The evening is warm, the party has gone late. How warm, how late: it’s hard to say. Enough that the window is cracked open, a black square of night visible beyond it. Warm enough and late enough that everyone is on the floor. Two people lie side by side, knees bent beneath them. In the corner, someone’s on their back, fingers wrapped around a glass beer bottle. It’s hard, in the photograph, to say where one body ends and another begins. Yes, we are at that point in the party. An empty pack of cigarettes lies stranded toward the bottom of the frame, its smoke gone somewhere out the window and into the night.

When I first saw this image—the 2008 photograph Birthday Party by the German artist Wolfgang Tillmans—it was a small printout, taped to the wall of the co-operative house in Boston where I lived for my last year of college. I mistook it, at first, for a photo taken in that house. It was an easy mistake to make. How many times had I seen a scene like this—of sticky wine and smoke and uncomplicated touch from all sides—happen here? Countless. They blurred together in my mind. Seeing Tillmans’ photo, these moments shuffled into focus with uncanny clarity. It was like coming across a high-definition rendering of a faded memory: a memory that was not mine, of course, but that felt, somehow, like it was.

The photo hangs now at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), where Tillmans’ exhibit To look without fear—the first major showing of the photographer’s work in Canada—opens this month. To look without fear arrives after its debut at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) last fall, drawing together images from across three decades of the artist’s career. Dispatches from ’90s queer clubs in Berlin and London sit beside abstract compositions of form and colour across from still lifes of flowers and lobsters. Together, these assembled works ask for a certain way of looking, one suggested by the exhibit’s infinitive title. Describing what motivates him to capture a moment, Tillmans has remarked: “I want to record it, so there is a record of it.” His record urges the viewer to remember places and intimacies and pleasures that might otherwise blur into the past—out of focus, out of view.

Credit: Wolfgang Tillmans

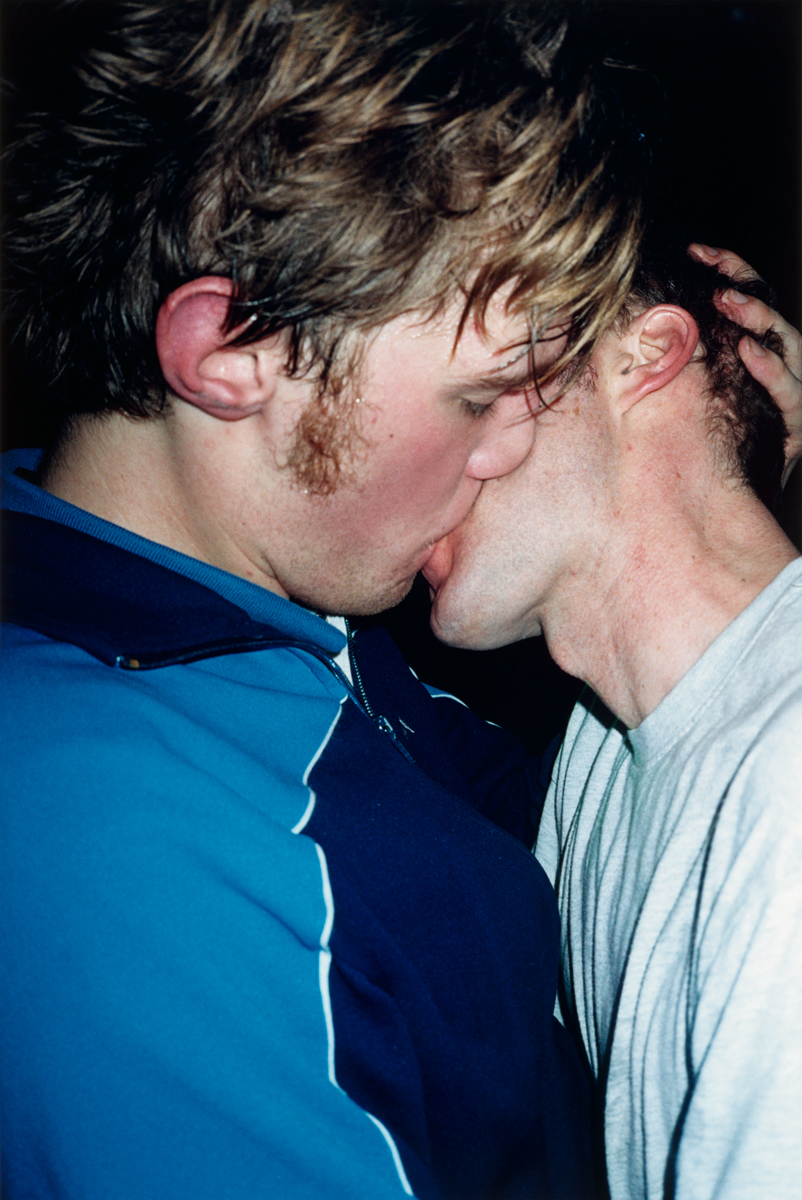

Even if the name Wolfgang Tillmans is unfamiliar, there’s a good chance that you’ve seen his work. In 2017, Tillmans’ portrait of Frank Ocean, titled Frank, in the shower, appeared on the cover of Ocean’s acclaimed album Blonde. In the photo, Ocean’s hand obscures his face, green buzzcut peeking out above. Last year Tillman’s work surfaced in bookstores when The Cock (kiss)—a photo of two men, well, kissing—was featured on the cover of the novel Young Mungo by Douglas Stuart. These ongoing circulations of Tillmans’ photography are both a testament to his wide-ranging influence on our visual culture (he’s been called “one of the world’s most significant living artists” by the New York Times), as well as a barometer of his continuing influence on queer artists across forms.

Tillmans was born in 1969 in the small German manufacturing town of Remscheid. As a teenager, Tillmans would catch the train into London—ostensibly to take English classes, which he did, but also to put on lipstick in the train station and try his luck at the city’s gay nightclubs, getting back on the train home before midnight. One of his earliest photographs that he considers a work of art is a self-portrait from 1986, Lacanau (Self). Tillmans holds the camera from above, angling it down at his body. What we see is a wide swath of pink T-shirt, his leg barely separated from the ground beneath it. It’s both hyper-realist and willfully abstract, charged with the youthful exertion of a body feeling out its proportional space in the world.

Tillmans photography has gone on to consider that question of how to render, in two dimensions, the three-dimensional problem of the human body—its constraints and liberations, its sculptural possibilities. He’s an attentive and accomplished portraitist in the fashion world, whose photos of Kate Moss and Chloë Sevigny appear in To look without fear. But the body really comes alive, under Tillmans’ lens, in scenes of proximity and obscurity—in nightclubs and house parties, bathrooms and bedrooms. “I want to capture the community of being together,” Tillmans explains during a preview of the AGO show, “as a couple, as friends, as a group, as a mass. Sharing this togetherness is also always sharing solidarity, shouldering and appreciating the hardship and joy of what it means to be alive.”

In the 1990s, Tillmans started to create a growing body of these images when he left Germany to study photography in the U.K. He’d tried his hand at art school back home, but dropped out after six weeks—one day before the Berlin Wall fell. In England, Tillmans stuck with it, producing lasting works of, as he puts it, “guys and girls feeling each other on the dance floor.” One 1992 series titled Chemistry Squares depicts scenes at Chemistry, a house and techno night at the now-defunct Sound Shaft club in London. (As a rule, Tillmans does not display images of underground spaces or parties until they have closed down.) The dozens of images are just glimpses—each a small square of detail, a couple inches wide, displayed side by side—as if caught between strobe lights on the dancefloor. A hand with a cigarette. A back of a neck. A flash of hair beneath a raised arm.

As a “record” of those evenings, the photographs leave much unsaid. We have no sense of what Chemistry looked like, who was in attendance, how much it cost to get in. Tillmans’ photos are evocative, however, as coordinates to the heat map of that night, witnessed from up close. The camera knows—and so tells us—how one person saw another, the facts of skin that formed the bodies that formed the crowd. Perhaps, the photos suggest, you must get this close to understand what it was really like to be there. So close that now, decades after the club has closed, sweat still collects on a neck beneath the lights.

Credit: Wolfgang Tillmans

At the AGO artist preview, Tillmans, wearing a green jacket from ’90s-influenced streetwear brand Palace, passes through the gallery rooms while discussing the past few days. He’s been busy. In collaboration with his team and the museum, the artist has adapted his MoMA exhibit specifically for the AGO space. Pieces have been resized, rearranged. Today, a week out from the exhibit’s opening, Tillmans is focused and deliberative, but never serious. His smile flashes often. At one point, Tillmans indicates a pair of metal beams where two images are affixed. “These beams interested me,” he says, “because they are 12 inches—the size of the prints I’ve been using since the early ’90s.” He smiles again. “I’m like a child when he realizes something fits.”

As has become standard for Tillmans’ exhibits, most photos in To look without fear are displayed without frames. Instead, the artist uses Scotch Tape or binder clips to hang his images. It’s an improvised, offhand aesthetic that belies its careful planning, orchestrated down to the inch. The exhibit, arranged in roughly chronological order, forces you to use your body—leaning back to see one photo, bending down to see the next. When the MoMA show premiered last fall, critics and viewers alike talked about that sense of scale, with scenes of the past surrounding you from all directions. Crowded raves and old Pride parades. Adidas tracksuits and clunky bass synthesizers. One reviewer confessed: “The show made me so nostalgic that at times, I wanted to crouch down and weep.”

Credit: Wolfgang Tillmans

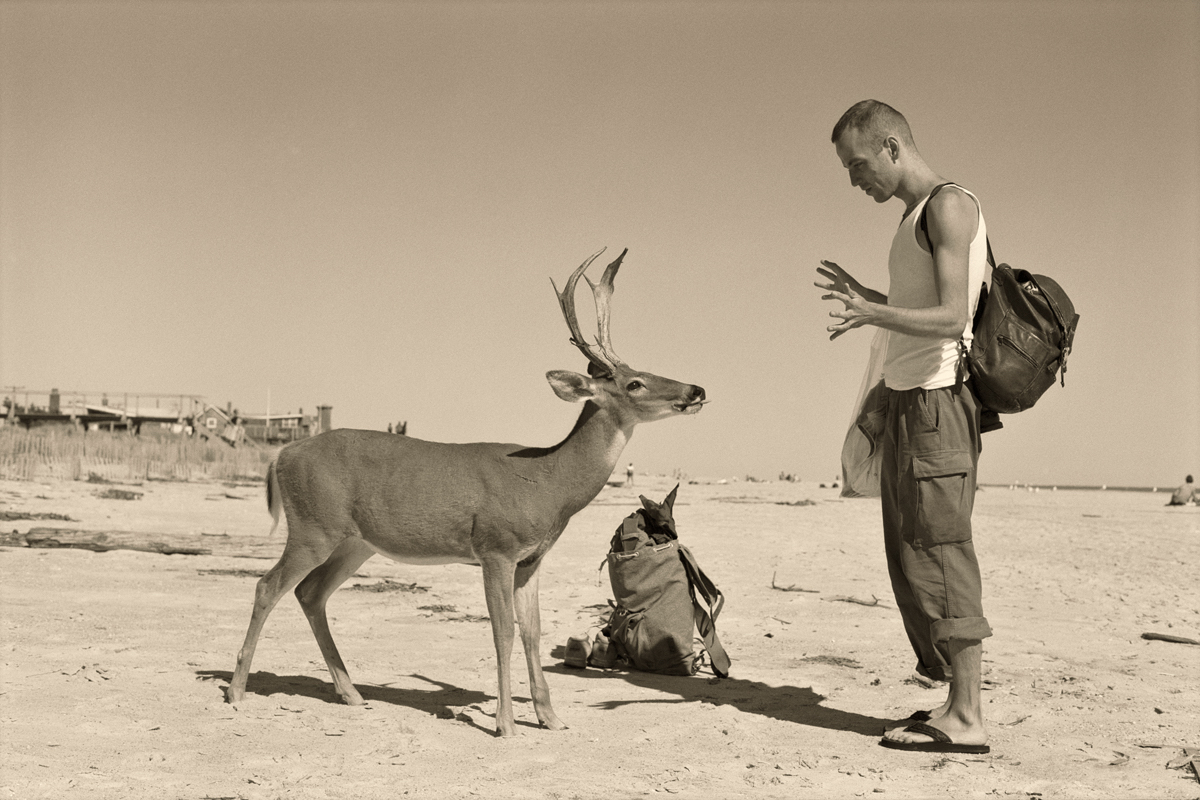

But there’s more than easy nostalgia at work here. History, in these rooms, is too unresolved, too particular to Tillmans’ life. Halfway through the first room, I come across a large sepia image from 1995 titled Deer Hirsch. In it, Jochen Hirsch—Tillmans’ first love, who passed of AIDS-related pneumonia two years after the photo was taken—stands facing a deer on a wide beach. Hirsch’s hands are raised, indicating he has no more food to give. The deer sticks out its tongue in reply. “The photo looks like it was a big production,” Tillmans admits, “but in fact it was just an afternoon walk. What you are seeing is that Jochen had just fed all our food to the deer.” There’s such suspended tenderness in the image that I hesitated to speak when near it—out of reverence for having stepped into Tillmans’ memory, out of care not to startle the animal away.

For Tillmans, the past is unresolved, particular—and alive. In a final room containing work from the current millennium, the artist shifts the scale of his archival eye. Several tables fill the large space, each one covered with fragments of text. There are newspaper articles about the Iraq war. There are think pieces about the rise of homophobia and nationalism. There are scientific reports on microplastics in the human body. It’s part of the series titled truth study center, a collection of media sources that construct the reality according to which our lives are governed. On the surrounding walls, the exhibit assembles photos we might think of as archetypal Tillmans: a hand reaching into a pair of red gym shorts, a queer club in New York. The tables sit below, gazing up, as reminders of the operations of power that run always beneath these intimate scenes. (When I say always, I mean it: I was surprised to find an article discussing caste discrimination in the Toronto school system, dated just two weeks prior.)

Credit: Wolfgang Tillmans

“History is not something other,” Tillmans explains. “History is right here and now, and we have to take care of this moment.” Keeping a record of our moment, for Tillmans, still involves capturing the shared choreographies of “being together.” Yet he also acts, increasingly, as a custodian of large-scale power structures that define past and present. In all of these roles, Tillmans is engaged in a practice that asks us to look at—and then remember—what is at risk of going unseen. Something so small it escapes notice: a splinter in the foot, a touch in a crowded club. Something so big it evades depiction: beliefs we take for granted, invisible as air, about the way things must be.

Looking up from the tables, I notice, in a far corner, Birthday Party—the same photo of a warm evening years ago that hangs in a house where I once lived. Or, almost the same one. Tillmans considers each print of his to be a distinct physical fact, defined by its material quality and where it is placed in the world. Again pointing out something I hadn’t noticed, he indicates the thin shadow cast between image and wall. “Looking sideways, we can see that this is not nothing. A photograph is actually a body.” I turn around and take in the crowded gallery walls, dozens of images and their shadows filling the room. As Tillmans walks ahead, quick enough that some air displaces around him, you could swear—for a moment—the photos behind him begin to move.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra