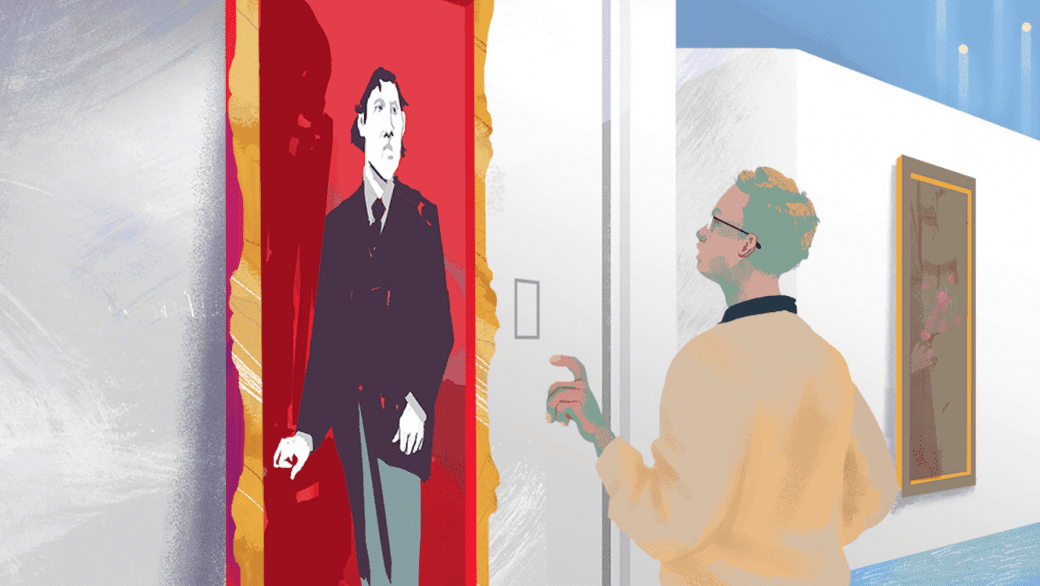

I wonder how many people can cite Oscar Wilde as one of their reasons for visiting Chicago. Maybe I’m the only one.

For Christmas 2015, my partner and I opted out of family dinners and other people’s timetables. We instead boarded a plane and spent a week in the Windy City, exploring the streets, checking out Boystown, eating deep dish pizza, taking a thousand pictures and walking far too much. We also practiced pronouncing our A’s the Chicagoan way, with a Y sound in front — hyappy, syandwich, cyalendar and so on.

And I kept my eyes peeled for Oscar Wilde’s tracks. He visited Chicago on his 1882 lecture tour of North America and, like any good fan or history nerd, I wanted to check out some of the places he visited — those that still exist, anyway. Most importantly, I wanted to make a pilgrimage to the Art Institute of Chicago, which is the intersection of a couple of what I consider to be Wilde-related historical gems.

It starts with Wilde’s visit to the institute. Well, he sort of visited. He did visit the Art Institute of Chicago, but in 1882 it was located in a different building and location entirely. And at the time its collection consisted primarily of plaster casts — not exactly the world-class museum it is today. It’s no wonder, as Roy Morris Jr writes in his book Declaring His Genius, an apparently unimpressed Wilde “wordlessly toured the Chicago Art Institute.”

It wasn’t until later that the institute was given the more impressive building it now inhabits at 111 South Michigan Ave — a building originally erected to wow crowds at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Before that, the site was home to the Inter-State Industrial Exposition Building, a sort of convention centre. And Wilde did see the Inter-State building, ghastly though it was, on his trip to the city.

The next factor is that the institute contains an actual Picture of Dorian Gray. American artist Ivan Albright created the painting for use in a 1945 film adaptation of a novel that Wilde wouldn’t write until several years after his North American tour. Known for painting mysterious and gruesome works, Albright was wonderfully well-suited to paint the picture that shows the effects of Dorian’s misdeeds while Dorian himself remains young and innocent-looking.

While the horror-drama is in black and white, as a special effect they (usually) shot the painting in colour to emphasize the transformation. By today’s standards this sounds like a bit of a joke and unworthy of the term “special effect,” but I recently watched a Blu-ray version of the film and can confirm that the effect is striking. Plus, it features a very young Angela Lansbury as Sibyl Vane, “a music-hall thrush victimized by Gray.” What’s not to like?

The final piece of the puzzle involves a later leg of the 11-month tour, when Wilde graced Canada with his presence for two weeks. In Ottawa he delivered a poorly-attended lecture. Then, after enduring being snubbed by the governor general the Marquis of Lorne (who, as someone rumoured to be gay, probably wanted to avoid being seen with Wilde), Wilde met with local artist Frances Richards, daughter of the lieutenant governor of British Columbia.

Five years after their initial meeting she painted Wilde’s portrait in London, where she had moved after studying art in Paris. During the sitting, he joked that it was unfortunate that he would age while his painted image would remain the same. “If only it was the other way,” he said. He later credited this remark as the inspiration for his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, which was serialized in 1890 and published in novel form in 1891.

With most of this swimming through my head, I was preoccupied as I wandered through the museum. My partner and I spent an afternoon there, me taking far too many notes and him usually off in other rooms after being driven away by my irritable muttering. Mentally, I alternated between reflecting on Wilde and trying to enjoy such great works as Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

(Photo credit: Jason Webster)

After over a century of bequests and expansions, the museum is labyrinthine. Eventually, somewhere beyond the Assassin’s Creed room (at least that’s how I like to think of the room full of ornate armour and all the halberds, spears and swords you’ve used to slice up your video game enemies in the guise of Ezio Auditore), we found Albright’s fantastic painting. It’s in the Modern American Art section, one room over from Grant Wood’s famous American Gothic.

Dorian stands next to a table that has a strange statue of a cat on it. Not only is Dorian no longer a handsome young man, the whole room seems to have been somehow corrupted. Even the wallpaper is peeling off in sections and the table is warped. Dorian’s scant, wiry grey-black hair stands on end. His crooked mouth is rimmed by boils or warts. His right hand is dripping blood and there’s a bloody knife on the table next to it. His crotch bulges strangely and his pants are stained yellow.

If I had to assign this Wilde confluence that fascinates me so much a more precise geographical location, it would be in front of this macabre painting. Wilde visited this institution and this general spot. Later in the tour he met someone — a Canadian — who would eventually inspire him to write The Picture of Dorian Gray. About 55 years later that book was made into a film and the painting commissioned for the film ended up back here, in this museum’s permanent collection. Right there in front of me.

To stand there and imagine myself in the middle of that kind of tangle of events and artifacts is this history nerd’s dream and the closest I’ve gotten to Wilde — yet.

(History Boys appears on Daily Xtra on the first and third Tuesday of every month. You can also follow them on Facebook)

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra