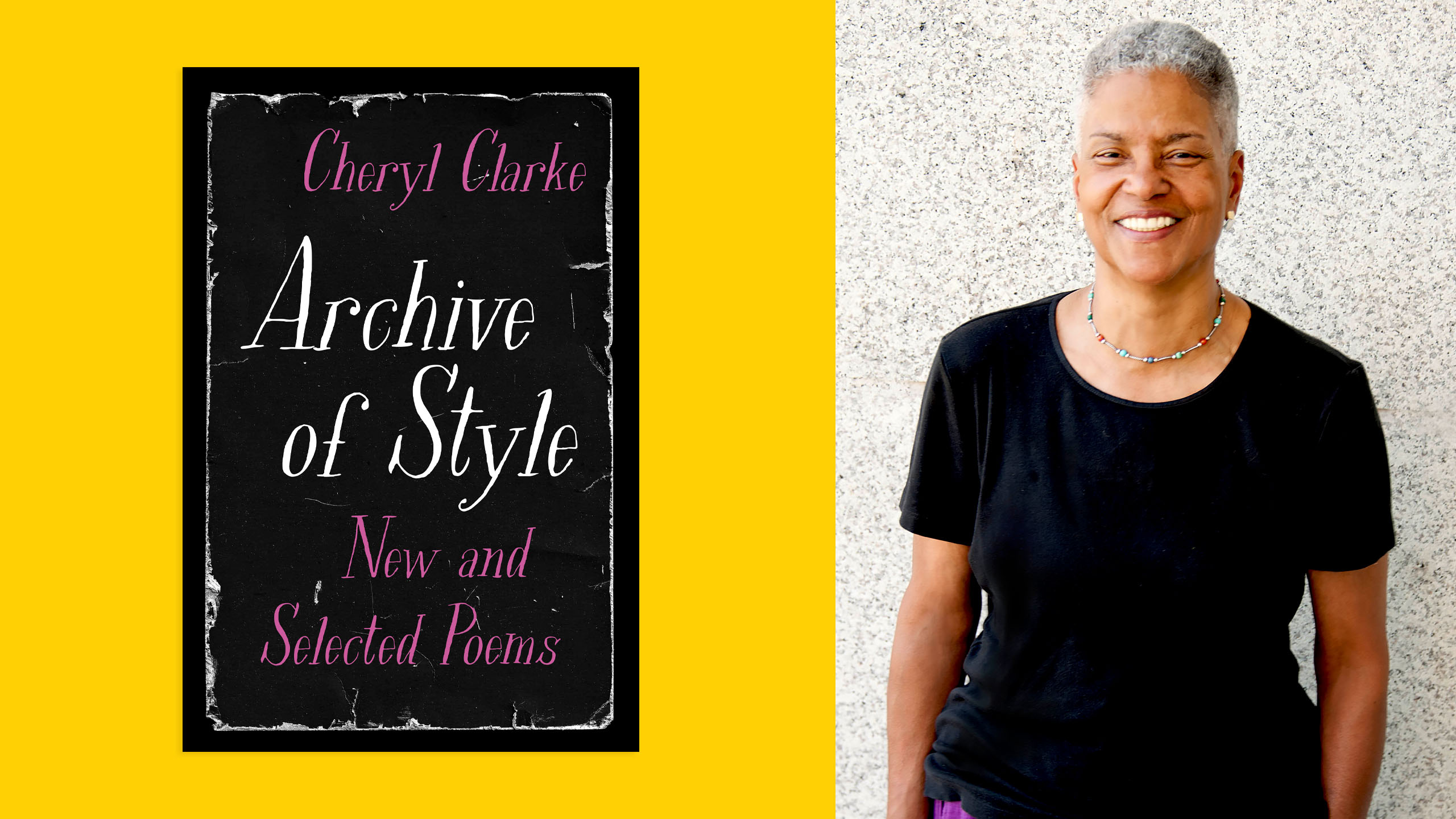

“Legend is history, in the sense that it tells of a past that is fictional and real,” Cheryl Clarke explains to me one evening as we talk about the role of legend in Black history. On Aug. 15, Clarke is releasing a collection of poems spanning from the beginning of her career to new, previously unpublished works, titled Archive of Style: New and Selected Poems. Some of these poems deal in legend; from fictionalized stories of real events, to undeniable fact.

Many prominent lesbian poets and activists emerged in the 1970s. A few names that come to mind are Audre Lorde and Barbara Smith. Cheryl Clarke also started publishing around this time, a poet who wasn’t afraid to talk explicitly about sex and love between women, as well as the pressing topics of the day like apartheid and racism.

The collection contains poems from popular works like Humid Pitch (1989) and Living as a Lesbian (1986). In addition to her work as a writer and activist, Clarke is also one of the founders of the Hobart Festival of Women Writers, which, founded in 2013, takes place each September in Hobart, New York. The early pandemic years saw the festival cancelled, but it resumed in June 2024 according to their website. She’s also the former director of the Office of Diverse Community Affairs and Lesbian-Gay Concerns at Rutgers University.

Clarke’s poetry, along with her criticism, are legendary. Whether you’ve known her work since your freshman feminism seminar, or are just finding out about her, you’ll find her work has been crucial in the feminist literary space. During our conversation, we talked about how activism and creative work are inexplicably linked.

“Writing is for me ‘advocacy and activism.’ This is why people call my poetry ‘political,’” says Clarke. “Because it presents issues of power, for example, feminism, blackness, LGBTQ2S+ issues, various events and issues of Black history, like police brutality. I am a feminist, and, for me, women, many of them lesbians, are at the centre of my creative work, are the subjects of my work.”

We discussed Clarke’s work on the defence committee for Assata Shakur, a political activist and member of the Black Liberation Party who is currently seeking asylum in Cuba. She details harassment from the police and the FBI during the ’70s in New Brunswick, New Jersey, where Shakur was being tried.

“You also had to be bothered with the FBI, who would follow you sometimes in your car. Their harassment went on from 1976 until the late ’70s. They would come to your job to question you, they would question the people you work for and with,” she recounts. “They harassed your neighbours. They stopped my lover’s mother once when she was leaving our house. They came to my parents house in Washington, D.C., as well.”

In Archive of Style, Clarke has a poem about the more recent injustices that Black women face, memorializing Sandra Bland, who was killed by police in Texas in 2015. The poem begins with “Five years, Sandy, since you met your nasty fate,” and goes on to describe the events of that day, recalling Bland’s defiance and resistance.

There are other poems about police murder as well, recounting the murders of George Floyd, and poems for Black women, like Breonna Taylor, who have faced similar deaths as a function of patriarchal violence. This topic isn’t a new one to Clarke—she’s been writing about the violence of patriarchy for decades. When asked about what has changed in that time, Clarke says:

“The same things continue to occur. However, we know more about them now because people are more aware and understand how to get the word out. And also I think police are more emboldened—in a way—to attack Black people, to keep us in line, like the incident in Illinois of the woman, Sonya Massey, [who] was shot in the face and killed by a rogue cop,” Clarke says. “I am still captivated by the novel forms racism takes, like the poem ‘Targets,’ or ‘capital car chase,’ but then because of the prevalence of guns, you have events like Uvalde, Texas or Mother Emanuel Nine, so it is not just cops killing Black people and Black women.”

In one of her more well-known essays, “The Failure to Transform: Homophobia in the Black Community,” Clarke calls in Black men and women who are straight, and consider themselves intellectuals, who have shunned Black lesbian radicals, considering them “detrimental” to the community. The anti-Blackness that results in the murders of Black people, and the homophobia that ousted many Black queer people from the community, are linked; some might call them a plea to white supremacy.

There are, of course, different gradations to violence, and Clarke acknowledges this in her work. In one of my favourite poems from the new book, “a child die,” Clarke ends the first section of the poem with the line: “reticent naming is not witness enough.”

Lots has been said about the role of witness in poetry, so I get Clarke’s take on this final line.

“There is never enough ‘naming’ or ‘witness’ of violence, until the violence stops. Part of the reason I write these poems is so that people can witness and find ways to stop violence against women. Violence stops women from living on many levels. And aren’t we tired of that?”

Clarke expands on this later in an email:

“The important thing for me in writing about, for example, womanhood, lesbian life and Black experience in 2024 is to keep writing about those specific issues because women, lesbians and Black people continue to struggle for freedom and against the effects of four hundred years of African enslavement in the West, centuries of misogyny everywhere and years of heterosexist domination/dominance in the U.S. and in most places on the globe,” she writes. “It means almost the same thing to write about race/racism, sexuality/homophobia, gender/sexism as it did when I started publishing in 1979.”

In Archive of Style, poems about love and sex coexist alongside the poems people would consider explicitly political.

In “Make me a habit of you” Clarke writes:

“[Make me a habit of you]

was my invocation thirty-two years ago

when I cast all caution for your love

onto the Atlantic seacoast.”

Many such poems of desire and tenderness populate the new and selected portions of the book. In her poem titled “sexual preference” from the Living as a Lesbian portion of the selected works, we see the lines, “your tongue does not have to prove its prowess to me/ there/ yet.”

Clarke tells me that around the time she started publishing poetry in the early ’80s, not much was written about (at least not explicitly) sex between women, and she took to writing these poems out of her own desire to see them, but also for the benefit of other lesbians and queer women.

Clarke continues to centre the Black lesbian experience in her work. From her seminal essay, “Lesbianism: An Act of Resistance” from This Bridge Called My Back, an anthology of feminist writings, edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa, published in 1981, to her new poems like “Cost” and “I Love You, Love You Anyhow,” she portrays the beautiful and often complex world of lesbian life.

Archive of Style presents an in-depth look at Black queer women and their lives, their struggles and triumphs, the things they care about deeply and what moves them. It’s also a snapshot of a career worth championing, Clarke is undoubtedly one of the most powerful Black queer minds in the current landscape, and with this look at her life’s work, she cements her legacy.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra