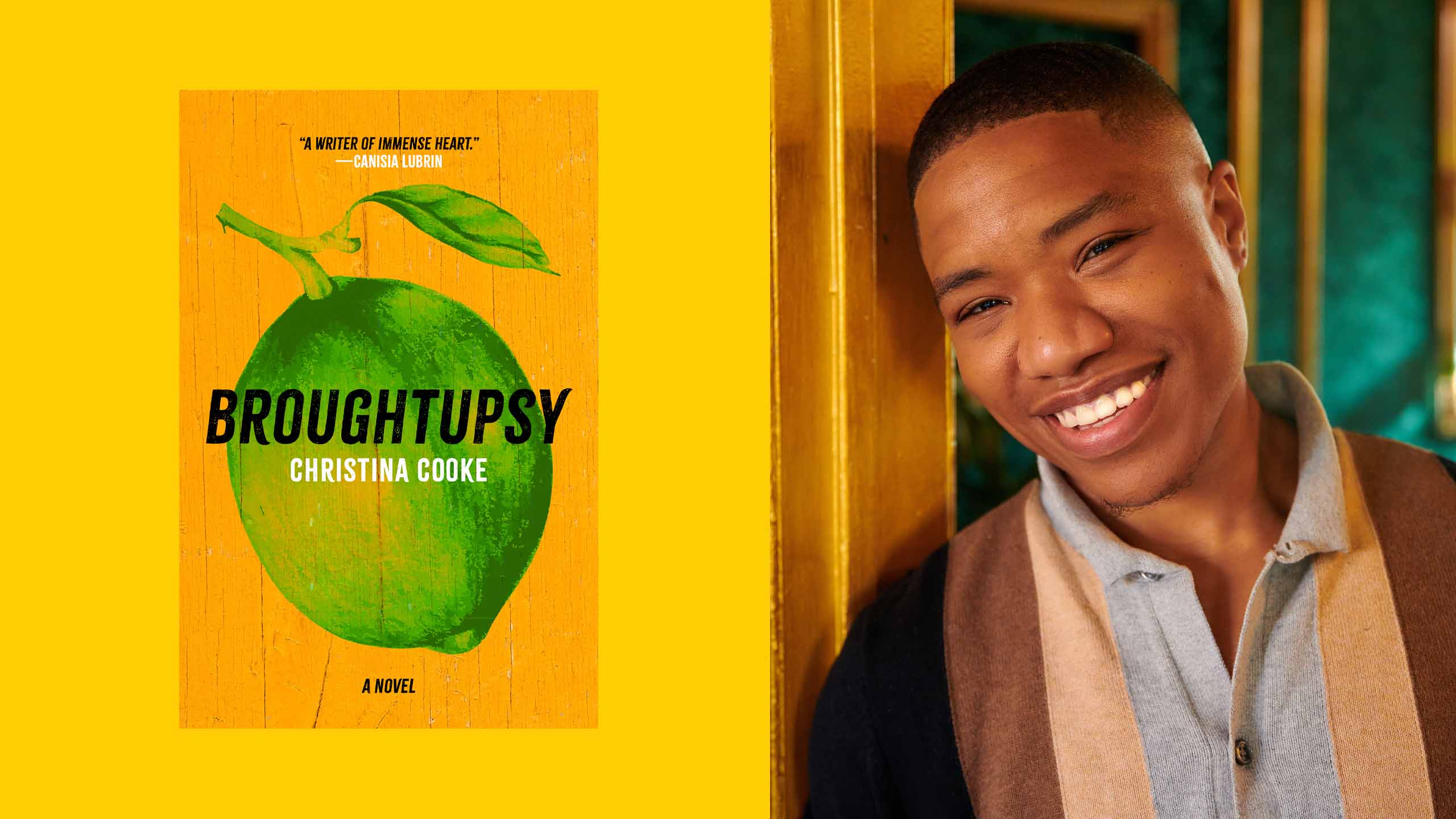

Christina Cooke’s debut novel, Broughtupsy, is a deep exploration of what it means to live life at the intersection of various identities, as a queer immigrant and person of colour. Published in January by House of Anansi Press, Broughtupsy follows protagonist Akúa as she attempts to reconnect with herself after her brother passes away. Having spent the first decade of her life in Jamaica before moving to Canada, she travels back to Kingston to retrace her childhood.

In Kingston, she works on patching up the fractured relationship she shares with her sister, Tamika. Akúa is forced to reckon with the complexity of being a queer woman in a religious family and what that means in Jamaica, a country where LGBTQ+ people regularly face violence and discrimination. Along the way, she meets Jayda, who quickly becomes a bold and shocking reminder of what her life could be.

With Akúa questioning the validity of her own Jamaican identity, Cooke weaves a rich story rooted in the complexity of being a queer immigrant.

Xtra speaks with Cooke about the experience of writing a first novel, the trickiness of intertwining reality with fiction and why spirituality is undeniably queer.

Have you always been passionate about telling stories?

Yes. It’s funny … both of my parents were full-time engineers, so when 12-year-old me said I wanted to write stories, my parents were very confused. Looking back, though, one of my mother’s favourite tactics during the summer breaks we spent in Jamaica was to sit my siblings and me down with stacks and stacks of books. She was an avid reader, so she would find every book appropriate for our age range and she would get it from the library. Our job was to read as many of them as we could because then she would ask us about them. So, they actively encouraged that in me for four months of the year, every single year, for years. How were they surprised that I became a bibliophile?

When did you first get the idea for this book?

The thing that people find most surprising is that from the original seed idea to the final finished copy I have now, that whole process took 13 years, which is an unreal amount of time. But I don’t think I could have written this novel any faster than I did. The flashback scenes throughout the book are visceral and immersive, but I could only write that because I was twenty-two when I began writing this. The protagonist of my novel is twenty, so it didn’t take much to try to leap out of my life and into hers.

It then took me becoming older to almost pull my head out of the trees and see the whole forest. It took me living my life and maturing to understand how to organize all of those pieces into a kaleidoscope that would make sense and feel compelling to somebody other than myself.

What made you want to write this particular story?

I wanted to write something that reflected a multi-layered and multifaceted sense of being that I didn’t see in the literature that was being published when I began writing. I’d read so many books about Jamaicans leaving the island. I’d read so many books about Jamaicans who had left the island and were now living abroad, reflecting and going back. I started to see books about queer Jamaicans in Jamaica. However, I didn’t see anything that combined all three, and so it just felt like there was this gap in the literature. It’s one of those things where you can be mad or you can be a part of this solution. I decided to be part of the solution.

Tell me the meaning of the term “broughtupsy” and why you chose it as the title.

Jamaicans will try to say it’s our term, but it’s not. It’s a phrase that belongs to the full Afro-Caribbean region, which refers to having good manners or being brought up well. So much of this novel is not just a coming of age, but also a coming to consciousness, in the sense of my main character starting to understand herself and understand all the forces that made her. Then, for me, this idea of how you were brought up, how you were raised, how you were conditioned, seemed like the perfect way to encapsulate everything that the novel is about. “Broughtupsy” became the perfect fit.

Like Akúa, you’re a first-generation immigrant from Jamaica, you moved to Canada when you were younger and you’re queer. How much of the novel is based on your real life?

This novel is all made up; it’s all invented. In the novel, Akúa is the middle child of three, and multiple members of her immediate family pass away. My life is nothing like that. In terms of the facts and how her story unfolds—that did not happen to me at all. The overlap that does exist is that so many of the emotional realities that Akúa confronts in this novel are very similar to the emotional conundrums that I’ve faced as well.

Because I was so young when I began writing, I had just exited the period in my life where all this self-discovery was happening for me, so it was fresh. Right after going through it, all the machinations were so fresh that I quickly had to write it out. That is also probably why I have a real spiritual connection with this novel. So much of the formation of who I am as a person is in my book.

How much have your own intersecting identities played into these characters?

Oh, so much! Part of what motivated me to write this novel is that people loved to throw around the word “intersectionality” in the 2010s. “Intersectional” became a grad school word, used by people who didn’t know what it meant, who just wanted to sound smart and progressive, and it just pissed me off. It just made me mad because did they even know what “intersectional” looked like? Did they know someone who embodied that? It just felt like a trendy new idea for people.

I am a Black, queer, gender nonconforming immigrant. I have a stutter. I have so many “isms,” but they do not define me. I define myself by how much I love Negronis and hate winter. Real intersectionality is a thing lived, not a thing considered. I don’t go around thinking about how queer I am. I do go around thinking that I’m hungry, though.

So I wanted to create a character that lived inside of intersectionality, taking all those “isms” and giving her a name, a face and a full, rich life.

One character that stands out is Jayda—she’s a queer stripper in Jamaica who is bold and full of life. What was the inspiration behind her?

The relationship between Akúa, my main character, and her sister, Tamika, is deeply complicated, difficult and heavy. So I wanted a source of light, fresh air and fun—that’s where Jayda came in. She was so fun to write! She’s spunky, she takes no shit and she just always takes the lead. She was light in a way that provided relief from the weight of the sibling relationship.

The novel also needed her because in a sense she represents a kind of queer Jamaican-ness that’s of the land, instead of being just of the mind. She’s not thinking about how to be queer in Jamaica. It’s just in her body. She’s just living it. As Akúa grapples with her seemingly separate identities, Jayda represents everything she wants to be. Overall, it felt like Tamika and Akúa kept going in circles, asking the same questions, until I wrote Jayda to break up that tension, allowing Akúa to spiral off into her own sense of freedom.

The book digs into the themes of exploring sexuality or even rediscovering sexuality during a time of loss. Why was it important to you to look at these specific themes?

I wanted to complicate this trope of a “coming out” story. I’m not saying “trope” to disparage it at all because I do think that it is such an important type of literature to have. But as someone who was brought up in an age where it was everywhere, I saw it as my responsibility to take that trope one step further and to complicate it.

To go back to this idea of intersectionality that is lived and not just talked about, there’s also the intersection of different life forces, impacting you simultaneously, while you’re trying to figure out how to be a full person. It’s not that I went into it wanting to understand what it meant to figure out your sexuality while dealing with loss. I just wanted to figure out what it must be like to reckon with your queerness, in conversation with the rest of your life.

Talk to me about how you came to explore the idea of being queer in a religious family.

The substance of this theme in the novel was inspired by my own life. My grandfather was an Anglican priest. My uncle in Jamaica is the secretary of the Anglican Archdiocese of the Caribbean. Religion is a huge part of my family history, and my family culture. But when I came out, I wasn’t banished from the family. I consider myself quite lucky, actually. Everyone had their questions, but they accepted me. They didn’t understand it, maybe at all, but they still let me know that they loved me.

That got me interested in the idea of religion and spirituality. Queerness and spirituality are not in opposition to each other. If you are being your full self as the higher deities intended, then you are wholly right, you are living within the fullness of your presence and purpose. So queerness and spirituality are intertwined.

Queerness and religion, on the other hand, conflict because religion is man-made. Religion takes spirituality and turns it into an institution, and institutions are made by people and people are flawed. Therefore, institutions are flawed. I think that the fact that my family was able to accept me was because believing in a God and being connected spiritually trumped the rules of the Church.

So that’s one of the things that I tried to strike a balance between in the novel; to show how queerness, Jamaican-ness and spirituality sit in association with each other. It’s this man-made, flawed institution of religion that is the thorn.

In the book, Akúa questions whether she is “really” Jamaican. Where do those doubts stem from?

I think that Akúa’s questions about her identity are connected with the universal questions around migration. I read Salman Rushdie’s Imaginary Homelands while writing the novel, and it inspired me. The way he questioned his own Indian-ness, having lived away from Bombay for so long, was similar to what Akúa was wrestling with. She defines herself by an idea of Kingston that’s been frozen in her head from when she was ten. Now she’s twenty. That divide between “feeling” and “knowing” gives rise to Akúa’s questions about where she truly belongs.

And how does queerness impact how she views her own Jamaican-ness?

Queerness is hotly contested in non-white communities. What often has to happen is what I call this “boomerang of evolution” where you have to leave your cultural community and go out into these queer spaces simply to exist. These spaces have historically almost always been coded as white, but that is where you finally have the space to relax into your sexuality and be able to kind of explore that aspect of yourself.

But then at some point, once you start to fully relax and take ownership, you look around and you realize that you have traded one part of yourself for another. Now suddenly I might feel very uncomfortable being Black. I might feel very uncomfortable being Jamaican. Often you have to go out to find yourself as a queer person, then you have to come back to your original cultural community to reclaim yourself as a full person, and it creates this frantic back and forth.

I want to be able to say “broughtupsy” again where people know what I mean. For that, I have to be around Jamaicans. But I also want to be able to talk about how that girl is hot and how I want to ask her on a date, so then I have to be around a community of queer people that is predominantly white. So for Akúa, and most queer people of colour, the idea of herself as queer truly complicates the idea she has of herself as Jamaican and as an immigrant.

What advice would you give to queer and BIPOC writers hoping to express themselves through novels like Broughtupsy?

Firstly, take the things that you value as beautiful and true, and then dig deep. One of the things that I always thought was beautiful was the idea of Jamaican folklore, and so I just went deep into that rabbit hole. I truly immersed myself in it so I had a more nuanced, clear and accurate language for it. Simultaneously, I would also recommend reading widely because it can open your mind to the endless possibilities of playing with language.

Create an unlikely intellectual cross-pollination—take what you know so deeply and express it in a way that is fresh and uniquely yours.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra