Toronto Women’s College Hospital is celebrating its centennial this year and marks the occasion with a photography exhibition called Being She: The Culture of Women’s Health Through the Lens of Wholeness. Despite the many advances made in women’s medical care over the past century, inviting women to weigh in on healthcare is a courageously self-reflective way for any hospital to celebrate a landmark year. An open discussion about women’s healthcare means confronting the medical industry’s chilling complicity in denying women reproductive rights, moral panics around women’s sexuality and the great divide between those who offer care and those who receive it.

It is apt that the hospital should celebrate its century of service by calling on female artists to reflect on their own experiences with medicine and the medical industry, since we have long used various types of art and media to document our and other women’s experiences within the industry — often as tools of empowerment after distressing encounters.

Multidisciplinary artist Sarah Anne Johnson documents one such experience in striking detail.

In 2009 the AGO mounted a solo show of her House on Fire works, which centred on experiments carried out on her grandmother as part of a CIA-funded experiment in Montreal in the early 1960s. (Google MKULTRA to have your mind further blown). Photographs from that project are featured in Being She.

Her grandmother’s harrowing experience was carried out under the hallowed, nebulous and oh-so-familiar refrain of National Security. At the time it was the Cold War that was the mitigating panic, and what Johnson’s grandmother and thousands of other Canadian and American citizens endured at the hands of doctors and scientists, disregarding all tenets of moral and public law, is so sinister it defies belief. A bout of postpartum depression was all it took for Johnson’s grandmother to become an unwitting candidate for mind-control experiments that left her in ruins. Looking at research into these experiments, it’s clear that women who showed what would have been considered socially inappropriate behaviour or depression at that time were considered particularly suitable targets.

“The problem was there wasn’t any process,” says Johnson. “The doctors and nurses at the Allan Memorial thought that Dr Ewen Cameron [the director of the institute from 1957 to 1964] was a god. They never questioned him. He also had control of how and who got funding for research, so even if a doctor didn’t agree with his methods, they never spoke up, for fear of losing their research grants.”

Johnson didn’t hesitate when she was asked to present this troubling work in Being She.

“We have come a long way since then,” she says. “Doctors don’t have the same kind of power. Things have changed for the better because of people speaking out against the system, like my grandmother. They will continue to get better as long as people continue to stand up and use their voices.”

Victims and their family members have contacted Johnson to say that they are glad she is highlighting the events so people don’t forget.

“Digging up the family history is hard on me and my mother,” says Johnson. “She is very supportive, though, and thinks that my grandmother would be proud.”

Despite the strain, Johnson says she will continue to explore this history in her practice.

“Not all the time, though — it’s hard and I need breaks from it. I was very close to her. I was a kid [when she died], so we never discussed anything heavy, but I know that she felt deeply betrayed by Dr Cameron. And angry: angry at him, at the government and probably at herself as well. She was a fighter, and even though she had been terribly damaged, she forced herself to do the right thing. She hated her life being so public but forced herself to do it because it was for the greater good.”

Toronto-based Nina Levitt, the only artist commissioned to do a piece exclusively for the show, has created new photo works specifically related to the history of women at Women’s College.

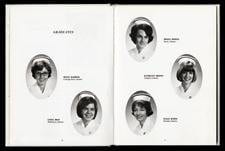

Levitt was given free reign to do anything related to the curatorial statement, so in keeping with her practice, she began her process at the Women’s College archive. Her work focuses on the nursing school yearbooks, with Levitt scanning open pages of all the books available from between 1959 and 1971, showing the shifts and changes in the profession of nursing.

In delving into these yearbooks, Levitt came upon something more profound than changing uniforms and hairstyles. As a collector of pulp fiction, she noticed deep similarities between the way nurses in pulp fiction at the time were represented and the way nurses self-represented, even within a more realistic framework.

Juxtaposing 15 blown-up images from the yearbooks against a collection of 100 pulp fiction novels from the ’50s and ’60s, Levitt found “striking correlations… There was a romancing of the profession in the novels that is in some ways echoed by the yearbooks. The highly stereotyped, institutionalized photographs do not reflect the profession.”

Levitt came to realize that what the yearbook photos represented most was an absence: an absence of the reality of nursing (as though it would have been unseemly and damaging to the glamorized image of the nurse to talk about the nitty gritty of the work) along with an absence of black women in nursing at the time.

“If you look at nursing today, it’s more multicultural,” says Levitt, who has commissioned writer and curator Andrea Fatona to write about the dearth of black women in nursing in Canada during the selected period. Levitt’s practice has always focused on what is unrepresented or unpublished and why, and exploring those omitted voices. As she says, “The archivists did find photos of black women in 1952 and 1958, years which were not documented officially, either because the students couldn’t find funds or they were not inspired to create yearbooks. We’re going to reproduce those along with Andrea’s essay, which documents the issues associated with black women’s education.”

Being She

Thurs, June 9–Mon, August 1

From June 9–15, the works of Jane Martin and Meryl McMaster are also featured, along with that of 20 local artists

Reception: Thurs, June 9, 7:30pm

The Gladstone Hotel, 1214 Queen St W

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra