“‘You keep getting into these fucked-up relationships,’ my brother said. ‘Does this have anything to do with that guy in Toronto?’”

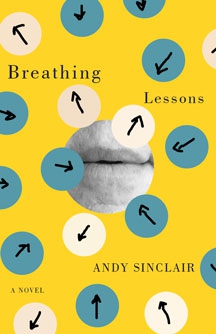

It’s one question that looms large throughout Breathing Lessons, the debut novel from Andy Sinclair. Its everyman hero Henry Moss notes that the Toronto locale of one powerful memory has been turned into a giant hole for a new condo tower. “I could peer in,” he says, “but I couldn’t see the bottom.”

Though the 20 vignettes that make up this novel are tagged as “lessons,” anyone looking for easy answers, simple morals or even a tidy narrative will remain frustrated. The messy, sexy contents of Henry’s life and mind are as frustratingly opaque to us as they are to him, while the parade of lovers, boyfriends and tricks gets hard to sort out. Which one was Brian again? Maybe even Henry doesn’t know, as at one point he thinks, “I should be enjoying this. I thought it was all I wanted.”

Though the 20 vignettes that make up this novel are tagged as “lessons,” anyone looking for easy answers, simple morals or even a tidy narrative will remain frustrated. The messy, sexy contents of Henry’s life and mind are as frustratingly opaque to us as they are to him, while the parade of lovers, boyfriends and tricks gets hard to sort out. Which one was Brian again? Maybe even Henry doesn’t know, as at one point he thinks, “I should be enjoying this. I thought it was all I wanted.”

In examining Henry’s struggle to find love, Sinclair digs deep, sometimes painfully, but these lessons will resonate with anyone who’s ever stood waiting at a bar, phone in hand, scrolling through Grindr.

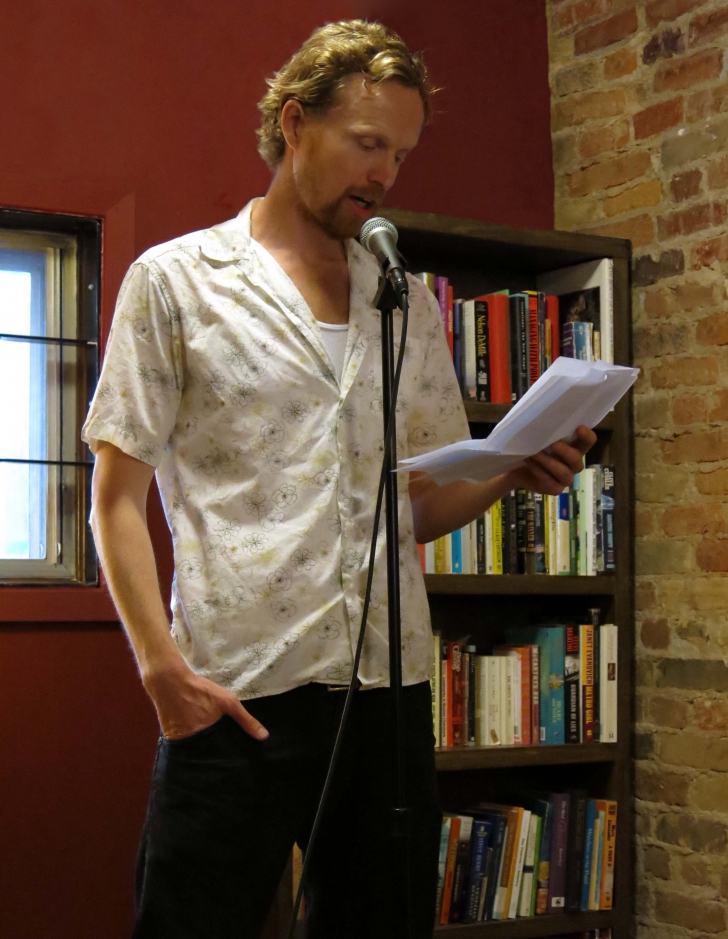

Any first novelist, especially one writing anything personal, will be asked just how autobiographical their tales are, so when talking to Sinclair, I got that out of the way first:

“I used autobiographical elements and hyperbolized them,” Sinclair says, “Henry is gay and from a small city up north, same as me. Many of the things that have happened to him have happened to me; some have not. I borrowed on friends’ experiences, and made some stories up completely. I used to think like Henry, but in writing about him I was able to really differentiate myself from him.”

As the book hopscotches around the timeline of Henry’s life, so many people drift in and out. Sinclair doesn’t seem to play favourites, though he laughs, “Henry has a backpacking buddy, Beth, who is compassionate towards him and at the same time isn’t going to let him interfere with her Scandinavian sexual adventures. Those are two qualities I admire in a person.”

What’s exciting about reading Henry’s travails is how relatable they can be. His evenings are as sexy, as sad, as awkward as any that any of us did, or will, experience in our thirties. As uncomfortable as some moments are to read, were there any too uncomfortable for the author to reveal?

“I try to write openly,” Sinclair says, “I think writing about the ugly aspects of Henry’s character and activities was good practice for writing about broader things that can be intimidating to reveal, such as less-popular political viewpoints.

“I try to write openly,” Sinclair says, “I think writing about the ugly aspects of Henry’s character and activities was good practice for writing about broader things that can be intimidating to reveal, such as less-popular political viewpoints.

“The stories are fun to tell,” Henry says the reader, describing “the lucky details from my Saturday night . . . I don’t embellish and I don’t hold back.” The book’s mix of sexual frankness and urban melancholy recalls classic gay novels like Dancer From The Dance, though Sinclair disagrees with any talk of pre- or post-AIDS eras.

“No. I don’t think anybody who came of age in the 1980s will ever look at sex as innocently. Larry Kramer in The Tragedy of Today’s Gays talks about how those in charge looked the other way at the start of the AIDS era instead of doing anything about it. And I like to think that we are strengthening our vigilance now, in all aspects.”

Is Henry’s promiscuity the ultimate expression of the freedom queer people fought for? Or the result of deep dysfunction or immaturity? An easy answer either way won’t be found in these pages and it’s Sinclair’s lack of judgment that makes the book compelling. Unlike our carefully manicured Facebook pages, Henry is allowed to be complicated. He, like any of us, obviously has emotional needs yet struggles because he can never, ever appear “needy.”

“I think being open and honest about what you want and what you need can be a sign of strength,” Sinclair says, “And yes, some people who are very closed are also incredibly sexy but how much are we projecting onto those blank slates?”

That’s another question that looms large in the book, as Henry chases more than one emotionally unavailable man and Sinclair raises questions about fidelity, honesty and what makes for successful cruising.

“Speaking of the 1970s,” Sinclair asks, “can you imagine how wonderfully alert and attuned you’d have to be to pick someone up solely on the basis of quickly exchanged glances? I think we have no idea what we are losing in the Grindr era. And yes, that’s coming partly from someone who feels that he is approaching adaptation failure in regards to new technology. I was cycling around the other day and saw some dudes in their 60s and 70s listening to Walkmans, and I thought, yes, that’s about right. They must have reached a point where they felt they had better things to do than keep up with all of that stuff.”

Is that “the point” after this 20-lesson plan? To let go and just breathe? Sinclair has no definite answer, only ever more provocative questions.

Breathing Lessons is available through Véhicule Press.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra