With some 30 books authored in as many years, including fiction, poetry, history, memoir and travel writing, George (formerly Douglas) Fetherling has surpassed the merely prolific. Since moving to Toronto from New York in 1966, he has built a reputation as something of a national literary treasure.

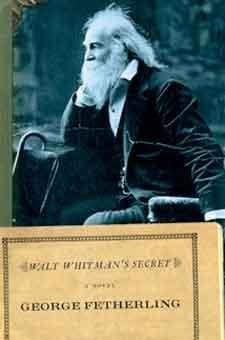

His third novel, Walt Whitman’s Secret, tackles the queerly avuncular American poet and proponent of male “adhesiveness,” as seen through the eyes of his platonic friend and literary secretary, Horace Traubel, author of With Walt Whitman in Camden.

In Fetherling’s update, Traubel’s multi-volume memoir of Whitman’s life and final illness is augmented by a private manuscript addressed to a “dear Flora” in Toronto: Canadian suffragist Flora MacDonald.

Early on, Traubel notes Whitman’s vehement response to critics who suggest his poetry celebrates immoral “Hellenic” notions of male bonding. Traubel sees a secret behind the vehemence, “but I long misunderstood just what the secret was.” We quickly get the more obvious secret out of the way. Traubel quotes Whitman telling of the night he was drawn to kiss a dying soldier in a Washington military hospital crammed with Civil War casualties. As biographers have noted, Whitman’s countless hours of volunteer care for wounded soldiers offered him some tender rewards.

Chapter Three introduces a new narrator writing from a century later – our present – with what seems at least equal affection for dear Walt. This scholarly fellow quickly gets to Pete Doyle, the most enduring of Whitman’s beaus, despite Doyle’s soldiering on the Confederate side and sharing at least one battle zone with Walt’s Union Army brother.

Fetherling’s images are often sharp, his phrasing sometimes subtly or tartly ironic. Here and there, he demonstrates the best use of historical fiction: it makes real what histories and biographies can’t. In the first bloom of their love, Pete asks Walt about an ex-boyfriend. “Was his robertson as good a thing as my own?” Walt replies by noting his experience bathing wounded soldiers, saying he’s likely seen more phalluses than most doctors, “some sweet and others sassy, none more outstanding than your own.”

One intriguing speculative fiction in the story is the friendship of Pete Doyle with the actor John Wilkes Booth, later to be Abraham Lincoln’s assassin. The two enjoy meals and, at one point, a male brothel together, while Doyle indulges Booth’s regular rants about politics.

Fetherling inserts swaths of Civil War–era history, stretching from the siege of Atlanta to petty border disputes with Canada. The unproductive historical asides tend to lead us far from dear old Walt. At its best, the prose can sometimes echo the brash American sweep of, say, E L Doctorow’s Ragtime, but mostly it impresses by how removed it is from Whitman and his life’s concerns, whether personal, literary or political. Why tell us about a cross-border skirmish in Vermont that sees a perpetrator saved from the gallows by a Montreal lawyer who went on to become Canada’s Prime Minister? Better are scenes with Walt’s mystical Canadian friend Maurice Bucke, famed proponent of “cosmic consciousness.”

Serious Whitman fans will have fun sorting fact from fiction. They’ll also be able to fill in missing continuity and backstory. Fetherling’s references to events and people in Whitman’s life (and especially to his works) often assume a larger knowledge in the reader. Those who know little about Whitman will struggle to connect the dots.

Things liven up with the plotting that ends in Booth’s assassination of Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre. Fetherling places an acquaintance of Whitman in the theatre audience to watch the bloody show, allowing us to guess why he’s there – might this be an element of Whitman’s secret?

Ultimately, the story is mostly a ramble through the self-absorbed drift of Traubel’s memories. Whitman is seen mainly in his final years, sick and often bedridden. Sixty pages from the end, Traubel seems to speak for the perhaps weary reader, acknowledging “the hope that as I approach the end of these hasty reminiscences, I am coming to the point of them as well.”

Like the real Walt, this one dies in his home in Camden, New Jersey. Fetherling groups family and friends around the bed, in what might almost be a scene from Dickens. The closing chapters outline Traubel’s decline. His long missive to Flora meets an unexpected fate, leaving only us and Flora to know the full truth about Walt and Pete and Horace Traubel.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra