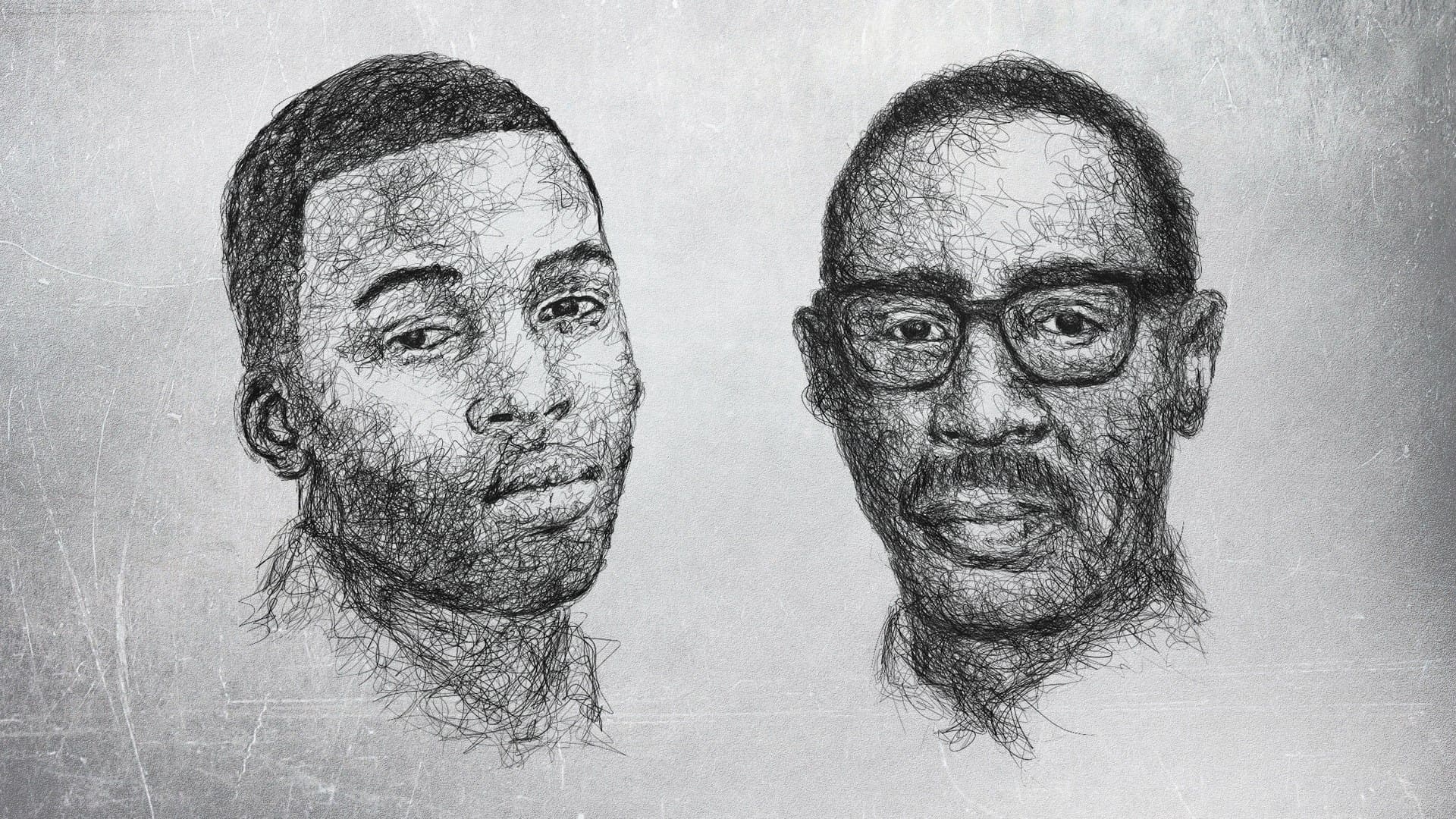

On April 14, 2022, Los Angeles political donor Ed Buck was sentenced to 30 years in prison for drug and sex crimes that included the murder of 26-year-old Gemmel Moore and 55-year-old Timothy Dean between 2017 and 2019.

The case shocked the nation, with Buck, 68, having served as a donor to a variety of political campaigns in the ’90s, as well as being a then well-respected advocate for LGBTQ2S+ issues. To the friends and families of the two gay Black men who died at Buck’s residence after he force-fed them lethal doses of methamphetamine, their deaths at Buck’s hands came as no surprise. A notorious presence among the most disenfranchised members of Los Angeles’s queer and trans community, Buck had a reputation for preying on the young and socially disadvantaged. And his history of racism, drug addiction and sexual abuse was well documented.

For L.A.-based filmmaker Michiel Thomas, this discrepancy was particularly important when it came to producing Gemmel & Tim, a documentary about Buck’s victims, which premiered at Outfest LA 2021, and is now available to rent on VOD. The film chronicles the pain and anger of their loved ones whose fight for justice initially fell on deaf ears thanks to the Los Angeles Police Department’s initial refusal to take their murder accusations seriously. Following the first death in 2017, a grassroots movement led by journalist Jasmyne Cannick, and Jerome Kitchen, an activist and close friend of Gemmel’s, arose in an attempt to get justice for the victim. However, Buck was not arrested until September 2019—eight months after Tim’s death.

“Ed Buck was the ‘political donor.’ The ‘activist.’ The ‘animal rights [activist].’ They were listing all the great things that he did, but they never talked about his felonies that he already had, throughout his life,” Thomas told Xtra over a Zoom interview. “But Gemmel and Tim were always painted as ‘escorts’… it was always [about] putting them in a box, like they deserved what was coming their way.”

The documentary differs from other true crime media in that it focuses in large part on the vibrant LGBTQ2S+ community Gemmel and Tim were a part of before their deaths, rather than Buck himself. With expert weaving of newsreel footage, camera recordings of the late victims and beautiful 2D-animated sequences, the film also includes personal testimonies showing how Buck’s heinous crimes affected queer Black and brown men, who were left feeling vulnerable as public officials refused to take the accusations seriously.

The film’s focus on real and found family is powerful, particularly in the current moment of an uptick in anti-LGBTQ2S+ legislation and rampant homophobic rhetoric from politicians in the United States. Gemmel and Tim are characterized through vibrant testimonies told by their found families—fellow queer and trans folks of colour who could easily have been another one of Buck’s targets. In the case of Tim, many of these were friends with whom he’d formed a hiking group, and teammates from the Gay Basketball League (GBL) he’d joined after moving to L.A. from his native Florida.

“Tim—he came [to practice meets] and he played his butt off,” fellow GBL member Mark recalls in the film.

“Let me just tell you what his nickname was: TMD. ‘Too Much Drama.’ That was his name on the court,” DeMarco, another friend and teammate, chuckles afterward.

This humanizes the victims and highlights how queer and trans people of colour are often victims of violence—despite conservative lawmakers constantly trying to prove otherwise. Gemmel & Tim highlights how both victims had been incessantly pursued by Buck before they agreed to provide him with company and sexual gratification in exchange for much-needed money. (Gemmel had lost his job at the time, and Tim had expenses like his grandmother’s senior citizen home bills to take care of.) It was through his visits to Buck’s apartment that Gemmel became addicted to methamphetamine, and Buck refused to let him quit.

In one of the film’s most heartbreaking scenes, a page out of Gemmel’s diary is read aloud by his loved ones:

“Ed Buck is the one to thank/ he gave me my first injection of crystal meth. I ended up back at Buck’s house again and got manipulated. I was forced to do 4 during a two-day period,” the entry read.

Having also been battling an addiction at the time, Kitchen lamented the fact that Gemmel suffered in silence.

“That’s one of my biggest regrets, ’cause I feel like we could have both helped each other out,” he says in the film. “I feel like maybe if I would have been able to be candid and transparent with what I was going through, he would have felt comfortable enough or okay enough to tell me what he was going through.”

“I knew he was escorting. I encouraged him to be safe and cautious and protect himself. Being a gay Black man in this day and age, you are already, you know, at odds,” says Gemmel’s close friend, Gia, who formed a part of the city’s ballroom scene along with Gemmel and Kitchen.

Finding subjects who were willing to be vulnerable was not a challenge for Thomas, although he tells Xtra it was a priority from the beginning. Getting ahold of Tim’s friends proved to be easiest for the Belgian filmmaker who is also a part of L.A.’s GBL, and had friends in common as a result, though the two did not know one another personally.

“To me, it was also very important to surround myself with people who had a connection to the story,” he says.

“When I approached them, I wanted to tell a social justice story … one of their biggest frustrations is that the press and the media wrote so many articles, so many sensationalized articles, but never really gave the time to paint a full picture of Gemmel and Tim. They were more than victims of Ed Buck—you gotta tell a fuller story. And that’s what I wanted to clarify from the beginning—to humanize their stories.”

Having screened in Toronto’s Rendezvous with Madness earlier this month, Gemmel & Tim is now completing its festival circuit in Vienna. The film is available to buy or rent on Google Play, Apple TV+, iTunes, Prime Video and YouTube.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra