“Didn’t we have the question wrong in the first place? Why shouldn’t we expect politicians to be open about their sexual orientation? After all, if they are asking for our trust, don’t we need to first trust that they are telling us the truth about themselves?”

In today’s Globe and Mail, a longtime friend of Keith Norton wrote about the impact of having an out gay Tory role model. Norton, a former provincial cabinet minister, died Jan 31 at the age of 69. The short version of the account, written by Randall Pearce, leaves out some of the more pointed parts of the commentary. Here we reproduce Pearce’s essay in full.

Norton brought sexuality out of the electoral closet

By Randall Pearce

Should we expect political candidates to be open about their sexual orientation before Election Day? Ask any young voter and you’re likely to hear, “Well, only if they want my vote.” While living a double life might be a political liability today, it was the accepted route to success at the ballot box until fairly recently. This week we farewell Keith Norton, a former Ontario cabinet minister and human rights commissioner, who was among the first to turn that perverse orthodoxy on its head and bring sexuality out of the electoral closet, just twenty years ago.

The provincial election of 1990 was a watershed year for gay politics in Toronto’s St. George-St. David riding (now known as Toronto Centre provincially and federally). Keith Norton, a veteran cabinet minister of the Davis era, announced that he was running as part of the first Mike Harris team and, in so doing, came out of the closet. While Norton wasn’t the riding’s first openly-gay candidate (Doug Wilson ran openly for the NDP in the federal election of 1988), his campaign made waves because it was so unexpected.

Norton was not a first-time NDP candidate like Wilson, he was someone who had been ‘minister of everything’, having spent seven years in cabinet (out of ten in the Legislature) in senior portfolios like community and social services, health, environment and education. Some accused Keith of using his coming out to lure gay voters in a cynical attempt to stage an electoral comeback (he had lost his former seat of Kingston-and-the-Islands in the 1985 election that saw David Peterson’s Liberals take government from the Tories). However, nothing could be further from the truth. Here are three good reasons.

One, there were few votes in being openly-gay in 1990 and even fewer for Tory politicians. The gay voters that Norton’s opponents accused him of manipulating were anything but welcoming; many felt he should have come out when he was a member of the provincial cabinet, not when he was trying to get back in. As a young campaign worker canvassing the apartments of the Church-Wellesley neighbourhood, I heard the anger first-hand.

Two, Keith’s coming out may have taken a bit of the shine off his candidacy in the eyes of some of the more conservative Tories, north of Bloor. They might have thought that they were getting a true blue cabinet minister as befitting Ontario’s richest neighbourhood when what they got was a social and political reformer more akin to their southerly neighbours in Ontario’s gayest neighbourhood. Almost certainly, his announcement did nothing to swell the ranks of PC campaign workers needed to canvass the towers of St. Jamestown and ‘the Village.’ That job was left to newcomers like me and former Kingston-and-the-Islands campaign workers who had relocated to the city.

Three, Keith was unable to capture the lesbian and gay vote because his opponent was also gay – the closeted Liberal Attorney-General, Ian Scott. At the time, not all gay voters preferred their politicians ‘out’. Many discretely supported Scott over Norton. However, it became increasingly uncomfortable for Scott and his supporters as the campaign played out and ‘the question’ was brought into the open at more than one all candidates’ meeting.

For Keith Norton, coming out in the 1990 election wasn’t cynical, it was cathartic. Keith was a man completely comfortable in his skin. I recall him telling a bunch of us one night how he had been out to his family since he was a young adolescent (which must have been some time in the 1950s). Keith never made any pretence to be anything other than who he was. He didn’t have a same sex life partner but he wasn’t married either.

By 1990, it was uncomfortable for any of us to remain in the closet while we were burying our friends. Death was the ultimate ‘coming out’ for so many and it was easy to feel guilty for just being alive. Although Keith was not out while he was in cabinet, he did work behind the scenes for the welfare of gay men. I recall vividly how he described the first years of the AIDS epidemic when he held the health portfolio (1983-85). I know that he did all he could at the time although there was precious little that could be done. My impression was that coming out for Keith was a way of squaring his public profile with his private political behaviour, not the other way around.

The impact that Keith’s coming out had on young, gay Tories like me was powerful and life changing. With someone like Keith leading from the front, it was all of a sudden possible to be openly gay in the backrooms. Not only did we knock on the doors of Church and Wellesley but we entered the salons of the Rosedale matrons without apology or pretence. Because Keith Norton came out, I never had to be in the closet, politically speaking.

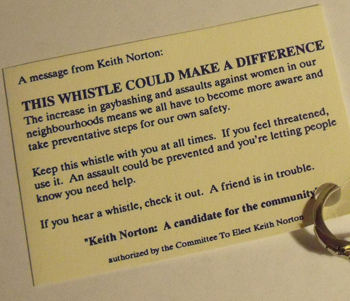

While we might have been powerless in the face of AIDS at that time, we were still able to fight violence in the streets. Gay bashing was a serious issue in 1990. We fought back with simple, chrome-plated whistles. Somebody found enough money to purchase a thousand of them for the campaign. They carried a simple message on a printed card:

No party logo; no partisan spin. In our hands, these whistles were weapons of truth. Night after night, we would hit the bars on Church Street and press the whistles into the hands of patrons, never saying a word. We didn’t have to. Word about them spread further and faster than we could have hoped for. Ian Scott’s campaign manager, a gay man himself, was red-faced with embarrassment when our paths crossed at Woody’s.

The outcome of the 1990 election in St. George-St. David was a seemingly insignificant footnote to the main story – Bob Rae’s NDP had managed an upset victory over the Liberals, winning government for the first time. The incumbent, Ian Scott, was re-elected, albeit as a backbencher. Keith placed third.

For us, election night was a tearful affair. However, through our tears I think we realised even then that politics would never be the same in downtown Toronto. It would take more than ten years to rid the riding of sexually ambiguous candidates and their compromised supporters but we made a start that night. We made gains for truth in politics that will never be lost. Whatever the party, anyone today who stands for public office as an out gay candidate in Toronto Centre will be standing on the shoulders of a giant.

Didn’t we have the question wrong in the first place? Why shouldn’t we expect politicians to be open about their sexual orientation? After all, if they are asking for our trust, don’t we need to first trust that they are telling us the truth about themselves? If young voters take that for granted when they go to the polls this year, Keith’s work will be done.

Randall Pearce was the last federal Progressive Conservative candidate in Toronto Centre-Rosedale. He fought the 2000 general election as an openly-gay candidate. He lives with his husband in Sydney, Australia.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra