Terry Galloway, self- described “mean little deaf queer,” began her gauntlet of endurance while still in the womb in post-war Germany, where her dad worked at a US Army base. Her mother Edna was given a near-fatal dose of mycin antibiotic to treat a kidney infection. Mum survived, enabling first-born Terry to spend her early years in the strange world of rubble-strewn Stutt-gart and its streets filled with unwashed and demoralized Germans, a surly bunch of whom had once tried to push pregnant Edna out the door of a city bus. Quoting from her mother’s anecdotal storehouse (the family were devoted kitchen-table raconteurs), Galloway offers the striking image of an ex-Nazi soldier assigned to stoke the coal-fired furnace in their requisitioned house, “his face all red from the heat… feeding the fires… knowing what his people had done.”

Speaking for herself and more severely disabled friends, Galloway draws an unbroken line between malevolent Nazis and people whose response to a disabled child is to “gawk like you’re some kind of nasty insect.” Still, Galloway makes a point of recording her sensual childhood affection for her German nanny. “I used to press my nose against [her] and breathe her in deep. I loved the aromas ingrained there of fried onions, peeled oranges and her own delicious sweat.”

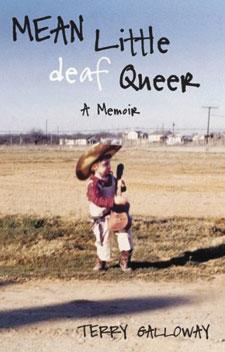

Her fetal encounter with mycin had long-term ripple effects. At age nine, by then residing on a sun-scorched Texas army base, she was wondering why “the voices of everyone I loved had all but disappeared.” At kitchen gabfests she was secretly learning how to read lips, afraid to breathe a word about her shrinking aural world. Her vision was also getting blurry. Standard hearing and eye tests at school led to corrective devices: thick “Coke-bottle” glasses and clunky plastic hearing aids that screamed “freak” to all around her. Her solution was a “sacred quest” to become a boy — which she managed with brutal aplomb, joining a school gang that targeted pubescent femmes, pinning them to the ground and force-feeding them gobs of spit. The power trip wore off when she began to see herself in her victims’ pleading eyes.

At the local “Camp for Crippled Children” she confronted her impulse to recoil from kids with limbless and spastic bodies that “might as well have popped up from some Grimm brothers’ underworld.” At school she avoided bullies by “cultivating a talent for risk and self-mockery” inspired by some of her fave comedians: Lucille Ball, Carol Burnett, even Daffy Duck.

At 13 she looked up “homosexuality” in the dictionary then casually mentioned the term at a family meal. “I didn’t have time to finish the word. It was like I’d shot off a gun and stampeded the cattle.” The uproar didn’t deflect her queer hormones from their course. She developed a serious crush on her high-school debates teacher, whose hands-on methods of teaching pronunciation and breath control suggested a thinly veiled desire. “It’s no wonder I longed for her, that my longing blossomed into an ache I feared, exulted in, and kept in check…. The same way I tried to keep my feelings for boys in check. I liked exploring their bodies, liked the rank smell of them when they’d get excited.” It seemed any glimpse of penis or breast was equally thrilling to her.

By 19 she was in American Studies at the University of Texas, hopping in and out of bed with a smorgasbord of guys and gals while wracked by cycles of binge-and-purge, “a never-ending love/hate relationship with my body.” Still living with her parents, she set up her bedroom closet as a private retreat with a big bowl to catch the upchuck from her compulsive intake of ice cream and cookies. “I was sure the lesbianism… like the bulimia, was a passing thing.”

Out of the blue, she fell for a French woman at a poetry reading: Isabelle. Their first tumble in the sheets spurred Isabelle to dump her girlfriend the same night, launching a three-year relationship that triggered Galloway’s coming out moment to her parents, who’d already taken a shine to Terry’s new friend. The smitten lovers got hugs and a declaration: “Isabelle, we love you.”

By the 1990s Galloway was in theatre studies at Columbia, leading to work with Manhattan’s edgy theatre collective, PS 122. Her identity still precarious, she at one point spent six weeks in a psych ward — fuelling one of the better comic turns in the book. Back in Texas for a visit, she met a graduate student named Donna Marie. “Time stood still.” Donna Marie became the long-term keeper: “my truest of true loves.”

Though the haphazard chronology of this memoir often makes for confusion, Galloway’s wry humour and unflinching candour carry the book through to its apt conclusion. Looking back from age 57, she allows, “Mine was a happy life, when I could stand it.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra