Are you high or drunk and listening to some sad break-up song? I might be. There is no shame in admitting to one, both or even all three of these possibilities. If you’ve been doing them on a regular basis, especially during this pandemic, welcome to the world of at least one in five gay men. Between 20 to 30 percent of the LGBTQ2S+ community struggles with some form of substance use disorder, which, according to groups like the Canadian Mental Health Association, is significantly higher than among straight people.

When I logged on to Spotify to listen to the new single “Lovingly, Letting You Go” by Toronto electro-pop house music artist Danny Dymond, I was sure, after my first of many listens, that he was singing of a love gone sour. Perhaps it was the title, the lyrics or the down tempo electro beat that made me picture him calmly saying goodbye to someone he once loved—or maybe I was just used to listening to break-up songs. Lady Gaga, Katy Perry, Taylor Swift and Adele are just a few of the artists who’s sad songs I’ve happily turned to. But Dymond’s split was different.

“It’s actually a breakup with a lot of my bad habits,” Dymond says over the phone one frigid winter afternoon. “Drug use, bad decisions, shame and guilt from being a hot mess,” he continues. “When I was first coming into the gay community, I drank way too much and did a lot of drugs to mask my social anxiety. I thought I couldn’t handle going out and being around a lot of strong personalities without getting intoxicated and getting those nerves gone. It’s a break up about that.”

The intro to “Lovingly, Letting You Go” is slow and thoughtful, leading into a sexy, atmospheric beat reminiscent of a sweaty warehouse party that carries through the rest of the track. It is in the quiet moments we hear Dymond’s seemingly emotionless explanation of a decision that is yet to come. There is no anger or sadness in his delivery. It’s as if he’s had a while to process his substance use and understand its hold over him, and he’s clearly over it. It’s not a tumultuous ending of what was once a fun ride; the ride has simply come to an end and he wants off.

Coded lyrics are charged with ambiguous ammunition. Lines like “Your love is just a riddle, a devastating crime,” “Going through the horror/ Working through the pain,” “Your love isn’t equal/ All is on the line” and “Give me what I need/ Ya, ready to let go” could easily be directed at a mysterious man who sucked the love out the artist instead of a not-so-mysterious substance that he has snorted up his nose. The lyrical conversation we are privy to is not with another person, but with Dymond himself. For those battling substance use disorder and those fighting for the survival of a relationship, this conversation can be eerily similar. Love, like drugs, can be an addiction if one feels that they, alone, are not enough.

Dymond says the song—which took more than a year to get produced—was originally a love song that morphed as Dymond’s relationship with his substance use evolved and, eventually, dissolved.

“Love, like drugs, can be an addiction if one feels that they, alone, are not enough.”

Having received the instrumental backing track from a ghost producer a few years ago, the music sat in his mind as he waited, drank and snorted for the right lyrics to come. Over the course of a year, just before the world went into global lockdown, he wrote his initial drafts. But it would take the isolation and social upheaval of the past year for the song to evolve into what we finally get to groove to. The melody changed, the vocal composition became layered and distorted and the lyrics worked through him more honestly.

“When I write a song I come up with a feeling that I want out of that track,” he explains. “Is it more emotional, is it more chill or is it a party banger? If I commit to that one idea then all the other elements fall into place.”

The producer that Dymond had been working with for years (including on his dirtier electro debut album, Nightlife, Love & Liberty, released in 2018) suddenly decided to retire and stopped the project half way through. With an unfinished track on his hands, Dymond had to find a new producer during COVID-19 shutdowns—no small feat.

“It was like a Frankenstein project,” he sighs. “A different ghost writer, a different producer and a different recording person.”

His new producers, Daniel Monsier (who mixed and mastered the track), Liam Medina (who recorded his vocals) and Dowden (who remastered the vocals), added vocal echoes and distortions to enhance the song’s sound. And the direction change was a good thing: When COVID-19 first hit, Dymond was at his lowest. Trying to keep busy, he was still partying all the time, and the change in routine played havoc with his creative process. Even with some government money coming in, he still wasn’t financially stable and found he was making a lot of bad decisions as a result. That’s when the song began to reflect Dymond’s struggles.

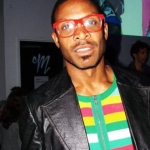

Credit: Courtesy of So Fierce Music

“Even still, I‘m not Sober Sally,” he laughs. “I’m not perfect by any means. But I’m not railing cocaine three days a week. Cocaine was killing my soul. It was making me not want to be creative. It was making me self-sabotage and do risky things. So it’s nice to release a song that has some meaning to it and not just a club banger.”

Dymond believes the queer clubbing community is driven by a lot of strong personalities where everyone is trying to make a name for themselves. He sees the industry as a place where people like to have fun and let loose, but also entertain and get ahead. In between those two supporting columns is a lot of room to fall down stairs and get lost.

“My biggest regret is that I allowed myself to be seen in a light that I didn’t want [people] to see me in. You learn who you can trust and who you can’t,” he says. “I’ve learned that there are party friends, but they aren’t going to be your real friends. A lot of people are around for a good time, not a long time.”

This is the second last song that Dymond will be releasing as an independent solo artist with GODDEXX (who Canada’s Drag Race star Scarlett Bobo and Two-Spirit trans recording artist Quanah Style have both worked with). Dymond recently signed with So Fierce Music, a new, Toronto-based label formed last summer by recording artist Velvet Code that exclusively promotes and supports queer artists worldwide.

“I don’t have to worry about having all the work load on me,” Dymond says. “I can focus on my online presence, my music and performing—if we are ever allowed to again—instead of having to worry about the marketing aspect.” Now, he can also concentrate on himself; the path to substance recovery, he says, is not a short one.

“I’m in a much better place,” he says. “I’m working out, eating healthy and even meditating, and trying to be a loyal person. It’s a journey.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra