In a summer most notable for its box office slump – if you blinked, you missed the release of Michael Bay’s budget-buster The Island – CRAZY, a gay, coming-of-age fantasia from Quebec, has become the film story of the season. Made for $7-million – most of it spent on the music rights for a killer soundtrack that features Patsy Cline, Charles Aznavour, David Bowie and Pink Floyd – it’s almost recouped that in Quebec alone, a stunning achievement for a province of only 7.5-million people.

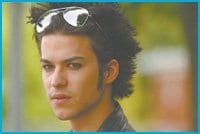

It’s easy to see why CRAZY is striking a chord. Set in politically and socially turbulent 1960s and ’70s Quebec, the film stars a beautifully pouty Marc-André Grondin as Zac, the fourth of five boys (the initials of their first names spell out CRAZY) growing up in a blue-collar, Catholic family.

Even before doll-loving, jewellery-wearing Zac understands what a “fif” (fag) is, he prays he won’t become one. He hates the thought of disappointing his dashing, macho father Gervais (played with élan by Québécois film icon Michel Côté) and his doting, eccentric mother Laurianne (a lovely, doe-eyed Danielle Proulx), who believes Zac has been given a divine power to heal the sick.

Director Jean-Marc Vallée (Liste Noire) elevates what could be just another coming-out film to a powerful family epic with a winning script co-authored with François Boulay (it’s loosely based on Boulay’s own childhood) and a sumptuously tacky, period-perfect design by Patrice Vermette.

Vallée brings the family’s messy human contradictions and complexities vividly to life – from one brother’s juvenile fartiness and another’s troubling self-destruction to Gervais’ fear of a world he no longer understands and Laurianne’s protective symbiosis with Zac.

As a child, Zac is played by Vallée’s own son Émile with wonderful guilelessness and intelligence. There’s a terrifying – and beautifully shot – scene of Zac dealing with bed-wetting at a sleep-away camp that will give every former child misfit nightmares. As a young adult, Grondin makes Zac a glam rock outcast who trades Jesus for Bowie, imbuing him with just enough rage, arrogance and selfishness to make him real.

Vallée gets bogged down in heavy-handed religious metaphors in an almost laughable sequence in which Zac gets lost while wandering in the desert after bedding a Jesus look-alike in Jerusalem, otherwise he has an light touch. He delights in composition and contrast. In one powerful scene, Gervais is in the foreground with headphones on, listening to his beloved Patsy Cline, oblivious to Laurianne behind him collapsing into grief as she receives bad news over the phone. It’s a perfect image for the film: Even people who love deeply can’t always understand, or even see, each other’s pain.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra