Reading a Christopher DiRaddo book is a strange experience, because he writes with such clarity about his characters that they seem like people we’ve known for years. He conjures up fictional people who feel eerily familiar. Opening up a book feels like walking into an intimate dinner party with a tightly-knit group of old friends.

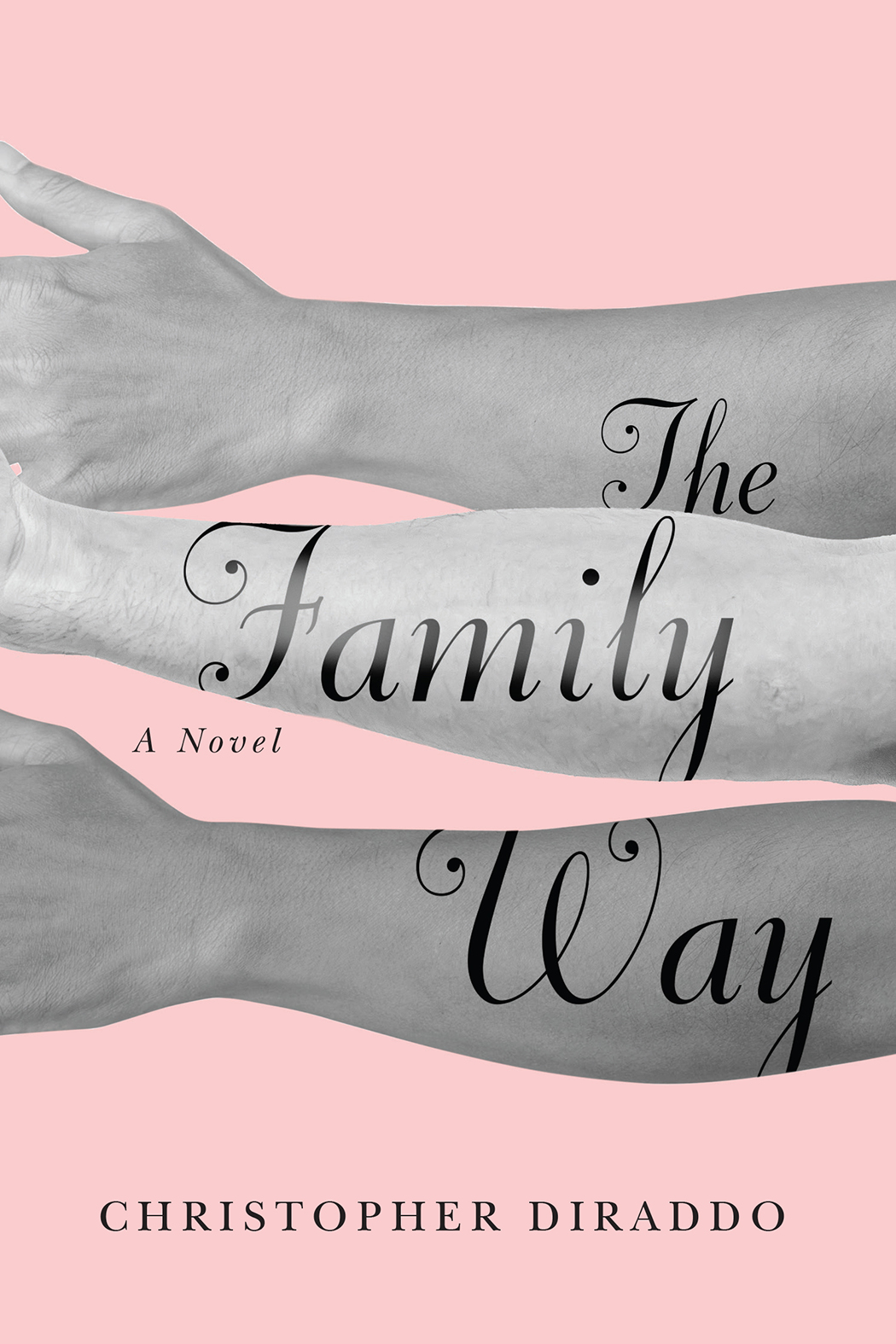

In his first novel, 2014’s The Geography of Pluto, DiRaddo wrote about the romantic bumps and scrapes experienced by a queer Montreal teacher. In his latest, titled simply and elegantly The Family Way, we meet Paul, a confident 40-something who is approached by his close friends, a lesbian couple he’s known for decades, about being their sperm donor and helping them have a baby. Gently humorous, unpretentious and intensely rewarding, DiRaddo’s writing is queer-affirming while never being maudlin. At one point, another close friend of Paul’s offers his own queer take on Groundhog Day: “Is it true that if a gay man sees his stomach the first week of February, he has to do six more weeks of CrossFit?” It’s a rare gift, and Montrealers will feel especially rewarded as DiRaddo has again made the setting an inherent part of the book’s charm: We visit some of the city’s infamous queer drinking holes, like Sky and The Stud, and drive through Old Montreal and past Habitat 67.

It’s also a pretty brazen, barely-veiled autobiography. DiRaddo laughs when I ask him about this. “I try to base all my writing in something real, a lived experience,” he says. It being a pandemic, I called him at his Montreal home.

This being your second novel, you’ve definitely developed a style. Your writing is frank and the characters and dialogue feel entirely real. Which queerlit writers would you say are your biggest influences?

Andrew Holleran is probably my biggest influence. All of his work is just so beautiful and smart and witty and honest. If I can write a sentence like him, I’m happy. I also love the way friendships are portrayed in Ethan Mordden’s books and long for the day I can produce something as epic as How Long Has This Been Going On. Screenwriter Joe Keenan (known for the TV show Frasier) wrote a series of hilarious novels that I love returning to. There are many others too: Sarah Waters, Michael Cunningham, Scott Heim, Sarah Schulman and Felice Picano, to name a few.

“Now we can get married, and both be on a child’s birth certificate. But what if we don’t want that? What if we prefer to host dinner parties, take holidays and grow old alongside our best friends?”

It is refreshing to read about queers who are forming families in new ways. I think we need more books like this one.

I agree. I’m actually surprised there aren’t more stories out there like this. God knows, there are enough books about emotionally unavailable gay men in their 20s trying to get laid—and I already wrote mine! I guess, as I get older, I’m more interested in what happens after the chase. Also, we as queer people have long had to fight for our relationships to be seen as legitimate in the eyes of the public, the government and our biological families. Now we can get married, and both be on a child’s birth certificate. But what if we don’t want that? What if we prefer to host dinner parties, take holidays and grow old alongside our best friends—some of whom might even be our former lovers—who have been with us through thick and thin? I think we need to legitimize those relationships as well.

Credit: Véhicule Press

Attitudes towards queer families and queer parenting have changed very rapidly. Have you found this surprising?

Not really. I cut my teeth working for gay Pride in the ’90s, and that was a part of our mission—change mainstream society’s perception of LGBTQ people. And we succeeded. Sorry, everyone! Like Paul, I helped good friends start their family. And when I tell people this now, I get so many smiles and questions. People are genuinely happy for me and my friends; they’re very curious about what the experience was like and what it’s like for the child. I don’t think I could have imagined this reaction in my 20s. Still, procreating is not for everyone. Even though many more queer people are doing it, many are not. I tried to show that in the book, too.

At times, it felt like Montreal itself was another character in the book. You describe neighbourhoods and talk about going to The Stud. I really love that, because Montreal is a city that’s very open, very inherently queer.

When I read fiction, I love getting a sense of place—whether it’s Berlin, Tokyo or Chicago. I also find myself very inspired by Montreal. So much has happened to me in these city streets that when I’m working with characters, I find that I’d rather drop them into locations I already know rather than invent new bars or restaurants. [Canadian writer Mordecai] Richler wrote about his Montreal; [Canadian playwright Michel] Tremblay wrote about his, and I’m writing about mine. It’s like my own version of Coronation Street. And I have to say that during the pandemic, it’s been great to lose hours with my characters in bars I can no longer go to. The Stud might be one of the first places I visit once this is all over.

I recall you speaking with some trepidation about your parents reading your first book. How was your comfort level this time around and how did they respond?

The only two critics I really care about are my parents. They’ve been wonderfully supportive, but there’s always an adjustment period. They didn’t know much about the LGBTQ world before I told them I was a part of it. Even though it might seem alien to them at times, they love and trust me enough to walk in the direction I’m leading them. Still, I don’t ever want to feel like I’ve let them down. When you write, you’re putting your mind on display. And even if you haven’t done all the things you’ve written about, you’ve thought about doing them. It’s one of the most vulnerable things you can do—sharing your private thoughts with the rest of the world. I’m always worried they might judge me for my imagination, but they haven’t. They’re very proud of what I’ve accomplished.

You created and host The Violet Hour, a queer literary event in Montreal that is very popular. How much effect would you say curating events like that has had on your own writing?

It’s had an effect on how I think of readers. Before I started the reading series, I wondered if anyone still read LGBTQ books anymore. Well, the answer was a resounding “Yes.” People remain passionate about books and now, when I write, I know there’s an audience for these kinds of stories. I’ve also got to meet so many wonderful writers doing the same thing as me—putting their heart and soul into their work and then trying to find a home for it. In the last few years, we’ve built a community around queer books, and it’s been affirming. I feel like I’m finally where I’m supposed to be and doing what I need to do.

Do you see any difference in queer titles being published in French in Quebec than what is being published in English in the rest of Canada?

I’m not an expert on LGBTQ lit in French, but I have noticed a few things. More and more, I invite French writers to read at The Violet Hour and I love the interaction on stage and with the audience. Still, I find it hard to find a variety of queer voices to feature on stage in French. The province seems to publish more English QBIPOC [queer Black, Indigenous and pPeople of colour] writers in French translation than those who are originally writing in French. However, that seems to be changing, with more writers like Kama La Mackerel, Nicholas Dawson and Marilou Craft leading the way. Hopefully we will see even more diverse queer works being published in French in Quebec in the near future.

The Family Way by Christopher DiRaddo is published by Véhicule Press

The virtual launch of The Family Way will be hosted by Montreal’s Drawn & Quarterly bookstore on May 27 at 7 p.m. EDT. Christopher DiRaddo will be in conversation with Xtra’s Rachel Giese.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra