Is it too easy or too obvious to say that we live in a memoir-saturated era that shows no sign of letting up? Is it time to accept that fact and simply let go of what must surely be considered an antiquated notion – that writing the story of one’s life is not the privilege awarded after say five or six decades of life? These are, after all, accelerated times, and two or three decades of life provide vast amounts of material, not to mention adequate time to reflect on that material. It is easy to argue that we all have something to say and who’s to say when it’s appropriate to say it.

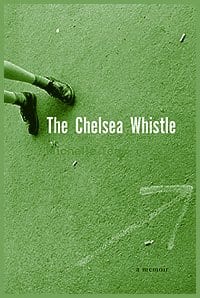

It’s hard not to think along these lines when reading Michelle Tea’s The Chelsea Whistle, a memoir of growing up in Chelsea “a town five minutes from Boston that might as well have been five hours, five days.” And yet as the book demonstrates there are advantages in writing while the memory is still fresh and painfully vivid. And Tea is fascinated by her own precocity and has been for most of her life.

An early interest in the musical Annie sparks her ambition: “All I wanted was to be an orphan. I knew I could do it, I could be one of those girls. It wasn’t fair. It was just like the year before, when I read in a kid’s magazine about the youngest girl ever to write a book. She was five years old. I gasped and moaned. I myself had been planning on being the youngest girl ever to write a book, but I was already seven and had no connections, and some five-year-old jerk with a mom in the publishing industry beat me to it. Time was slipping away, I would never be the youngest kid to do anything, I was too old already.”

Growing up in a lousy town, going to Catholic school, taking dance lessons, getting into fights with girls and boys, listening to your parents fight, being obsessed with toughness in others and cultivating it in yourself, and constantly fantasizing about escape in one way or another are just part of Tea’s everyday childhood life. Obviously, this is bleak stuff and yet there are dozens of childhood memoirs that cover the same kind of ground. But the strength of the book is in the way she presents it. Tea is a good writer and she knows how to tell a story. She can take an ordinary event, whether it is a family dinner or a walk to the grocery store, and turn it into a fully realized, nearly cinematic event. Each chapter could be an episode of what we would now call reality TV.

There is a value in the recollection of minutiae of childhood and the overall effect of the book is to remind us of that value. The strange thing is the way that at times the book reads more like fiction than autobiography. This could be because the subject matter (growing up unhappy) is most often done in the form of a novel. The fact that we are allegedly being told a true story, a “this is what really happened to this person” story, rather than a fictionalized “this is what really happened to me but I’m framing it as novel” kind of story is disconcerting but interesting. Many parts of it read like a novel.

The weakness of the book is that it is much too long. Three hundred pages is a lot of memoir. And after a point, one adolescent misadventure is pretty much like another. The seemingly exhaustive cataloguing of misadventures truly captures the flavour of adolescent life if only because it serves to remind us that profound boredom is really the dominant feature of adolescence. But it doesn’t need to be replicated page after page; it’s not that difficult to apprehend.

Which brings me back to the larger question about nature of autobiographical writing: Is it necessary? The question becomes what’s new about this specific endeavour and here the answer is that Tea doesn’t break any new ground in terms of growing poor or growing up with a vision of something better, and in terms of revelation of details about her particularly unpleasant family life, again there’s nothing new. That she tells her story with minimum of sentimentality and a genuine ability to write is huge advantage without which The Chelsea Whistle would be completely ordinary.

Everyone is entitled to their acts of narrative therapy, but is it art?

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra