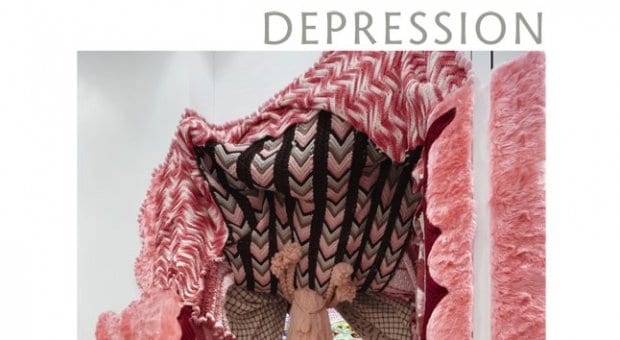

Ann Cvetkovich in a production still from a short film called The Alphabet of Feeling Bad, by Karin Michalski Credit: Karin Michalski

BC-born and raised Ann Cvetkovich teaches English and women’s studies at the University of Texas in Austin. Her latest book, Depression: A Public Feeling, has been widely discussed as a remarkable contribution to understanding depression not as a chemical imbalance or a personal problem, but as embedded in and produced by the societies and political systems we live in. In one chapter, Cvetkovich discards the scholarly methodology in favour of a personal essay on how she found ways out of depression. We recently spoke about the book on Skype.

Many people insist that the pharmaceutical model works and that the meds help them. The depressed often don’t want to look at the root causes; they want immediate relief. Thoughts?

It’s a delicate issue. In talking to people face-to-face, I try to give as much space as possible for their perceptions, their experiences and their choices and to present mine as just another way of looking at what is obviously a very complicated phenomenon.

But it does seem to me like there’s a considerable groundswell of more medically focused critiques of pharmaceuticals in the media. I wonder if there’s going to be a tipping point where there will be, even among the medical establishment, an acknowledgment of the limits of the pharmaceuticals. Although again, I would still be open to whatever the statistics show about people’s individual experience of being helped by them . . . There are multiple ways in which pharmaceuticals might help people. They literally help them because they change their physical chemistry, and then they help in a more conceptual way, by giving a name for what people are experiencing.

On a deeper level, yes, I do want to challenge people to consider the ways in which that medical model and the forms of treatment that it provides might be somewhat limited. Perhaps analogous to what happens for addicts when they actually stop using whatever substance it is that is messing them up. The real journey begins at the moment when you get clean and sober and have to ask yourself why you were an addict in the first place. And with regards to depression, many people say they needed the drugs to jump-start a process of becoming more functional. Once they are more functional, people are still at a crossroads about what they’re going to do both with their own lives and the larger world out there.

Is depression a middle-class disease? Are there any studies about its socioeconomic side?

I try to grapple in the book with the way in which a particular kind of depression is emphatically middle class and to give some attention to that: to say, well, what’s going on that even people of relative privilege are experiencing tremendous senses of dysfunctionality, sadness and confusion. Then there’s also the question of what would happen if we focused on other groups. And I think that there are many people who live with a tremendous degree of oppression and manage to sort out modes of survival that are part of how one gets by as a working-class person or a person of colour. That may not get called depression, because it’s just survival, it’s how people get by. There are certain forms of built-in hopelessness as well as certain ways of surviving through different kinds of cultures of pleasures.

It would be good to look more closely at the modes of survival that people have figured out like this that don’t come into contact with the medical establishment. But if there are studies, they would probably presume a certain social-service model where the goal is to bring people into the care and attention of the state and the helping professions. My book’s interest is in more non-medical and more cultural and sociological kinds of approaches. I’m interested in coming up with an everyday politics of the body, where we really focus in on what kinds of modes of survival may enable people to live -– in the same way drugs seem to be working with some people, they give them a kind of limited functionality. What are other ways in which we can cultivate the resources that we need in order to be as resilient or vital as possible in our daily lives, under the conditions of rampant capitalism, rampant militarism, social conflicts of various kinds.

Your depression diary in the book is very frank, but you remove from it the dating life almost completely. Can we abstract out the love life from the causes of unhappiness?

I try to indicate that certainly love was one of the things that saved me, but I didn’t want to put too simple a spin on it, like “Find a partner and everything will be okay,” especially because of my interest in queer relations. It’s not just an individual relation that will save you, though provisionally under capitalism and the way the social relations are structured today, I think that love partnerships are one of the ways in which people most efficiently try to sustain themselves.

I felt there was a story I wanted to tell about my creative struggle that was of the more solo nature. I don’t think I would have been ready to be in a successful relationship had I not come to a kind of reckoning with my own sense of value or commitment to the world. For me as a scholar and artist, that was through my relation to ideas and writing. So part of the story is specific to people who identify with those categories, but if pushed, I’d also suggest that is something every person has to do: find some relation to a kind of broad notion of creativity. I think that’s something that everyone needs to do. I am also very populist in the sense I don’t believe in the elite category of artist. I think everyone is creative: people who work with their hands in the kitchen, or building houses, or play an instrument in addition to whatever else they do in life . . . those are ways of building vitality and creativity.

Have you ever tried psychoanalysis?

Personally, I haven’t done straight-up Freudian analysis but am certainly interested . . . I have not seen a therapist for a very long time, partly because my chosen form of therapy is co-counselling, which is a collective-based peer-counselling practice connected to liberation theory. It is the kind of therapy that doesn’t rely on professional training, so people get to be human with each other, and we also get to work on race, class, gender, religion, artist identity, environmentalism . . . it’s a very politicized sense of how therapy works. I get to be a counsellor as well as a client. Basically, it’s a process of just giving attention to another person, fully attending to or witnessing someone else’s struggle. I had some really amazing experiences in relation to other people’s psychic work, and this has profoundly influenced my work.

How come you chose all the femme-y crafts in your chapter on arts? Where is welding? Where is carpentry?

A similar question came up at a recent conference in Glasgow, with Jack Halberstam, who’s my constant interlocutor. Jack was like, “There’s a lot of pussy in this book.” I seem to have gravitated towards these femme-y examples of craftwork, and it’s probably because I want to make space for a kind of pussy-work that is often stigmatized. You know the attitude: Oh, forget about Home Economics — I’m going to go to Shop and be one of those women who weld and saw. And it’s important to have women in a world heavily dominated by men. But it’s also important to be able to continue to embrace the really femme-y craft as well. We want to go in both directions, make it possible to embrace a masculine world that’s often been foreclosed to women and to embrace this too-cloying, pink world of the pussy that feminists can also disavow. It’s a very personal book, and I’ve come to my objects through a very slow process of accretion and of finding things that appeal to me, and then tried to explain to myself and for other people why they may be of interest. That’s also not only a queer method — maybe more of a femme method: “Here’s my stuff that I like . . . you don’t have to like them, too, but maybe you can show me something else that you like.”

Depression: A Public Feeling

Available at Glad Day Bookshop

598 Yonge St

gladdaybookshop.com

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra