Credit: Gerry Donkersgoed

Credit: Gerry Donkersgoed

Credit: Gerry Donkersgoed

Best to begin with full disclosure. Joseph Couture and I were friends in the mid-1990s. There was a falling out subsequently, the details of which are trivial and not worth going into. We are now gently estranged — not enemies, but we rarely speak. I am mentioned many times in his e-book, and rarely positively (he acknowledges my writing skills but finds me naive, egotistical and a little crazy. However, I can’t claim to be singled out for contumely — Couture has little good to say about the gay community in general or about most of his one-time friends, acquaintances and colleagues). To complicate matters further, I am also at work on a memoir, one section of which covers much the same territory as Couture’s, and cynics might suspect that I intend to sink his book in hopes of buoying my own.

Still, it has to be said: I Had a Dream is badly written. The prose is pedestrian, limping from one newspaper-style sentence to another. Ordinary conversations of little import are scrupulously recorded. There are more anecdotes than one could possibly want about smoking at school. The book contains historically important material, but historians will be truly frustrated — Couture provides only one calendar date, and that not until Chapter 34. Most of the time, the reader can’t tell whether the events were happening last year or many decades ago.

And yet, it also has to be said, the book is an important document covering a now almost forgotten instance of crusading gay journalism at its finest: the work Couture initiated to uncover the biggest story ever to come out of his hometown of London, Ontario — police chief Julian Fantino’s staged-for-the-media investigation into a charade the police were calling a kiddie porn ring (it wasn’t; with Couture’s help, I would write a major piece for The Globe and Mail, exposing Project Guardian as a police assault on street youth and teen prostitution). Couture’s work is all the more remarkable because he didn’t have an easy time of it. A smart boy from a working-class family, he developed severe psychological problems that manifested both in physical pain and in the absolute certainty that he was ugly (in fact, he was cute, blond and boyish). To keep himself functional, he depended on a daily regimen of a strong psychotropic drug with worrisome side effects. He considered suicide during the period we were close. He may have been poor white trash and he may have been a psychological mess, but the work he did in his early 20s on the London story bested that of every professional journalist in the country.

How that happened provides the only reason to read this book. Couture won’t like that assessment. He sees I Had a Dream as the record of an inspirational journey: from the belief that his journalistic and political work could change the world, to despair at the world’s intransigence and cruelties (in particular as they are visited on Couture himself), to a nascent hope, as symbolized by the Occupy Movement and butterfly migration. “The butterflies are with me,” he writes on the book’s final page. “My change has begun. Change for the world has begun. Hope is renewed. The dream lives.”

I’m happy for Couture in his newfound optimism, but it’s the ongoing potential for another London-style nightmare that should concern the rest of us, and that’s why it’s important to read how the events, almost two decades ago in London, developed, were analyzed and resisted. The case reminds us that bad laws are still part of the Canadian Criminal Code and can be used to demonize, isolate and punish sexual minorities. The legal constraints around prostitution (including the bawdyhouse laws, used to justify raids on gay baths) are the most notorious example, but our laws on child pornography are similarly open to abuse. The age of consent may be 16 (raised from 14 five years ago), but it’s illegal to depict anyone in a sexual context who is, or appears to be, under 18 (there are exceptions if the material is solely for the private use of the individuals who made it). It is difficult to spark public outrage against the law because most people, sensibly, want real abusers caught and punished but don’t picture mid-to-late teens when they hear the word “child.” That’s certainly how Joseph Couture reacted in November 1993 when the London Free Press heralded the uncovering of a kiddie porn ring and began naming the men arrested and charged (“Child Porn Bust May Be Largest in Ontario”). One of the accused was later revealed to be HIV-positive and the Free Press played up his potential for infecting children. “I thought the same things everyone else was probably thinking,” Couture writes. “How shocking and horrible.”

He would soon change his mind. Couture, then in his early 20s, had decided he wanted to work in media. He wasn’t sure how to get started or even what to write about until it became clear that the year’s juiciest story was right on his doorstep. All he had to do was what the straight press had no interest in doing — speak with the men who were charged and the adolescents who were the alleged victims. He had fantasies of selling the story to The Village Voice or the London Free Press, but neither was interested. Xtra was interested, and in April 1994 the first of a series of stories by Couture appeared in this publication. It featured an interview with a politician from the nearby town of St Thomas, a man who was named in the child pornography stories but who was in fact charged only with obtaining the sexual services of someone under the age of 18, in his case a 15-year-old. The boy would later tell Couture how the police had tricked him, promising not to charge him with prostitution or tell his parents if he cooperated, until he came home one day to find a police officer telling his parents the full story.

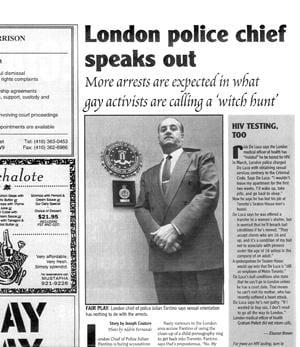

That became a kind of template for the many stories that followed: most of the charges were prostitution related, though straight press headlines referred to child pornography for an unconscionable period of time. Most of the “victims” were street youth on the hustle who often ended up being badly treated by the police and social service agencies. Before long, CBC producer Max Allen took note of Couture’s work and hired him to research what would become The Trials of London, a four-part radio documentary for Ideas that ran from Oct 7, 1994, to May 12, 1995. I would enter the picture in late 1994, thanks to Couture, who hoped I could get the story into the mainstream Toronto press (I wrote frequently for The Globe and Mail in those days). I went for it, got The Globe’s imprimatur, booked an interview with Chief Julian Fantino, and left for London with Couture, who had given me access to all his research.

When we got there, he arranged interviews for me with street youth, local activists and others involved. My story, a 4,000-word piece called “The Kiddie Porn Ring That Wasn’t,” headlined The Globe’s Focus section on March 11, 1995 (the story infuriated Fantino, who would take me and my Globe editors to the Ontario Press Council. That august body ruled that the article, labelled as “Analysis,” should have been flagged as “Opinion” — a slap on the wrist I could live with, particularly since none of the facts in my piece had been challenged). Filmmaker John Greyson also benefited from Couture’s research and contacts: After the Bath, his CBC television documentary on the case, masterfully dissected the sham that was Project Guardian, a police-constructed moral panic aided and abetted by the supine London Free Press (the interviews with its then editor, Philip McLeod, are particularly revealing of the way the newspaper simply regurgitated police press releases).

Couture, on the other hand, though he had no formal training as a journalist, was dogged and resourceful, never giving up on the story, even in the face of threats and intimidation by the London police force. That harassment reached such a pitch that the Canadian Committee to Protect Journalists intervened, writing a letter to Fantino, asking for an explanation. The chief responded, “Mr. Couture quite properly should be concerned about his relationship with and involvement in the Project Guardian investigation; involvement which, in due course, will be officially and appropriately addressed.” As the CCPJ spokesperson noted, she’d written to ask for comments on allegations that Couture had been threatened, and Fantino had responded with yet another threat. “I’d never seen anything like that before,” she said. “He actually wrote it down.” The CCPJ nominated Couture for the prestigious Hellman-Hammett Award from Human Rights Watch, an American organization that created the prize to celebrate “writers who have suffered persecution because of their work and are in financial need.” In 1996, he won it.

It’s a remarkable story. It’s also not the whole story — another weakness of Couture’s book is that the events he records seem to be happening in a sociopolitical vacuum. There’s no context that situates the London events in a period that happened to be charged with hysteria about the sexual abuse of children, real or imagined. There’s no mention that in August 1993 Parliament passed what came to be known as the “kiddie porn” law and that Chief Fantino had actively lobbied for it (thus giving himself a free hand for what he wanted to do in London). There’s no mention that just four months after its passage Toronto police raided Mercer Union gallery, charging artist Eli Langer and the gallery director under the then-new child pornography provisions of the Criminal Code. The Crown eventually dropped the charges against Langer and the director. Instead, Langer’s paintings would go on trial. If found guilty, they would be forfeit to the Crown and destroyed (the trial ended in an acquittal but provided the most surreal moment of those kiddie-porn panic years: it’s hard to believe today, but the actual paintings were on trial, in a court room, leaning up against the prisoners’ dock). There’s no mention of the Robin Sharpe case, which also began to unfold in 1995 (Sharpe, an unsung hero in the defence of free speech, collected photos of naked teens and wrote stories with titles like “Boyabuse.” He argued before the Supreme Court of Canada that the kiddie-porn laws violated his freedom of thought and expression. He didn’t win his case and spent time in jail, but the court did decide to exempt from prosecution personal writings and images intended exclusively for personal use. Sharpe is an old man now, and not in the best of health, but he should be one of our free-speech heroes).

Couture’s inability or unwillingness to see the bigger picture partly accounts for his bitterness and frustration. That’s easy to understand — his work in London should have torpedoed Fantino’s career, but the man went on to head the Toronto police force from 2000 to 2005 and the Ontario Provincial Police from 2006 to 2010. Elected in the riding of Vaughan in the federal election of 2010, he’s now the minister of international cooperation in Harper’s government. Why bother with activism, some might ask? Nothing is going to change.

Back in the day, I would tell Couture, jokingly, that all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds (my Catholic upbringing). I would tell him, not so jokingly, that our guiding rule should be pessimism of the intellect; optimism of the will (my Gramsci-inflected socialism). He would call me Little Mary Sunshine (a reference to which I had to introduce him but which he found, quite correctly, appropriate). Today I’d tell him that you can’t have change without a dream but that change doesn’t happen simply because one has a private fantasy. That’s true only in fairy tales. Change happens when dreams are shared and grow, and not always even then. If some young journalist finds in this story the inspiration to persevere against near-overwhelming odds, Couture’s dream might, like the butterflies he so cherishes, finally take flight.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra