Considering what goes on in hotel rooms, there’s a certain playful logic to it. And yet New York it-boy artist Ryder Ripps’s latest project, Art Whore, caused a veritable shitstorm when it appeared earlier this month.

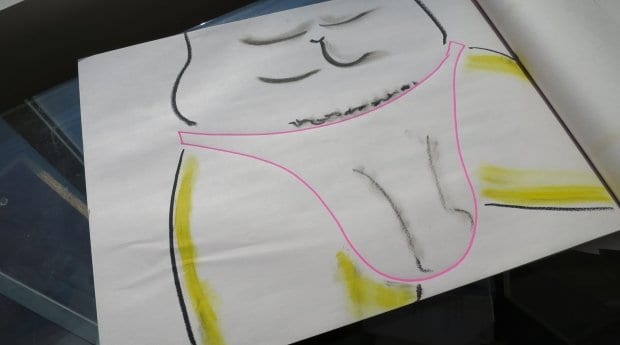

One of the participants in the Flatiron District’s posh Ace Hotel artist residency, Ripps was offered a free night’s accommodation and $50 to create a work. Taking his cue from the space, he turned to Craigslist, booked two sex workers and offered them $80 each to draw for him. His hired hands, “Brooke” and “Jay,” each hung out for about 45 minutes, chatting and sketching, then departed slightly richer.

Ripps understands how to get online attention. As head of the digital agency OKFocus, he’s shaped the web presence of such major brands as Nike, Diesel and Red Bull, as well as musician MIA. Not surprisingly, the project was documented in precise detail on his LiveJournal page, including the correspondence with his chosen artists, their original ads and the resulting work. But while he clearly wanted people to look, if his reactions in interviews following the debacle are to be believed, he truly wasn’t expecting the explosion of hate that ensued.

New York art critic Whitney Kimball said Art Whore was “in the running for the most offensive project of 2014.” Digital art organization Rhizome (which had recently shortlisted Ripps for the Prix Net Art prize) called it “unthinking, unethical, and dull,” distancing themselves from him. Ripps wrote about it on his Facebook page and received hundreds of comments, mainly attacking the work, before he deleted the thread.

“I did think people might morally object to the project,” Ripps tells me from his New York office. “That was my reason for documenting it so thoroughly. I thought if I showed there was consent and that we ended up having a mutually good time drawing in a hotel room, people would not be able to get on their moral high horse about the whole thing. I thought the hotel would have the biggest problem with it, but they were very reasonable about the whole thing, stating that artists should be free to do what they want.”

While the effect of the project is questionable, Ripps’s intention to point out the conditions artists are often expected to work under is worth discussing. In this case, a hotel “hired” an artist to work for them for an evening and offered nothing but a free room and $50 for supplies. A professional sex worker would be paid $1,000 to $2,500 for an overnight visit.

When juxtaposed with those who offer sexual services, the lack of value placed on the work of creative producers becomes clear.

And while I’ll admit that making the point by drawing a comparison between exploitation in the sex business and exploitation in the art world is iffy, the argument itself is valid. Writer Zing Tsjeng called the project “a white dude co-opting someone else’s labour in his struggle to make a point.” While he certainly made use of their artistic abilities, saying they were co-opted when they agreed to a set of terms and were paid the equivalent of $106 an hour to fulfil those terms doesn’t hold water for me. If artists averaged about $106 for the work they do, would we say they were being co-opted?

Among nearly every critique of the work, the term “exploitative” pops up. But in those jabs there’s a persistent underlying theme that selling sex inherently places those selling in a position of being exploited, something sex work activists continually dispute. As Ripps pointed out in our interview, “If I had called them interns, no one would have cared.” The point being that in the art world “intern” almost always means working countless unpaid hours, in exchange for being associated with a more successful artist.

In this case, two workers were hired to perform a service under agreed-upon terms, completed the deal and walked away with their money. There are legitimately people in the sex business who are exploited and abused. But the uproar over this project is misdirected. What gradually becomes clear in examining the responses to Art Whore is that it’s not so much the work that offends people; it’s the simple reminder that sex work exists and may even be happening in the room next to us.

Art Whore can be viewed on Ripps’s LiveJournal page.

Works are available by contacting ryderripps.com.

All proceeds from works sold will be returned to the artists.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra