Ballet star Rex Harrington was intrigued when receiving the Order Of Canada last month; the principal dancer at the National Ballet Of Canada was inducted into the Order along with leaders from fields like medicine, the arts, politics and sports.

“I went up to Frank Mahovlich to shake his hand,” says Harrington, “And he knew who I was.”

When a hockey legend recognizes a gay dancer, you know things have changed in this country.

The National Ballet Of Canada started 50 years ago – Nov 12, 1951 to be exact – as a rag tag group of artists and promoters, with famed Royal Ballet dancer Celia Franca at the helm.

Toronto in 1951: The city stopped at Eglinton Ave, the 401 was surrounded by corn fields; there was hardly any homegrown theatre, culture meant the Maple Leafs (who won the Stanley Cup for the seventh time that year; Mahovlich would join the team in ’58).

From the outset, the National has been a home to out gay men – and many more, besides – on stage, behind the scenes and in the audience.

The current artistic director James Kudelka is one in a long line of highly talented gay men at the creative helm of the company. The list includes such luminaries as Alexander Grant, Rudolf Nureyev, Erik Bruhn, Glen Tetley and Reid Anderson.

In 1966, a 10-year-old Kudelka enrolled in the National Ballet School. He once described himself as “an ultra-serious child who wore fishbowl glasses and carried a briefcase.” Performing in the kids’ corps, Kudelka was awe struck. “It was overwhelming. I was in the same dressing room as Earl Kraul – and he was a star to me. The year before I was watching him from the back row of the Royal Alex.”

As a youngster, Kudelka paid close attention to rumours of who was gay and which pair was a couple. It was a heady mix: Being away from home in a boarding school – and all the adolescent experimentation that implies – a punishing physical regimen, working towards a career, dealing with his sexuality. Those early days evoke bittersweet memories. The National was a safe home for Kudelka’s sexual awakening, but it was also where he learned the “covertness of homosexuality” at that moment in history.

“You learned both sides at the same time.”

Kudelka says that during the late ’60s, Celia Franca was intent on clearing out the growing homosexual presence in the company. He jokes that his arrival threw a wrench into the works. The start of Kudelka’s career coincided with the most glamorous period in the company’s history, full of gay dramatics.

During the ’60s, the company was mounting increasingly demanding works and the highly respected Danish dancer Eric Bruhn was a frequent guest. His lover was Rudolph Nureyev, the Tatar Russian defector who was electrifying audiences in the West.

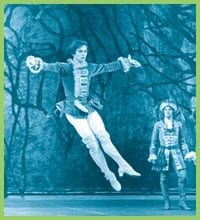

Nureyev’s sexual aura took men and women’s breath away and transformed the image of the male dancer. His beauty changed ballet. Gone were the effete gentleman dancers, in strutted animal passion.

Everyone, it seems, has slept with Nureyev; his sexual exploits are legion. He said he couldn’t go more than a few hours without sex. Once, he was caught having sex in a washroom around the corner from a theatre – during a performance.

“He never made a move on me. He preferred more cowboy types, ” says Kudelka, wistfully. During the 1972 tour, “Nureyev barged into a change room yelling, ‘Who has the tightest asshole?’ I think I said I probably did since I was only 16.

“I remember a later gala in Toronto, and he kissed me full on the lips. I can still conjure up that kiss; I’ll never forget it.

“Nureyev was like a bell; he just rang.”

The dance star made frequent visits to Toronto to be with Bruhn during the ’60s, and was even arrested in 1963 for dancing down Yonge St (where most of the city’s gay bars were then located). In 1965, when Bruhn mounted his version of La Sylphide on the National, Nureyev gave Toronto audiences a surprise performance, replacing an injured Bruhn at the last moment.

In 1972 – the same year Kudelka started dancing with the company – Nureyev and promoter Sol Hurok, picked the National to mount Nureyev’s lavish version of Sleeping Beauty. The mammoth 21-city tour culminated with the company’s first-ever performance at the Met. The influential New York critics fell in love.

Nureyev launched the National as an internationally respected company, and he launched the company’s first home-grown stars, Karen Kain and Frank Augustyn.

“Nureyev became very fond of us and we became a home for him,” says Kudelka.

There was a qualitative difference to the company; they had talent and they could cause a buzz. “I think it really sunk in when we went to England with Nureyev and he invited us to his London home. Then we threw a party for him at Sardis and people like Andy Warhol came.”

Harrington, a Peterborough native, started with the company towards the end of that tumultuous period. “My mother enrolled me in the National Ballet School because she knew before I did that I was a little bit tipped.”

Like Kudelka, the ballet school was almost too intense for Harrington. “A boarding school for ballet dancers was a bit much. I had to be away from the school to deal with my sexuality.

“I was a afraid of the flaming queens who’d come to the school,” says the now flamboyant dancer.

Harrington started performing with the company in 1983, the year Bruhn took over as artistic director. Harrington says that Bruhn was had the greatest influence on him. “He was a role model as a dancer and as a gay man: beautiful, strong, with a deep voice, his sense of style and his intense personality.”

Bruhn died in 1986, officially of cancer, though some assume the cause was AIDS. His untimely death was a terrible blow to the company, and the blows would keep coming. Harrington would need character to keep dancing in the ’80s and ’90s while so many of his colleagues – here and in the US – died of AIDS, including his lover soloist Gregory Osborne who died in 1994. Nureyev died of AIDS in 1993.

But there is a new generation of dancers, whose experience of AIDS and homophobia is totally different from their predecessors.

In his fifth year as artistic director, Kudelka says he’s somewhat bewildered by the latest generation, where teen dating has entered the gay lexicon. “It’s so much more free, now.

“But I’m of a certain generation. Freedom has taken away the frisson of gay sexuality. What we were pushing up against was fun to push up against.”

Harrington, meanwhile, looks at the next wave of dancers with excitement and concern.

He sees a large block of younger dancers with talent rising through the ranks. But he worries that they won’t have the opportunities he and others have had. “We used to be a real national company, always touring east and west and internationally. Cutbacks have meant the younger dancers don’t get the same learning opportunities we got.”

He hopes he can impart a sense of history to the dancers and he gets a real charge from the occasional master class he conducts, something he’s looking to do more of. He laughs. “Oh God, maybe I’m turning into one of the flaming queens who scares the youngsters!”

The mixed program opening Wed, Nov 7 offers a quick sampling across history: George Balanchine’s Mozartiana from 1981, Kudelka’s highly praised Pastorale from 1990 and Kenneth MacMillan’s Solitare, first performed by the National in 1965. To celebrate the company’s anniversary, there are numerous special events scheduled during that following weekend.

Mozartiana, Pastorale and Solitaire.

$26-$110. Wed, Nov 7-11.

Hummingbird Centre.

1 Front St E.

(416) 345-9595.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra