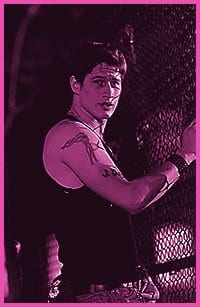

John Palmer’s new feature Sugar ended up being something quite unexpected – it’s not a rehashing of well-worn themes of sex and drugs. Sugar succeeds because it challenges its audience to connect with its material without holding us by the hand and explaining how we should be feeling. Over the course of this trim digital video feature, we see Cliff (Andre Noble), who has just turned 18, seek adventure outside his suburban home, meeting a young hustler named Butch (Brendan Fehr) who becomes his “buddy.”

The film is originally based on stories from Bruce LaBruce’s influential 1980s Toronto queer punk zine JD’s, mediated through cowriter and associate producer Todd Klinck’s own experiences as a prostitute. According to Klinck, the project transformed from what was originally a period film to an updating of LaBruce’s stories (keeping them in Toronto) – with LaBruce’s blessings and sensibility guiding the project. The film is a stew, 12 years in the making, of real-life experiences and of fiction from the minds of several queer co-conspirators.

Sugar wears its zine roots on its sleeve with its cut-and-paste opening credit sequence and its casual disregard for linear narrative. “I didn’t want narrative,” Klinck states bluntly, “I didn’t want plot. I didn’t want structure. I didn’t want any of that.” The film focusses on the complicated ways that its many characters try to interact with each other, whether for pay or not. It is not about introspection and growth. The story is kept intentionally sketchy. Many characters appear for one scene and then disappear. “I like random characters,” says Klinck. “You just get them for a minute, you get their essence and then bye-bye.”

Sugar captures that familiar phenomenon of meeting someone once or twice and never seeing them again, leaving you either to wonder what ever happened to them or to forget them entirely. What makes this tactic successful is the feverish, dreamlike quality of the film that brings to life the fragmented vignettes and messy memories represented. Palmer says he trusts that audiences are, “used to life being inexplicable and crazy.”

This aspect of the film may not suit everyone, as it can be difficult to watch a major character be treated with sincerity and affection throughout the film only to be flippantly dispatched with at the end. It does fit with the film’s determination to never give the audience easy emotional release, so in that sense it is more like frenzied reportage animated by LaBruce’s signature glibness. “Bruce refuses to take anything seriously in the stories,” says Palmer.

Other than Cliff and Butch, the two most prominent characters are Cliff’s world-weary young mother and his little sister Cookie who is brilliantly brought to life by Haylee Wanstall. She is a sassy preteen fag hag who is wise way beyond her years. A memorable scene has her smoking with Butch; they barely speak but still share a moment of deep intimacy. Like many scenes, you do not immediately know whether it will be played for drama, sleaze, humour, quirkiness or tenderness – the emotional tone of the film is quite uneven, even chaotic. It works because this harsh quality is the film’s means of frankly portraying often random events without regard for our desires for the closure and meaning that real life often does not provide. From the broad, over-the-top comedy of a toilet stall merchandise inspection or masochistic Stanley’s erotic dish-breaking to the subtly moving scenes of Cliff and Butch’s awkward first night in bed and Cliff’s birthday party with his sweet family, the film’s range is quite remarkable.

The filmmakers made a concerted effort to present an insider’s perspective of the hustling scene. Klinck says he was obsessed with countering stereotypes about sex work. “I didn’t want this to be another hustler movie,” he says. “I didn’t want it to be a direct ‘clients are awful’ thing. It’s not as simple as that.” Unlike the majority of films about sex work, Sugar doesn’t demonize the clients. At one point Butch explains to Cliff that sometimes you are required to be a character and sometimes a technician. In another scene Cliff enthusiastically proclaims Butch’s date with an obese woman an “act of compassion” but Butch is more inclined to see it as just $300. Sugar captures the complexity of the relationships between workers and clients by not making generalizing statements about the trade, instead using the insight that comes from personal experience. As Palmer puts it, “There’s no judgment.” Nothing has to be sugar-coated or explained to us.

The filmmakers also never underestimate the intelligence of their young characters. “[Cliff] knows everything because he grew up in the Internet era,” says Klinck. “He knows everything there is to know about every type of sex, every type of gender, everything – he’s read about it and seen it but he’s never done it.” According to Palmer, this respect for youth can be traced to LaBruce. “[LaBruce] wrote those stories for 14- and 15-year-old gay kids, telling them that sex was okay… a revolutionary idea.”

Palmer and Klinck confirm suspicions that accessing funding was difficult. “People were afraid of the material,” says Palmer. “[Sugar is] slick, it looks like a Hollywood movie… I wanted it much more verité… and [more] hard-ons.” While it may not be as “rough and raw and objectionable” as the filmmakers would have liked, Sugar’s success at the 2004 Inside Out festival (winning the best feature award) suggests that it still hits a nerve.

* Sugar opens Fri, Jun 25 at the Carlton (20 Carlton St).

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra