It seems like a lot has happened in the world of HIV prevention in Canada since I began writing this column in March 2016.

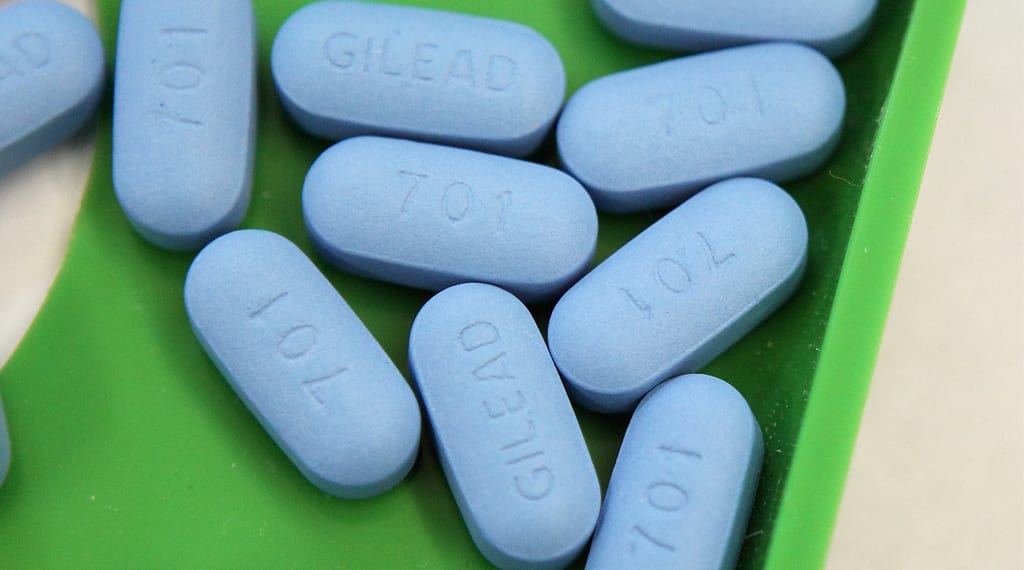

Pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, a medication that prevents the transmission of HIV, has gone from something that often felt sub rosa to now, where some people I know in my home province of Ontario are on it or at least understand it.

It seems like we’ve come so far. But I wonder whether we’ve really come far enough?

When Truvada as PrEP was first approved in the US by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012, I’d heard some rumblings about it but I didn’t really get what it was about until a couple of years later, when the AIDS Committee of Toronto (ACT) , launched a campaign to ask, “Is PrEP right for me?”

Whether it was right or not, many Canadians couldn’t afford it without a private insurance plan, seeing as it was going for over $900 a month. This kept it out of reach for those who needed it most. And since it had yet to be approved, those doctors who were willing to prescribe Truvada for use as PrEP had to prescribe it off label, since its intended purpose at that time was to treat, not prevent, HIV.

“There were known providers in certain pockets,” Chris Thomas, the communications lead at ACT, writes via email. “But generally it was not accessible.”

I was fortunate to gain early access to PrEP since my employer at the time covered most of the cost, and I remained on Truvada for as long as I was covered by that employer. At the time, I knew next to nobody in Ontario who was on it too, not like today.

Some people I talked to about it were curious but some were judgmental, reciting misinformation which was just a hodgepodge of rumours and fears.

Stories were also emerging of a generic version being ordered online from overseas via the US for a fraction of the cost. What was going for $900 a month was apparently down to $100, just by crossing the border to pick it up.

With a prescription, a US bank account and mailing address, and a way to travel across the border every three months, it seemed like a decent option — at least for those with disposable income and who lived a stone’s throw from the US.

I used a similar approach to access generics when I moved to the US and lost my coverage. I ordered the generic Tenvir-EM for a hot minute but it wasn’t a sustainable option for me.

Four years after the US approved it (and a month after I started writing this column), Health Canada approved Truvada for use as PrEP on Feb 28, 2016. Though it was a step forward, the approval didn’t really change access, nor did it affect cost. But at least it meant PrEP no longer needed to be prescribed off-label, legitimizing it amongst clinicians.

Earlier this year some generics were also approved in Canada. I naively thought that people would now be able to import directly to their home without having to cross the US border like some drug mule, but not quite.

Importation of pharmaceuticals is still prohibited by mail regardless of the drug, but it did reduce the cost of PrEP: as low as $250 per month but as high as $750. And $3,000 to $9,000 annually is still steep for many people when there are other tools like condoms out there, which do the job (perhaps not as effectively as PrEP but at a fraction of the cost).

It was starting to feel like we were being fed false hope, bit by bit, where things were being approved but access wasn’t changing — but then it did.

On Sept 28, 2017, PrEP finally became subsidized in Ontario via the province’s Trillium Drug Program, making Ontario the second province to cover it after Quebec.

PrEP activist and pharmacist Michael Fanous predicts this will finally lead to more men accessing PrEP.

“The number one reason why gay men don’t take PrEP is the cost: affordability of this medication,” he says. “With the cost coming down and having an increase in access to PrEP, we will definitely see a much higher rate of gay men willing to use PrEP.”

To be clear, this doesn’t mean that PrEP is now free in Ontario. It is, however, available at a significant reduction. For a single, low-income person earning $20,000 annually, they’d pay a deductible of $125 Canadian every three months, approximately $42 per month (costs can be calculated here.)

“That’s a barrier for folks still,” Thomas acknowledges. “It’s cheaper and it’s more affordable, but to say it’s fully accessible is a bit of a stretch.”

“That’s what our drug system looks like,” he says. “It’s almost never completely free.”

Quebec’s coverage isn’t totally free either. Under the Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ) there’s a maximum fee of $83.33 per month.

So it’s not perfect access, but PrEP is now significantly more accessible in two provinces. That just leaves the rest of the country. (And doctors across the country who may not know about PrEP yet or may be squeamish about prescribing it to gay men.)

Fanous also brings up another problem: some men aren’t aware that they’re at high risk of HIV transmission.

“I believe in the next two years we will see a lot more advancement in the community among gay men’s perception of being at elevated risk,” Fanous says. “And hopefully we will also see the same increase in the willingness to use PrEP because both of those are important predictors of uptake and adherence, which is incredibly important for the effectiveness of PrEP to the whole community.”

So the question remains — have we really come that far in the past 20 months since I started writing this column? Maybe, depending on which province you’re in (and even then there’s limits). Still, Thomas brings up a good point:

“I’d say, looking back, what’s been amazing is that people have been open to having conversations about something that they might not maybe feel comfortable about,” he says.

“We’ve seen a lot of people who were initially hesitant become champions for PrEP themselves, and starting to appreciate some of the benefits they didn’t immediately identify in their lives and then taking that forward in their group of friends, their online community,” he continues.

“So there’s an excitement around it that has slowly built.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra