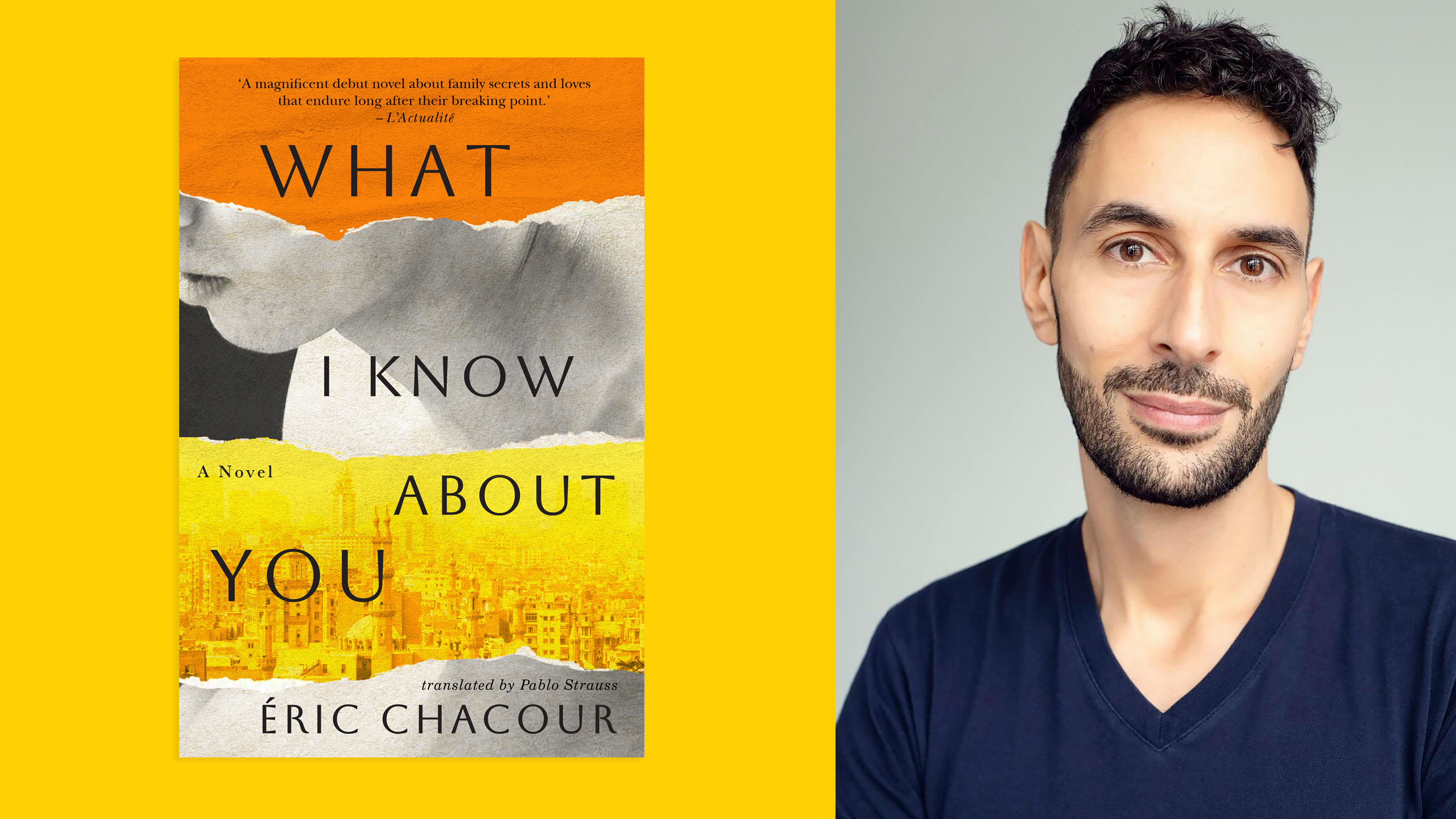

Éric Chacour’s first novel, What I Know About You, enters the stage of English-language literature with a dizzying number of French-language prizes and nominations already attached to it: Ce que je sais de toi, the original French-language version of the text, won the French Booksellers’ Prize 2024, the Prix Fémina des Lycéens 2023, the Prix du Conseil des Arts et des Lettres du Québec 2024, among several other prizes and shortlist appearances. As of its publication, this English translation (by Quebec City-based translator Pablo Strauss) is on the Giller Prize long list, in a year where the prize has continued to be controversial. What I Know About You is an ambitious debut, spanning decades and continents, with several mysteries at its centre, not least that of its narrator’s identity. Its personal romances and tragedies are always foregrounded against and often in sync with the political upheavals of Egypt over several decades.

The narrative begins in the optimistic Cairo of the early 1960s, then moves through the disappointment of the Six-Day War of 1967 and the Fourth Arab-Israeli War of 1973, followed by the growing religious conservatism of the 1980s, with a dénouement set in 2001, somewhere between Egypt and Montreal. While this is ostensibly a queer novel that centres a forbidden gay relationship, it is also—perhaps due to the secretive nature of its central love story—a novel of distance, remove, emotional avoidance, missed conversations and unspoken desires. Sometimes this aura of remove serves the novel’s themes and questions—how much can we really know each other, especially within the confines of bourgeois expectations and repressive, homophobic attitudes? At other points, the novel ends up feeling overly distant from its own queer subjects—our knowledge of lovers Tarek and Ali and their affair is sketched out and tentative, imagined by a narrator who remains unknown for most of the novel. Often, because of this built-in distance in the text, its characters and their passions, fears and desires, are reported rather than embodied.

What I Know About You is narrated in the second person—a risky choice by Chacour, and one that establishes a mystery from the beginning, as there soon emerges an unknown “I” who is speaking to the “you” of the story. In the English translation, we are not quite able to detect the particular intimacy of the original French “tu” address. Chacour’s use of “tu” rather than the more formal “vous” implies a closeness between the “I” and the “you” that can’t be conveyed in the same way in English. “You” is Tarek Seidah, the son of an admired and successful Cairo doctor, and member of a bourgeois family that traces its roots to the Levant. This community keeps to itself, forming “a city within a city.” Known in Arabic as Shawam, these Christian Levantine Egyptians see themselves as closer to Europeans than Arabs, often speaking French more fluently than Arabic. However, despite their obsession with all things Western, they still blame homosexuality on European moral failings: gayness “is treated as a joke, a Western perversion, almost never a topic of discussion.” The “you” address contributes to the sense that Tarek’s life is under constant social surveillance, that someone is always watching—he is privileged by wealth and good career prospects, but his behaviour and choices must fit a proscribed path, and he must maintain the social standing that his father has worked hard for.

“When the two men first kiss, the unknown narrator is coy, withholding.”

Following in his father’s footsteps, less because he wants to and more because he feels he has to, Tarek becomes a doctor and opens his own clinic in Mokattam, a poor Coptic neighbourhood in Cairo. There, he forms a surprising relationship with a young man, Ali, 15 years his junior, whose mother has Huntington’s disease. Ali, talented and quick to learn, soon becomes Tarek’s assistant at the clinic. Their friendship slowly becomes a sexual and romantic affair, which is a problem, both because of the homophobia of 1980s Egypt, and because Tarek is married to Mira, whom, up until this betrayal, he appears to love and respect. In the company of Ali and his mother, Tarek learns to shed some of his bourgeois habits: “You stopped cluttering your sentences with platitudes. Freed from the constraints of propriety, you took time to answer her questions as truthfully as possible.” At one point, Ali’s mother asks Tarek whether her son is handsome. The narrator, not Tarek, notes “the fine line of [Ali’s] eyebrows and the sharp contours of his garnet mouth.” We are denied any sense of Tarek’s emotions here, which feels like a missed opportunity for interiority, for the beginnings of desire. We are only told that he responds, “You son is very handsome.” When the two men first kiss, the unknown narrator is coy, withholding: “His lips were touching yours. Unless it was the other way around. After all, how could I know?” Soon after this, when the two men begin to sleep together in secret, the narrator is similarly demure: “It’s not my place to say what happened that night … That part belongs to you, that’s all.” There is something dissatisfying about this—as if the homophobia the two men are hiding from is also permeating the text: the romance can be named, yes, but the sex must stay out of the story. Eventually, once the narrator’s identity is revealed, we understand that there is a good reason, other than homophobia, for this apparent prudishness—but it does have the effect of distancing the reader from the turbulent queer intimacy that ends up dismantling Tarek and his family, as well as Ali.

This is not to say that there aren’t passages of sensual immersion in these pages. We get to know the bustle of Cairo, the big apartment building owned by Tarek’s family, full of various family members visiting between floors, with his father’s medical clinic on its main level. The air is ripe with the scents of perfumes of the era. Chabrawichi 555, an affordable, zesty eau de cologne ubiquitous in Egypt at the time, is gifted to Tarek by the family’s live-in maid, Fatheya; Infini by Caron, a classic French floral perfume, is worn by Tarek’s mother, who is obsessed with all things European. In one scene in a hot parking lot, full of “Oily puddles with iridescent streaks in metallic hues,” one character “hopped around, in a miasma of gas fumes, like someone dancing atop an erupting volcano.” In another gorgeous passage, Tarek watches Ali’s gestures, while the two men are out together, visiting an underground gay bar that Ali knows of: “He sucked on his cigarette, which lit in two puffs. You watched how this manoeuvre hollowed out his cheeks, how the orange light coloured the veins on his hand.” Here, though, we still don’t have access to Tarek’s thoughts or feelings. The tender attention to the lines of Ali’s body says all we need to know. I found myself wanting to linger here, in scenes like this, where the dizzying pull of desire is both undeniable and bittersweet.

The delicate balance of love and lies cannot last long, though. Tarek and Ali are separated in a tragic series of events—first through the eruption of class conflict between the two men, fuelled by Tarek’s own shame, and then through a much more dire occurrence. After tragedy upends his life, Tarek abruptly leaves Egypt and settles in Montreal, where he builds his medical career back up from scratch, as a skilled immigrant whose credentials are not recognized by the Canadian system.

The second portion of the book reveals the identity of the narrator, which at first offers exciting narrative possibilities, but unfortunately, like Tarek’s new life in Montreal, the text loses much of its verve. Chacour can’t quite maintain the tension that simmers in the first half—we are even further from the heart of the story than before, and the text begins to overlap with itself, retelling various moments without adding much through the repetition. Tarek becomes even more unknowable to the reader: he is now in self-imposed exile from his home and his family, which could have opened up space for a reckoning of some sort, but instead, he becomes a blank, and the emotional stakes of the story begin to ebb.

Overall, and especially in its latter half, What I Know About You reads less as a queer love story than a tale of the silence and estrangement that the repression of gay desire can wreak. So much more of this novel is about the fallout of Tarek and Ali’s affair than it is about the relationship itself, which can’t even be named by its two members, and is rarely embodied in the text. In the world of this novel, queerness is absence—emotional absence, physical absence, the absence of family stories—even the absence of sexual intimacy, at least on the page. All these gaps are fitting, given the repressive setting and the guilt it engenders in Tarek, but it means that the queerness of two of the book’s main characters is buried for the reader in the same way that they must bury it in 1980s Cairo. At one point, the narrator asks, “From what depths had I summoned the arrogance to think I could anticipate your reactions when I knew nothing about you?” This summarizes a weak point of the novel: without interiority, Tarek is an unknowable cipher, both to the narrator and to the reader, and this means that his history, his desires, his love, his sorrows, all of which should form the centre of the story, remain out of reach to us, sketched out but never filled in. Because we only know Ali through Tarek, his character is even less filled in, except for a few brief moments where his boldness and his matter-of-fact understanding of the world break through, providing an important contrast to Tarek’s guilt-driven bourgeois attitudes and actions. This is still an impressive debut, and Chacour narrates the romantic, tragic and historic events of his tale with clarity and confidence. He deftly intersperses harsh realities with bursts of sensual detail; however, despite assembling all the ingredients for an engrossing story of love, betrayal and exile, he does not always manage to bring his characters to vibrant life.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra