I’ve been thinking lately about an Instagram post of an old issue of the New York Times from January 1991, when the AIDS death toll reached 100,000: a small paragraph on page 18 full of other stories, the names of those who had died nowhere to be found. The post first made its rounds on my friends’ Instagram stories this May, highlighting the differences between the coverage of the AIDS crisis and coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic. After the novel coronavirus took the lives of 100,000 people, the New York Times put their names on the front page—a living memorial to lives lost.

Comparing these two diseases might seem strange, or even unnecessary. But it’s something that’s popped up with regularity since the start of the pandemic. Political websites and newsletters often make the comparison: In March, Politico writer Sarah Wheaton drew parallels between the two by noting the ways in which young people respond to each of the virus’ threats. In an essay for the culture magazine PopMatters, writer Timothy Barnett calls into reflection Tony Kushner’s seminal play Angels in America and how Donald Trump’s America has tackled COVID-19. And in the New York Times, Michele C. Hollow points to HIV testing in the adult film industry for lessons when it comes to creating models to test for COVID-19.

While some of these stories might have a certain resonance, a comparison that’s strictly about infection and illness glosses over what made the AIDS crisis seemingly impossible to deal with for those who were infected with the disease: That COVID-19 and HIV/AIDS are both global public health crises isn’t enough to make them comparable in a meaningful way.

The duality in the New York Times’ approaches to the morbid milestone of 100,000 COVID-19-related deaths is a microcosm of these differences. In the case of the novel coronavirus, solidarity was invoked; the idea that we’re all in this together and only by coming together as a global community are we able to stop the spread of a deadly virus. With AIDS, however, there was little to no desire in the press to even report on what was happening; Ronald Reagan’s White House infamously seemed to treat the beginning of the crisis as a kind joke after hearing it described as “gay plague,” to say nothing of the political silence that came to define the response to the epidemic.

And the comparison that might actually hold some weight—that both diseases disproportionately affect those from minority groups—is something that governments have been slow to acknowledge. In the U.K., a report on COVID-19’s effects on minority communities came only in the wake of increasing political pressure against the government. Despite reports that Black people are four times more likely to die from COVID-19 and that lower-income people and immigrants are disproportionately affected by the virus, political responses to COVID-19 are defined by a sense of solidarity: we are one and the same in fighting this pandemic. Governments the world over are offering people support, helping to pay wages as companies and industries slow down, halt or implode; offering relief on mortgages (but not on rents). This creates the illusion that we’re all in this together—even if some of us are more at risk than others.

The AIDS crisis, however, was defined by shame and the continued marginalization of those who were most in need of help from the government. It’s impossible to think of media responses to the AIDS crisis without evoking the story William Buckley Jr., an American author who suggested that people who had AIDS should be tattooed—not unlike those in concentration camps—so that everyone knew their status. To treat these two diseases as being the same ignores how queer communities fought back against these narratives of silence and shame and their stigmatization.

“To treat these two diseases as being the same ignores how queer communities fought back against these narratives of silence and shame and their stigmatization”

Much of the writing that came from, and went on to define the AIDS crisis, reads as a challenge to this silence, a refusal to let narratives ignored by the establishment be consigned to history without a second glance. Often straddling the line between the personal and the political, the work of writers like Larry Kramer, Andrew Holleran and David Wojnarowicz are at once a cry against an establishment that doesn’t care and a desperate attempt to memorialize a world that’s disappearing all too quickly. One of the most striking images in Holleran’s Chronicle of a Plague, Revisited: AIDS and Its Aftermath, a series of essays written during the epidemic as Holleran’s friends were dying and there was silence outside of his community, is a snapshot of what it was like to live in New York at the time: “Like attending a dinner party at which some of the guests were being taken outside and shot, while the rest of us were expected to continue eating and making small talk.”

Holleran isn’t the only writer of the time to explore these ideas. In Close to the Knives, David Wojnarowicz’s memoir-cum-essay collection that explores the crisis with rage and humanity, also casts a light on the hypocrisy and falsehood that defined—and continues to define—so much political discourse. Wojnarowicz describes this as the “illusion of a one-tribe nation.” It comes from the idea that we are “born into a pre-invented existence within a tribal nation of zombies.” He’s right to describe nations as tribal, and to challenge the lie of solidarity that’s sold under the banner of the one-tribe nation. He goes on to say that “there are other tribes which work hand in hand with the government, offering slices of meat in the form of doubletalk; or hope—hope as a chain of submission.”

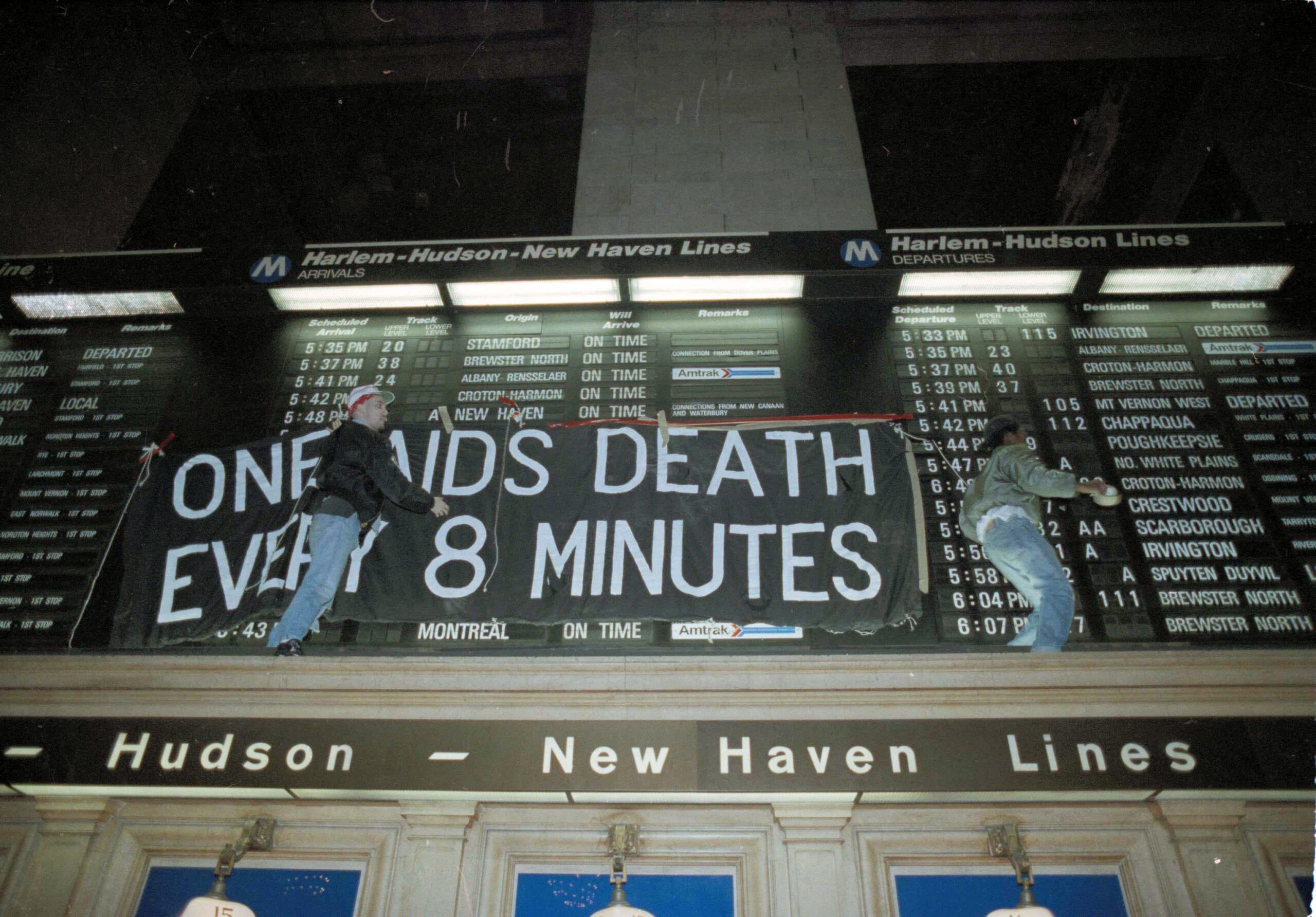

In a time when solidarity is being peddled by politicians around the world, this illusion is never more present. The language of solidarity is often hollow: Change doesn’t simply come from being told that we’re all in this together, but from activism. One thing that remains true in comparisons between COVID-19 and AIDS is that those who are most affected by the crises are the ones that fight the hardest to see things change, creating impact with deeds rather than words and refusing to accept the promise of hope and the incremental change that comes with it.

The relationship that AIDS writing and activism has with hope is another example of the stark rhetorical differences between the viruses. For some writers, hope was seen as the only thing that people had. As Holleran writes, “I suspect there is one thing and one thing only that everyone wants to read, and that is the headline CURE FOUND.” Hoping for a cure may have been the only option, but the reason for that hope came from a lack of solidarity, rather than an abundance of it.

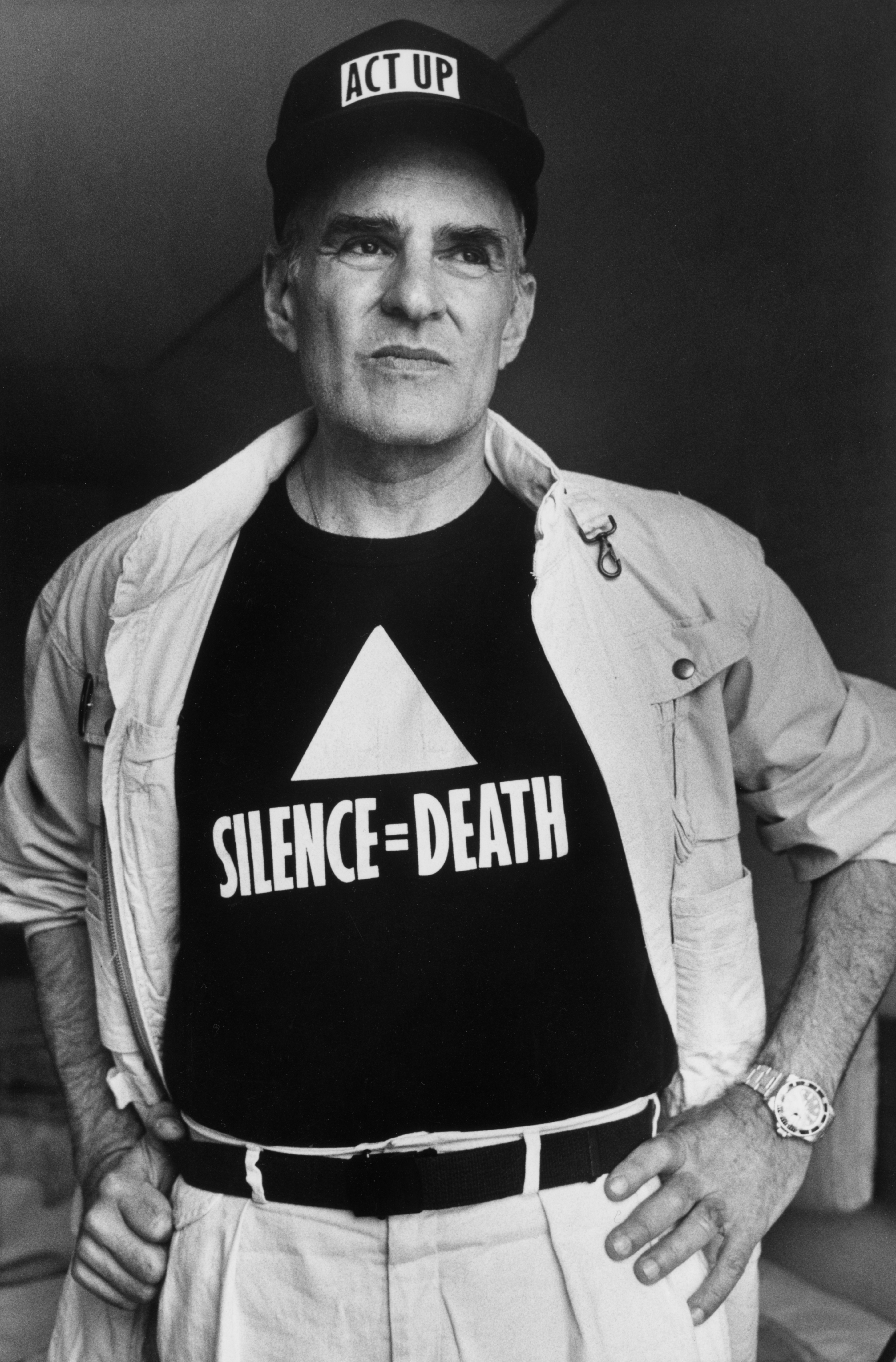

Larry Kramer poses for a photo in Montreal on June 5, 1989. Credit: The Canadian Press/Shaney Komulainen

Larry Kramer’s Reports From the Holocaust: The Making of an AIDS Activist is animated by this lack of solidarity and lack of action that he saw from governmental and medical institutions during the crisis. In one of his most famous essays, “1,112 and Counting,” Kramer asks, “Why isn’t every gay man in this city so scared shitless that he is screaming for action?” Kramer writes that “important, vital case histories are now being lost because of [the] cessation of CDC [Centres for Disease Control and Prevention] interviewing [of gay men with the virus].” He argues that much of this comes from the demographics who were most at risk during the AIDS crisis: gay men, people of colour and intravenous drug users. He writes about the lack of AIDS cases in straight, white people, saying, “I myself thought, when AIDS occurred in the first baby, that would be the breakthrough point. It was. For one day the media paid an enormous amount of attention. And that was it, kids.”

And when describing the lack of government money being put into AIDS research, Kramer argues that “there is no question that if this epidemic was happening to the straight, white, non-intravenous-drug-using middle class, […] that money would have been put into use almost two years ago, when the first alarming signs of this epidemic were noticed.”

“The most stark similarity between the two viruses is the ways in which they disproportionately affect marginalized people, particularly people of colour—all the while invoking language of solidarity to mask it”

This lack of information gathered from public health bodies is one of the most striking comparisons between AIDS and COVID-19. Each evening in the U.K.—and in most places across the globe—new statistics are released about the rate of infection, the number of people in hospital and the number of people who have lost their lives. Every night, politicians and scientists are questioned by journalists and members of the public about their approaches to containing the spread of the virus. To look at this in comparison to the situations that writers like Kramer and Wojnarowicz described and conclude that these situations are comparable is foolish at best and ignorant at worst.

In spite of the many ways in which the novel coronavirus and the AIDS crises are being compared, the most stark similarity between the two is the ways in which they disproportionately affect marginalized people, particularly people of colour—all the while invoking language of solidarity to mask it. Even a decade after the worst of the AIDS crisis, the tabloid news satire show, Brass Eye, was making jokes about the differences between “good and bad AIDS.” In Canada, the U.K. and the U.S. there’s still a waiting period of three months before men who have sex with men are able to donate blood—made all the more striking by the fact that in the U.S. the ban was only changed during the novel coronavirus outbreak. (The FDA fast-tracked changes on the restrictions around gay and bisexual men donating blood, turning it into a three-month wait.)

Wojnarowicz was right to call the period he lived and wrote in as being “strange and dangerous times.” The same is true of the present. But the response to that danger makes other kinds of comparisons ill-fitting. It’s a reminder not so much of what Holleran called “how far we’ve come, or at least how much we’ve assimilated,” but of the communal trauma that defined a generation of queer history, of the necessity for continued action and refusing to let small changes of language in the name of “solidarity” or “acceptance” act as definitions of progress. There’s still so much to learn and so much that needs to be remembered in our history.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra