Kiran is in sixth grade in Cincinnati. His secret — he’s a girlie-boy — is getting harder and harder to keep. As his mother cooks basmati and lentils in their suburban kitchen, he’s upstairs with her makeup kit, smitten with the image of his dark eyes framed by mascara and blue eyeshadow. Caught in the act a moment later, he blurts an inspired defence to his devout mom: He’s Krishna, the blue-skinned Hindu god-prince, who just happens to be winking at him from his mother’s bedroom shrine.

The schoolyard reveals deeper desires. Two conniving girlfriends set out one day to trap Kiran with leading questions. “So, Key-ran,” says Melissa. “Who’s better, Malibu Barbie or Evening Gown Barbie?” His reply is instant: Gown trumps beach attire. “Her dress shimmers; her eyeshadow has silver glitter in it, so it gleams extra-specially… and she comes with a hot pink comb, which you can use to do your own hair.” They ask if he likes Ken. “A small bump forms in my sweatpants, like a creature rousing itself.” The girls want to examine the evidence. Sarah comes close and whispers with her “candy” breath, “You know Ken is missing something.” Just as Kiran’s stiffy is about to be exposed he’s saved by a mishap involving his buttcheek and a large splinter — and we’re off for an embarrassing visit to the school nurse.

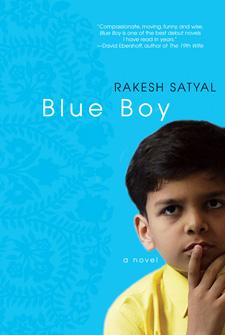

At what point does the gentle amusement spurred by this sort of writing start to morph into a desire for more substance? I guess that depends on the reader in question. Twenty pages into Rakesh Satyal’s first novel I was already getting twitchy, but chapter two helped to keep the restless yawns at bay. We join Kiran on the family’s weekly temple visit, where the Hindu rituals and iconography make an arresting backdrop. What really makes his spirit soar is the lad he sits behind, “the dreamy Ashok Gupta.” At 12, Ashok is already “a total hunk” with a perfect beauty spot on the smooth skin of his neck.

As the prospect of homo puppy love emerges, Kiran backtracks somewhat with a sporty friend who introduces him to Playboy magazine. The luscious nipples and breasts mesmerize Kiran — until the shot featuring a rock-hard sausage approaching a waiting apple strudel. But all he really wants is the meat. Unaccountable digressions ensue. Krishna had a thing about butter, so a 10-page chapter is devoted to hoarding and secretly eating Country Crock margarine. Kiran’s dad finally pitches it in the garbage, along with his beloved Blueberry Muffin doll.

Kiran has a fantasy that he is the long-awaited 10th incarnation of Krishna. “I have spent so much time looking at my face in the mirror… the roundness of my eyes, the whites so visible all around… my cute button of a nose. My high cheekbones.” He spends hours studying Eastern religion in the public library, where “jubilant light” from its windows illuminates his budding messiah complex. His drawings of Krishna are promoted by his school’s Jewish art teacher for a hallway display, but are rejected. Board policy forbids the assigning or displaying of religious artwork. Here Satyal offers glimpses of some thematic oomph. When does suppression of religious expression become denial of culture? We also begin to see the shadows in this family: a mom who’s essentially a house slave, suppressing her unhappiness, a father whose preoccupations are absurd penny-pinching and pedantic authority. The house is full of tensions. Kiran is the jester who must tread carefully, hoping the tradition-bound parents will lighten up.

Kiran still being only 12 when the story ends, this is finally not a coming-of-age story but more an episodic sketch of a boy who has embraced his inner femme and his artistic heritage, yet has only barely begun to negotiate the erotic side of the equation. I found it disappointing that Satyal didn’t take us further. Kiran is a snapshot character, colourful and diverting but viewed for only a few months of childhood. After 200-plus pages, he’s still pretty much the stumbling-seeking kid he was at the start.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra