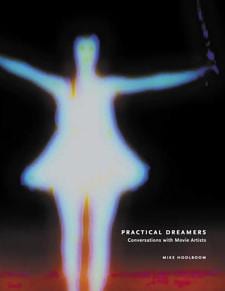

Mike Hoolboom has established himself over the past three decades as not only one of Canada’s greatest film artists, but as one of the most passionate and hard-working proselytizers and chroniclers of what he calls the “fringe” film/video movement. In the 21st century, if we go by Hoolboom’s massive new tome of interviews with dozens of artists and filmmakers, Practical Dreamers: Conversations with Movie Artists, fringe movies can cover everything from independent and avant-garde cinema to video, installation art and projector performances — pretty much any moving images that can be appreciated as art. A follow-up to his Inside the Pleasure Dome, this collection is an indispensable resource for anyone who wants to understand how artists from Richard Fung and Steve Reinke to Daniel Barrow think about their work. It gives much more insight into the artistic process than any Q&A or pat artist statement could, so it goes a long way toward bridging artist and audience who, as Daniel Cockburn points out here, come to an artwork from two opposite sides: the maker sees the intent, the audience the result.

For Hoolboom making pictures humbly and as an individual — rather than as part of a machine like Hollywood — is a political act. He is a romantic and a true believer heavily invested in the medium’s potential for greatness. His questions often contain extensive, very smart and thoughtful insights into the work under discussion, though his highly lyrical and mannered writing style may rub some the wrong way (his references too can occasionally be obscure). His enthusiasm and his subjectivity, particularly his highly philosophical take on cinema and mortality, inflects every word, the direction of every conversation.

Each conversation is given at least 10 large pages; the interviews are more in-depth and considered compared to what one typically reads. Hoolboom cares deeply about the politics and aesthetics of movies, and he respects everyone here enough to really push them. That means that subjects like ethics or the value of making work that will likely be seen only by a handful of people come up often. For example when bad boy Jubal Brown goes on the warpath, Hoolboom is not afraid to challenge his apolitical nihilism (though they ultimately get stuck in a kind of moral communication breakdown). Hoolboom is always asking why, and for who rather than what, when, how. Second, the conversations occurred back and forth by email, often over a lengthy span of time, which means that both interviewer and artists could carefully labour over every word.

By choosing this route, Hoolboom sacrifices spontaneity for rigour — and by extension the book addresses a specialized audience. There’s nothing wrong with that, it’s almost as if he is refusing to sell a dazzling personality to you — which is what most journalistic interviews seem to be aiming for — suggesting that the work should do the dazzling first.

The most valuable conversations illuminate both the work and the personality behind it, particularly of those artists whose accomplishments are underrecognized. It was great reading about the trajectories of Midi Onodera’s or Ho Tam’s careers, for example, as well as finally seeing a substantial text about Aleesa Cohene’s work. In general the book is a particular treat for Torontonians as there are so many precious bits of local history and lore inside.

A few of the interviews sometimes read like cut-and-paste descriptions of the artists’ work that they took from grant applications. That’s why Emily Vey Duke’s section is so fantastic: of everyone here, hers is the most unashamedly, openly emotional, which tempers the volume’s analytic tone. She is unafraid to discuss the messy feelings that others choose to leave out. Donigan Cumming’s work is so raw, enigmatic and troubling — up-close and very personal documents of his friendships with desperate and damaged people — that it is heartening to learn of the searching, restless intellect and profound empathy of the man behind the videos. (He argues that his subjects’ failures simply “are more spectacular than ours.”)

Considering the current media environment it would have been interesting to hear more of Hoolboom’s thoughts on the current relatively easy access to not just production but exhibition too in the form of YouTube and other video sharing communities that reach millions of viewers. At one point he suggests that the “portals” of exhibition remain closed, which seems a bit dated — more interesting would be to ask how the internet has affected access, rather than proclaiming the situation still as dire as it used to be.

All in all, however, an involving and substantial read and an essential research tool.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra