Recently, I talked to an 18-year-old gay male who said he wished that he was HIV-positive so he could belong.

This young man hadn’t been out very long and was new to the city and was trying to find a place to fit in as a gay man. When he looked around the community, he saw HIV-positive gay men forming groups and bonding and developing their identities. He felt that if he seroconverted there would be a place for him to belong – with these men.

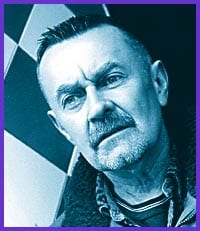

I also recently talked to a 48-year-old man at the baths who no longer practices safer sex.

He told me that he has remained uninfected for 18 years, so he must be immune. Going deeper into conversation with him, he revealed that most of his gay male friends had died and that the gay community that he had felt a part of for so long has disappeared. What has replaced it for him is a community that is not welcoming to him, that often discounts him as invisible simply because he is no longer young.

He felt isolated except when he went to the baths. And because he has given up on the community, he finds it hard to see a future for himself and hence is more willing to take risks in order to fulfill his need for intimacy and sex with other men.

We have all heard the reports on the rise of HIV infections in gay men. In fact, rates in Toronto may have doubled.

Some people have called this the second wave.

And how have our AIDS organizations responded to this alarming news? Charles Roy, executive director of the AIDS Committee Of Toronto (ACT), has said that he knows that something deeper is going on, but he doesn’t know what it is. ACT’s Lee Zaslofsky has said that staff don’t know what to do about rising infections in gay men.

The people being paid to handle AIDS prevention efforts for the majority of gay men in Toronto have run out of ideas.

We cannot keep on the current path.

Yet all of this is not news to me. I was a volunteer group facilitator for ACT back in 1997. I facilitated groups for HIV-negative gay men. As uninfected gay men, we never really felt welcome at 399 Church St. We used a meeting room on the second floor, and I put up a sign on the main floor inside the entrance on the first night: “HIV-negative gay men’s group – go to the second floor.”

The sign disappeared shortly after. I went up to the ACT offices to ask someone what had happened. A man at reception said to me, “We took it down. It offended some of ACT’s clients.”

But he didn’t tell me how.

The empowerment of PHAs back in the late 1980s was an important step, allowing people with HIV and AIDS to run their own show.

But then prevention took a back seat.

The actual word – “prevention” – even disappeared from much of ACT’s literature and even from its mission statement.

Prevention was replaced with the word “education.” The problem is that they are not the same thing. Prevention is more complex and more labour intensive. Education is a relatively easy to do.

And the problem, in my opinion, is that ACT has not had a new prevention idea in 15 years.

Bar outreach involves one man walking up to you late at night in a bar and handing you a condom and then running away. The bathhouse project has one man sitting in a room with clothes on, waiting for someone to walk into that room and talk to him about AIDS. There is no advertising and no announcement. Most men just walk by the room with no idea why he’s there.

ACT also has GMEN (Gay Men’s Education Network). It was formed several years ago to attempt to address prevention issues, but ACT’s contribution is one paid staff person.

The other members of GMEN are from culturally diverse groups who focus on their own specific target populations. But GMEN is far too low profile.

How many gay men have even heard of GMEN? I have only seen one two times in the last year, and I recognized him as one of the GMEN only because I know who he is. It is just not good enough.

ACT has a few other programs targeted at HIV-negative gay men, such as the One Night Stand groups.

I attended one. It was facilitated by an angry HIV-positive gay man who announced his status at the beginning of the evening in a tone of voice that sounded to me like a threat. I silently screamed, “They just don’t get it.”

It was a very disappointing evening. How could we discuss our concerns and fears about the disease in front of a man who had the disease and was also the leader of the group?

Surely part of the problem is burn out, or AIDS overload. There’s no shame in that.

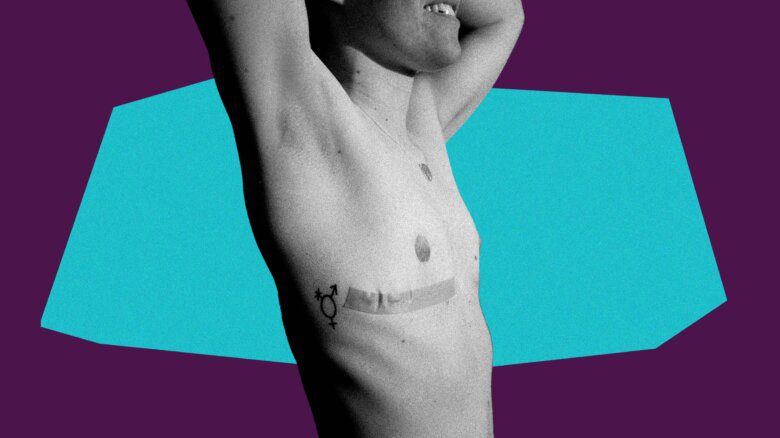

But now it is time for some new blood with new ideas and new programs created and run by gay men who are HIV-negative. The bottom line is that AIDS prevention must be removed from a culture where the rights of people with AIDS supersede the issues of uninfected gay men.

Prevention programs for gay men must operate at a distance from organizations staffed mainly by people who already have the disease. We need a major shake.

Firstly, we do not need two organizations to service people with HIV/AIDS. These services could easily come under one group. Presently we have the Toronto People With AIDS Foundation and we have ACT. Merging these two groups would be cost effective and there would be no duplication of services.

And the funding left over could be used to establish a new gay men’s health organization.

Prevention efforts could thrive. And under a new name that incorporates risk reduction and safer sex into the larger picture of gay men’s health, we could once again engage uninfected gay men who have needs that relate to their whole lives and not simply to AIDS.

Prevention has to come from a place of passion for the survival of the gay male community, and not from a place of resentment, as it too often has.

I can remember a time a few years ago when I felt guilty taking up my doctor’s time if there were men with HIV and AIDS in the waiting room. That guilt is harmful to me personally in other ways – including how I feel about my health, my sexual practices, my future and my survival.

For a long time, gay men were afraid to tell people that they were HIV-negative. They may have felt that this sounded like they were bragging or it may have ended a conversation. More guilt, and it is that guilt that may put some of us at risk.

Where are the stories of gay men who have lived through the past 18 years of AIDS and have managed to remain uninfected and sane? We are invisible.

Yes, what is needed now is a whole new gay men’s health initiative with a mandate that addresses drug and alcohol abuse, isolation, sexual addiction, coming out, aging, body image issues, spirituality, and a range of health issues that run from exercise to diet to reducing our risk for HIV infection. When we have this kind of organization in Toronto, gay men will reconnect with a healthy movement and with their own community. This is where HIV prevention efforts will succeed in the future.

(The initial focus would be for HIV-negative men’s health, but ultimately we would work towards reconnecting with the AIDS organization to work together to meet the needs of all gay men, negative and positive.)

We have an incredible group in Toronto for older gay men called Prime Timers. This group fills a real need, but it attracts mostly men 55 years and up, and mainly men who are retired. What is needed now is a social group for men 35 to 55 years old. A group where gay men can talk about losing their youth, about changes in their body, about losing their friends and relationship issues. A group that embraces the transition from being young to being middle aged. In my 50s now myself, I feel younger in many ways than I have in a long time. But that didn’t come without work, and many men need help and support in this important transition.

And this is now the group with the highest rates of new infections.

These men work and go to the gym but many of them have nowhere to really talk to other gay men in their age group unless they go somewhere like a gay church or sports league. The bars lose their allure for many men at this age. Gay bars are mostly not welcoming to older men who still attend. Some feel they have nowhere to go to be around other gay men.

I was at the baths a couple of weeks ago. I met an incredible 40-year-old man named Frank. It started out as a sexual attraction but once inside my room and after a certain amount of physical activity, a sense of intimacy was created and we started to talk.

We talked about isolation, turning 40 and about some of our basic needs and how or if they were being met. At some point we left the room to shower and get a drink of water and when I opened the door to my room, there was a circle of men in towels outside who were listening to our conversation.

It was a startling realization for me. Many gay men are needing conversation and the joy of listening to other gay men’s stories. Sharing our stories like this is definitely one way that the HIV prevention efforts will succeed in the future.

We don’t need a man handing us a condom in a bar at midnight on a Friday night. We need workshops and drop-ins away from ACT, that are facilitated by uninfected gay men.

We need uninfected gay male lay counsellors who are not part of any AIDS organization to help other gay men with life issues and with their concerns around sex.

And we should adopt programs that have worked well in other cities such as San Francisco’s Stop AIDS Project. The project was started in 1985 and stopped in 1990; it’s been resurrected because HIV rates are up – and because it was so successful.

Stop AIDS is run by gay men in their own community. Small groups of gay men are recruited right off the street and are invited to small house parties, safe private spaces with a facilitator where gay men have the opportunity to open up and talk and ask questions and, maybe most importantly, listen to other men’s stories about how they are living their lives.

It all sounds so simple – but it will take work and commitment to make it happen. We need to start promoting the values of remaining HIV-negative and paint pictures for men of a future with a healthy and vibrant gay men’s culture and community.

We need to inspire those men who have been active in the community in the past to bring them back to join us.

These are some of the ways that prevention efforts will pay off in the future. There’s no guarantee any of this will work. But we have to try. It’s time we started feeling really good and really proud about being gay men again.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra