Writing a novel is an act of sheer insanity says Wayne Hoffman.

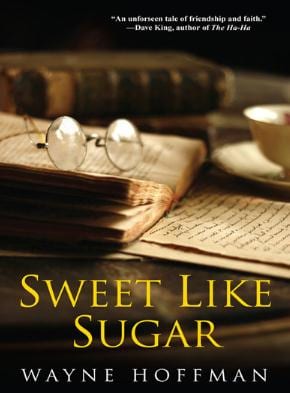

Gay literature is rife with stories about bonds between gay men and women, but in his new novel, Sweet Like Sugar, New York-based writer Wayne Hoffman examines the bond between a gay man and a straight man. In elegant prose, the author tells the story of Benji, a 20-something gay man who befriends an elderly rabbi who has recently been widowed. The story unfolds beautifully, as Hoffman reveals how the young Benji — a man who has become quite cynical — learns potent life lessons from the rabbi.

Tales like these too often veer into the maudlin, but Hoffman’s keen sensibility and lively wit mean he avoids the sentimentality trap. It’s a smart book, written by a man who has become renowned for his numerous short works of fiction, as well as his cultural commentary — everywhere from the Village Voice to The Washington Post. Hoffman spoke to Xtra from New York, where he recently won a Stonewall Book Award for Sweet Like Sugar.

What inspired Sweet Like Sugar?

Wayne Hoffman: Years ago, I was managing editor of The Forward, a national Jewish newspaper, and the editor of our sister newspaper, The Yiddish Forverts, asked if one of his staffers could lie down on the couch in my office. I said yes, and a very old, very sick Orthodox man came in and went to sleep while I worked. Looking over at him, I started to wonder: we work in the same office but have never spoken, and I bet we have nothing in common – me, a (then) 30-something gay atheist, and he an Orthodox, Yiddish-speaking man in his 80s – and yet our lives have intersected in this very intimate moment. I tried to imagine what we might say to each other when he woke up. How would our conversation go? What could we talk about, argue about, agree on? That turned into the opening scene of the book. I’d been juggling my dual identity as a gay Jew for my whole adult life, so naturally that became the basis for the rest of the novel, which that opening scene allowed me to explore.

You have written a number of short stories. What’s the main difference between writing a short story and writing a novel?

It’s the difference between running a few blocks and training for a marathon. Writing a novel is an act of sheer insanity that requires completely unrealistic amounts of stamina. This by no means implies that writing something shorter is less valuable; part of a writer’s job is to know what form a certain story warrants. But these are different animals, beyond the obvious question of length. A good short story is like a wonderful weekend away: you see a few new things, step outside your own world for a moment, and then go back home. A good novel is like living on another planet: you have to learn the language, the landscape, the people, the social conventions, and you’d better hope you can breathe the air there, because you’re not going home for a long time. This is true for the reader, but it’s even truer for the writer; it takes a few days, a few weeks to read a novel, but it takes years to write one.

Joan Rivers once told me why she thinks there’s a strong Jewish-gay connection: “It’s about survival,” she said. Being both gay and Jewish, how do these two identities connect for you?

There are certainly similarities. A strong sense of community – one that actually encourages dissent and diversity of opinions (on a good day). A strong hunger for social justice. And a strong belief in family – even if the gay community’s chosen families don’t resemble biological families on a superficial level. Both identities involve learning how to survive as a minority that’s sometimes invisible and often misunderstood, occasionally fetishized and frequently reviled. And don’t forget, without gay men and Jews, you wouldn’t have musical theatre. And without gay men and Jews, the only comedians left in America would all be Canadian.

Look at it this way: I’ve written two very different novels – Hard is an extremely explicit book about AIDS activism and sexual politics in New York City, while Sweet Like Sugar is a much gentler story about faith and fate in the suburbs – but both have gay Jewish protagonists. They’re very different guys who probably wouldn’t like each other much if they met, but their very different lives as gay Jews have a few things in common: both books contain scenes set at Passover Seders, and both books have Fiddler on the Roof references. Which brings us back to musical theatre.

America seems a country divided, often by faith. There are the faithful and the secular. Your book seems about bridging that divide.

Well, my life is also about bridging that divide. I grew up in an observant Jewish home, and now I’m a secular atheist, so I can relate to both experiences firsthand. These divides exist on a sociological or demographic level, but that doesn’t really describe most people’s individual lives. I’m an atheist and so is my husband, so we share a set of beliefs, but our religious backgrounds are different – I’m Jewish and he’s Catholic. My brother and I grew up in the same house, but he’s a rabbi and I’m an atheist – we share a religious background but not a current set of beliefs. And even though I don’t go to synagogue or pray, I’m firmly connected to the Jewish community; I’ve worked for the Jewish press for the past decade, so I spend every day as a “full-time Jew.” There are all sorts of connections between the faithful and the secular in our families, in our communities. The trick is to get down to the personal level and see the things that broad demographics obscure.

What would you say your main influences as a writer are?

I was a journalist long before I started writing fiction, so my influences come from two very different fields. The journalist in me wants to know all the details, to make sure everything makes sense and to keep all the characters honest. The fiction writer in me wants the story to be fun, interesting and new.

If you’re really asking what writers I admire, that’s a long list. Edmund White, who writes frankly about being gay without shame, and Philip Roth, who writes hyperbolically about being Jewish with just the right amount of shame. Armistead Maupin, who writes concise dialogue better than anyone on the planet. Kurt Vonnegut, because he used humour in such a devious way. David Feinberg, for turning so much rage into so much fun. Michael Lowenthal, Aaron Hamburger, Christopher Bram . . . the list is long.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra