.

Both emphasize that the story is not autobiographical, however. They feel that there is often an assumption that everything written by non-white or non-straight authors is memoir to some extent, unless it’s very obviously in the fantasy realm. “There are autobiographical moments in the book,” Mariko says, “like when Dani is nervously sipping a shot of whiskey, while her friends are throwing theirs back, that is the most call-out autobiographical moment of any book ever to me, personally!” But this particular story and these particular characters are the result of the cousins’ collaborative imagination. “Typically, when you’re writing fiction, you’re immersed in that world alone, that theoretical little universe you’ve built,” Jillian says. “So, it is interesting to have a writing partner that you’re actively crafting the universe with. You get to gossip about your characters as if they were real people.”

Dani, Zoe and Fiona feel incredibly real—just like the characters in Skim and This One Summer do. There is an effortlessness to the dialogue, to the way the three girls’ bodies move through the panels on each page. Every scene feels lived in—the trio’s dramatics are foregrounded against the overwhelming bustle of downtown Manhattan, their shifting dynamics and peaking emotions even more poignant as the three of them are dwarfed by crowds, buildings and congestion. Writing and drawing queer Asian characters was never “strategic” for the cousins, Jillian says. It’s just what comes out when either of them approaches storytelling. “And now these questions of representation are a much bigger conversation in the publishing industry, of course,” Jillian says, “but I just try to block that stuff out. You can’t think about that stuff while you’re working, because you’ll get tripped up.”

Mariko says that while people often expect her to name her Japanese influences, because she is half-Japanese (Mariko and Jillian’s shared paternal great-grandparents emigrated from Japan), she feels artistically more influenced by (white) Canadian literary giants like Alice Munro, Margaret Atwood and Timothy Findley. “I think my writing ethos comes from more of an Alice Munro place. There is something about the very detailed perspective on the world of each book that she wrote, the specificity of each character, that compels me. Her writing is infused with identity, but not in the way people think about it now.” Mariko and Jillian’s storytelling approach is to write character-driven work that naturally takes cues from experiences that one or both of them have had. Jillian adds, jokingly, “Yeah, our books are flavoured with identity—Naturally Flavoured with Identity!”

An aspect of Roaming that Jillian did have to be particularly intentional about was the visual representation of New York City in 2009. Originally, she meant to travel back there (she lived in New York from 2005 to 2015), to take reference photos to draw from. But then came the COVID-19 lockdowns. She had to get creative. The acknowledgments thank “the users of Flickr and their documentation of New York City in 2009.” Jillian pored over photos of every nook and cranny of Manhattan, including its various tourist traps, intent on documenting that particular era in that particular place in devoted detail. The thing with New York is that you can’t get away with drawing it wrong—New Yorkers will notice! She went as far as ensuring that she always drew the traffic going in the correct direction on the correct street. “I really had to have a local’s knowledge and analysis, a local’s attention to detail,” she says. “However, because of the characters in the book being from out of town, I had to also draw New York through the emotional lens of a tourist.” The result is a highly textured narrative, both visually and relationally, which allows the reader to get almost uncomfortably close to its three characters, while also maintaining a wondrous appreciation for the wider world that holds them.

The beauty of Roaming is that it captures its characters at a potent moment of change, one that holds possibilities and that also contains loss. Until now, the Tamakis’ books have been about kids and teens looking to the future, whereas with this project, they portray young adults who are beginning to look backward, to understand that certain important things get lost as you get older, that passing into adulthood is “passing through a doorway,” as Mariko puts it. Both seem to sense that they are passing through a kind of doorway with this work, as well. Jillian has moved away from brushwork and toward cleaner lines. She’s now spending time in her studio, experimenting, without “a hard and fast destination” for the first time in years. Jillian and Mariko may lose some of their old audience along the way, Jillian says, as her artwork changes, and as they both move away from telling stories that fit the YA category, but they are willing to relinquish that kind of control. Like friendships, art can’t remain static.

Mariko and Jillian Tamaki are heading off on an extensive book tour with Roaming beginning Sep. 7 in Washington, D.C. and ending in L.A. on Oct. 21. The Toronto stop is Sep. 14.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra