Thank you, John Hughes, for changing the way we think about high school.

As the director of Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club and producer of Pretty in Pink (among others), he changed the channel: away from endless “What am I going to do after high school?” films, and toward films that explored the psychological stresses of high school in itself. In particular, he showed the tensions between the two dominant teen poses — “I want to belong” and “I want to be myself” — and in so doing, forced a generation of filmmakers and two generations of audiences to contemplate conformity and social expectation as it applied to teens.

Needless to say, it’s a theme that resonates with gay and trans folks, who are plunked into high schools where the rules (often unspoken, often set by other students’ behavior) don’t make sense to them. Hughes ushered in a whole generation of films about high school that took queerness (in its ordinary meaning) as its subject. Being an outcast and feeling different became the central subject of teen comedy for almost a decade — and it is for that reason that queers have re-watched the brat pack films ceaselessly for almost 30 years.

We don’t appear in the films of John Hughes, although if they had been made 15 years later, we probably would have. Since Hughes, we’ve shown up in all kinds of teen flicks: as the drug-dealing Joshua Jackson in Cruel Intentions, as the gay cheerleader in Bring It On, as Jena Malone’s boyfriend in Saved, plus characters in Heathers, Wild Things and Pump Up The Volume. We’re placed in these films because queer characters are often free to express themselves in ways that contrast the high normalcy enforced by (and on) the other characters.

I’m getting ahead of myself a little.

Those films — from Pump Up The Volume to Saved — would look very different without Hughes, who redefined the essential struggle of the American teenager.

***

Let’s set the stage. Immediately before Sixteen Candles, there was Flashdance (1983), All The Right Moves (1983) and especially Footloose (1984). These are movies about the place of young people in the world. In Flashdance and All The Right Moves, the looming threat of the factory provides the dramatic tension. The fear is that industrial life will consume the characters unless they can find a way out. Kevin Bacon in Footloose fights an almost epic battle against the big three intergenerational villians: family, the church and the law.

Returning to those films, it’s now easy to see a missing element, a gap tooth in the emotional life of the young protagonists.

What is missing is the complex, internecine social universe that is the modern high school. The conflicts in these pre-Hughes high school movies — and earlier genre films like Saturday Night Fever — were external to young people. The biggest problems for teenagers were bad bosses, the high cost of college and the possibility of failure in the so-called real world.

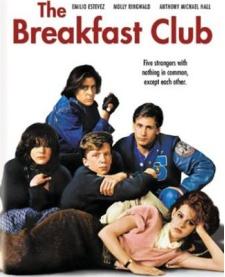

Then, in 1985, came The Breakfast Club. Reality check.

It’s the world inside high school, not the world outside it, that makes being a teenager so hellish. Young people find themselves caught in a world of complex hierarchies, rules, behavioral expectations, and lacking a language for talking about it, they see little hope of navigating the tempestuous waters.

The conversations — monologues, really — at the heart of The Breakfast Club are the beginning of an articulation of that experience. It pushes the world outside of high school out of the frames, both literally and figuratively. Parents are barely a blur. All teachers are absent (replaced by the principal and a janitor). As they talk, they reveal why it’s hard to be a high school student. Cliques. Expectations. Zits.

It is essentially a critique of the status quo, framed somewhere between a primal howl and The Graduate. Claire’s naïve assertions in the film’s opening minutes are explored and challenged by each of the other young characters over the course of the film. Sure, it is cartoonish, but it is also archetypal, with each of the five students putting forward a different philosophical lens for high school (Platonic, Machiavellian, cynical, romantic and Hobbesian). It wasn’t the final word, but it was the beginning of a dialogue that didn’t exist before the film.

Yet Hughes looked into the dark heart of American high schools and found a profound truth. Often the greatest source of teen torment isn’t inflicted from parent to child or from teacher to student, boss to young employee — torment is often passed from teenager to teenager. Adults need not be involved.

In Sixteen Candles (1984), the film Hughes shot immediately before The Breakfast Club, we see the social codes depicted without all the verbiage. We like to think of the plot as pretty straightforward: Sam (Molly Ringwald) is in love with Jake. Jake is a popular, older kid. Almost inexplicably, Jake is also jonesing for Sam and in the closing frames, they get together. Hot.

The film is a fantasia, the ending a spoon of sugar that helps the medicine go down. But scratch the surface, and the film is abuzz with the kind of social drama that is only talked about in The Breakfast Club. The geek is mostly concerned with his social status. Jake’s girlfriend uses markers of upward mobility to keep her friends subordinate. There’s a money and class distinction (played out by comparing vehicles). And all of it is watched, in bafflement, by the foreign exchange student. High school is a whole different culture, Hughes seems to be saying, as different to adults as the US is to Long Dong.

***

Like all art worth remembering, The Breakfast Club sparked conversations that continued after Hughes’ retirement. Having whetted our appetites for stories about teen-on-teen meanness, Hollywood produced a string of low-budget comedies about the high school experience.

Fast Times at Ridgmont High, Heathers and Pump Up The Volume picked up the torch and ran with it. Heathers, possibly the best of the lot, uses The Breakfast Club’s model of social hierarchy and cliques as its starting point. Without Hughes, the film would be indecipherable.

But it could not last forever. By the mid-90s, critiques of high school norms were replaced by facsimiles of critiques. Realizing that teen films are inexpensive to make but often profitable, studios greenlighted a slew of titles about high school that dealt with the same subject as The Breakfast Club and Sixteen Candles, but didn’t have anything to say — vapid films like She’s All That, Ten Things I Hate About You, Never Been Kissed and the worst of the lot, Can’t Hardly Wait.

It’s a tribute to Hughes that high-quality films on this subject are still getting made, however infrequently, courtesy of folks like director Brian Dannelly (Saved) and writer Diablo Cody (Juno).

Of course, it’s not just gay people, but all outsiders that find affinity with the genre. With the brat pack, we learned something we can never unlearn. And so, for the final time, we thank you, John Hughes.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra