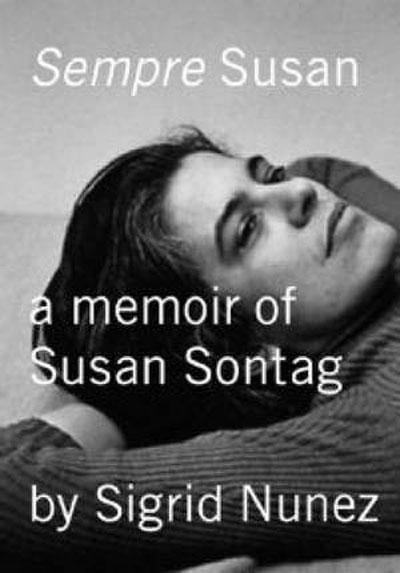

In the early pages of her revelatory new book, Sempre Susan: A Memoir of Susan Sontag, critically lauded novelist Sigrid Nunez invokes Nabokov’s maxim: “Caress the detail, the divine detail.” It is through the caress of Nunez’s details that, perhaps for the first time, a portrait of Sontag as a fully rounded human being emerges from the mire of beatification, deification and vilification that continues to surround her, even seven years after her death from cancer in December of 2004.

Nunez met Sontag in the spring of 1976. A colleague at the New York Review of Books recommended the recent Columbia grad student as a personal assistant for Sontag. Nunez would eventually move into the Upper West Side apartment that Sontag shared with her son, the writer and editor David Rieff. Sontag became Nunez’s mentor and Rieff her lover.

Nunez paints a nuanced portrait of Sontag in all of her contradictory glory. In one moment, Sontag is the star of a thousand literary soirées, entertaining cultural elites and infecting young writers with her boundless enthusiasm for beauty, art, the life of the city and the life of the mind. In the next, she is a lonely figure desperate to remain constantly occupied lest she succumb to the terrifying white noise of the emptied mind.

Nunez has a flair for the epigram and her anecdotes deftly skip from pathos to bathos, even eliciting the occasional belly laugh (rarely have parentheses been used to greater comic effect). Through Nunez’s recollections we see shades of Sontag’s legendary imperiousness and the full force of her unapologetic cultural elitism, but Nunez also reveals in Sontag a fragile earnestness that invariably lurks beneath the surface of the hardhearted. Nunez acquaints us with Sontag the mentor, Sontag the mother, Sontag the genius, Sontag the nightmare, Sontag the friend.

Xtra: I think it would be fair to say that public opinion about Susan Sontag encompasses a very wide spectrum. In light of the fact that one often finds such strong feelings about her in so many different social and artistic spheres, what — to your mind — is her legacy? Do you think she should be best remembered as an intellectual, an author or an activist?

Nunez: I think, most accurately, she should be remembered as all three, though as a writer above all. I think she herself would have wanted to be remembered as someone who left behind a worthy body of work and who also tried to be a force for good in the world.

Xtra: What do you think is the most lasting lesson you took from Sontag’s mentorship?

Nunez: That everything mattered, as she put it. That it was essential to be serious and passionate and to be curious about everything. That wanting to be a writer was a grand and noble ambition, and that there was nothing wrong with a woman for whom work was more important than marriage or children.

Xtra: Did Sontag ever discuss her personal feelings toward her bisexuality? What was her private relationship (if any) to queer rights?

Nunez: No, she didn’t discuss her bisexuality. She expected it to be accepted; it was who she was. She was all for queer rights, as she was all for other civil rights.

Xtra: Is there a particular impression of Sontag that you hope your readers take away from the memoir, and was it partly your goal to try and correct some of the established views about her?

Nunez: I just wanted to describe the Susan Sontag that I knew, as accurately and as vividly as possible, and to reflect on what knowing her has turned out to mean to me. And that seems to be how most people have been reading the book. However, I’m dismayed by the one or two who have seen in Sempre Susan an act of revenge. Anyone with a little imagination can figure out what this memoir would have been like had I really been out for revenge. And there are some who’ve seen the book as an act of worship. Also wrong. I greatly admired Sontag, but I did not worship her. I don’t worship any human being. I worship cats.

* * *

As Edmund White, who recalled his tumultuous friendship with Sontag in his recent memoir, City Boy, wrote in the Guardian after her death, “she was irreplaceable and she won’t be replaced.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra