Every so often, an author fictionalizes a noteworthy artist’s story, rendering a remarkable portrait. Unfortunately, Disaster Was My God, which depicts 19th-century French symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud, is not such a depiction. Bruce Duffy’s one-note melody is an unfortunate failing that ponders dull questions and builds to an already-foregone conclusion— spoiler alert —Rimbaud’s death at age 37 from cancer.

Rimbaud is actually fascinating. His devotees still leave gifts at his gravesite. The poet cut a wide swath through 19th-century poetry and literature, a remarkable feat for anyone, much less a 16-year-old enfant terrible fresh off the train from Charleville. He decried emotionally laden poetry and bland French works, seemingly channelling a non-linear, vagabond, realist voice that shook the pillars of established writing and institutions, including marriage.

Rimbaud also absconded with fellow poet Paul Verlaine, who enthusiastically abandoned his wife and young baby for the rogue. The lovers roamed the countryside raising Cain for several years. Then, uproariously, Rimbaud denounced poetry writing around age 20 and abandoned Verlaine.

Followers have always wondered why he quit, including Duffy. His characters subtly and not-so-subtly ask themselves, each other, and Rimbaud this question. He replies only in exasperated platitudes. Duffy also ponders whether Rimbaud secretly wrote again; he answers this, too.

Duffy constructs entire scenes around heaps of quoted verse that act as scaffolds. He suggests that the inspiration for Rimbaud’s poems about wandering the countryside, for instance, flowed from him repeatedly journeying 200 kilometres from Paris to Charleville.

All this sound and fury about Rimbaud, however, has been done better. The 1995 film Total Eclipse, based on Christopher Hampton’s 1967 play, starred Leonardo DiCaprio as Rimbaud and Paul Thewlis as Verlaine. DiCaprio elevated this moderately good movie through his engrossing interpretation. Well-cast Thewlis did likewise as notoriously homely Verlaine. They debauch, they write, they attempt to revolutionize love; instead, they break up and settle for changing the face of symbolist, Dadaist and surrealist poetry.

Meanwhile, there is little enlightening in Duffy’s book. Although he tries to add allure by theorizing that Rimbaud’s mother was stifling, he adds only expositional writing. In nearly all of the widow Rimbaud’s scenes, she lists her maternal grievances or tells daughter Isabelle that Rimbaud has amounted to nothing. All family members, in fact, speak in a stilted style, revealing as much as possible about their characters. When Rimbaud returns home from 10 years abroad in Ethiopia, he tries, unsuccessfully, to reconcile with his mother. Duffy portrays her as mercilessly cold and distant. Duffy also writes short scenes, drawing readers in and moving on before they can latch onto anything.

By the end even the most ardent Rimbaud follower will stop caring so much about why this bratty ingénue abandoned writing. Duffy suggests reading Rimbaud – a wise suggestion and better choice than reading his Disaster.

The Deets:

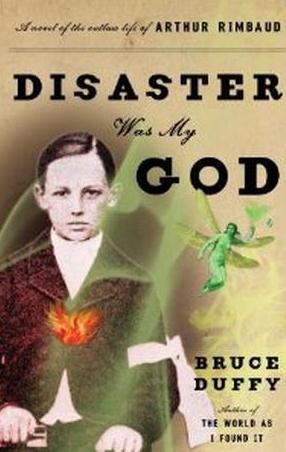

Disaster Was My God: A Novel of the Outlaw Life of Arthur Rimbaud

Doubleday

$32

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra