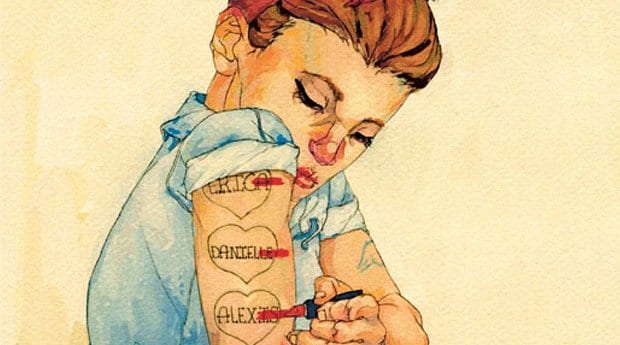

Hasbian Credit: Yigi Chang

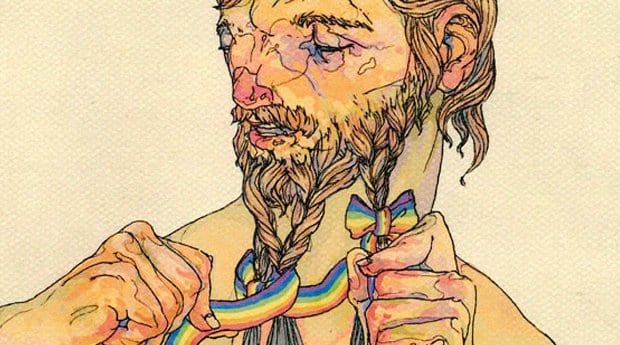

Beard Weaver Credit: Yigi Chang

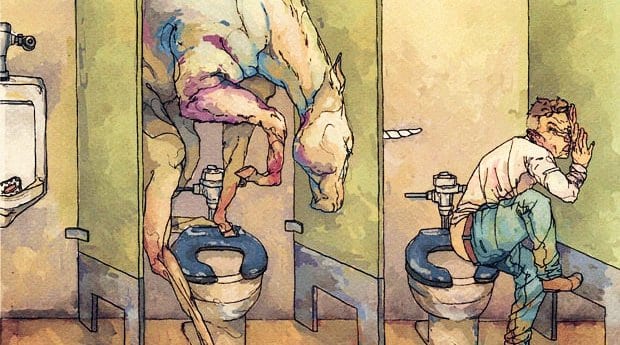

Glory Horn Credit: Yigi Chang

At first glance, one might describe artist Yigi Chang as “angelic.” His multicoloured tresses dance about his warm, friendly face. His default expression, a wide smile, is punctuated by eyes that sparkle with delight. But as soon as he opens his mouth to speak, the halo falls away and is replaced by red-plastic devil horns. This Markham-raised OCAD University graduate is a sex-obsessed sack of vulgarity. And he’s

deliciously proud to be.

Chang’s work splashes dicks, vaginas and buttholes in amusing patterns and situations across prints, tote bags, buttons and T-shirts. Not the first artist to focus on the nuts and bolts of queer sexuality, Chang’s unique addition to the genre is in his series of digital illustrations, which playfully account for the origin of community lexicon. It’s not the story that’s unique; it’s how it’s told.

Yigi Chang’s Queer as Folklore print series originated as his thesis project but is likely to continue as the years pass. After much visual (and experiential?) research, the artist settled on 10 ubiquitous queer terms, which he defined and then accompanied with whimsical illustrations. Each image is rendered using a digital paint treatment, alluding to watercolour, pen and ink and to the style of some best-loved storybooks.

The 10 prints — Beard Weaver, Closet Creature, Gold Star Gay, Rosebud, Hasbian, Fag Hag, Fierce, Glory Horn, Twincest and Self Sucker — evoke a fairytale-like mythology, weaving a playful narrative and history into otherwise commonplace, crude vernacular.

In Glory Horn, for example, Chang shows how a unicorn created the very first glory hole. “How did the first glory hole happen?” he asks. “No one knows. So I decided it was because a unicorn popped into a bathroom and drilled holes in the stalls with its horn.”

In Beard Weaver, Chang depicts a shirtless man braiding his long beard with a rainbow ribbon and shrunken heads. “Beard is about putting on a show for society, lying and deceiving someone else to hide your true self,” he says. “You literally adorn yourself with other people, regardless of how it affects them.”

Hasbian features a pin-up-style woman using lipstick to remove the feminine suffixes from names tattooed on her arm — turning Erica to Eric, Danielle to Daniel, et cetera. There’s a touching sadness in this image, despite the residual humour in the series’ concept, which spills over from print to print.

Chang manages to work with stereotypes rather than simply reinforce them by cleverly combining exaggerated scenarios with absurdity and a modicum of pathos. What good is a fairy’s tale without an allusion to morality?

Some of Chang’s other illustrations, though unconnected to Queer as Folklore, don’t stray far from the themes of sexuality, mythology or double entendre. His Solvestra print shows a visual recipe for a cure-all tablet. Ingredients: fairy dust, unicorn horn and strands of hair from Santa Claus’s beard. His oil-on-canvas paintings from another series look like censored screen-shots from adult movies applied with broad, colourful brushstrokes.

Chang’s artistic voice is influenced, at least in part, by an obsession he had with internet porn growing up. He marvelled in the salacious, forbidden delights of naughty photos and videos — the subject matter notwithstanding — even devising clever ploys to sneak peeks when he was in the same room with his family.

“I used to watch porn with multiple browser tabs open, so I could switch it to something else if my mom walked by,” he says. “I would pretend I was listening to Britney’s ‘Stronger’ so no one would suspect. It got to the point where I would close my eyes and see flashes of pornography all the time.”

Despite the subject matter of his work, Chang’s mother is a staunch supporter, staffing his table at craft fairs and boasting (perhaps with a tinge of relief) that her son is completely self-taught.

“Mom’s hilarious. She’s so supportive, always bragging to people about how I learned on my own, ‘without a cent toward art classes!’” And without much mention of the subject matter. “She doesn’t really address the content of my work. She just praises how ‘original’ it is.”

Underneath the candid triple-X thematics of Chang’s work there is a genuine love for the queer community and an underpinning of activism. “Personally, I don’t dislike the association between ‘gay’ and ‘sex.’ That’s part of the main differences between homo and hetero: the ‘sexual’ part,” he explains. “I want to go right to the moment of attraction, stay there and make sure people aren’t questioning it. Make them okay with the idea, comfortable even.”

Look for Chang’s table at WorldPride this year on Church Street. He’ll be sharing some new designs (possibly including a pentagram/penis design involving glow-in-the-dark ink as ejaculate), buttons, tote bags, temporary tattoos and more. Or, if you can’t wait until summer, visit him at yigichang.com or find him on Etsy (etsy.com/shop/yigichang).

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra