It is the first anniversary of 9/11, and in the back row of a Quaker high school assembly to commemorate the tragedy, two bored high schoolers are waiting for someone to speak. Not for the sake of mourning—they are not interested in thinking about mourning—but for the sake of seeing who wins the 9/11 edition of their daily game: “Guess Who’s Gay.” Usually, their qualification to become “gay for the day” is just to speak in assembly, but under the circumstances, teenagers Fay and Nell—who refer to themselves as the “F&N Unit”—have altered the rules. “The first person to cry is gay,” they agree, while “the first person to laugh inappropriately is so gay that he or she will be counted as two gay people.” After all, they’ve calculated that there must be 19 other gay people at the school—so where are they?

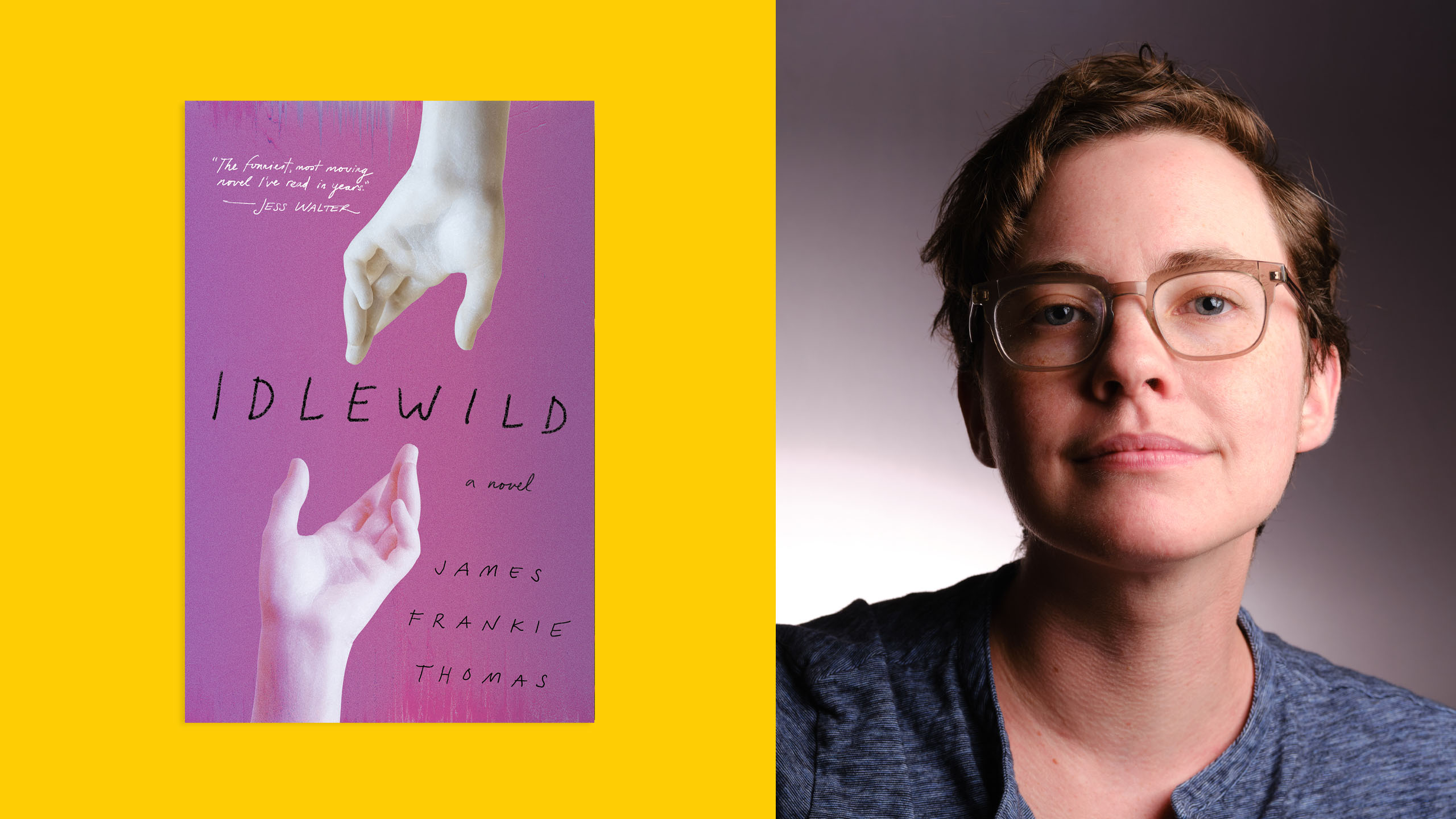

James Frankie Thomas’s debut novel, Idlewild, is a richly imagined portrayal of early-2000s adolescence, full of theatre drama, late-night fanfiction-writing sessions over AIM, endless caramel frappuccinos and queer yearning; within its pages, school is both an intense, life-defining experience and a quiet hell. Even in Fay and Nell’s cute assembly game, you can start to see the suffocating tension of their environment: their endless-yet-often-vague discussions of gayness are attempts to fight the crushing silence of their peers and parents on the topic, a silence that is driving them crazy. When Fay and Nell encounter two boys at school whose homoerotic tension is apparent, they both become obsessed, particularly Fay. But one of the duo can discern what makes Fay different from Nell—and it is that difference that threatens to tear everything apart.

Because the book is occasionally interrupted by flash-forwards to Nell 15 years later, we know from very early on in Idlewild that the F&N Unit is doomed to disintegrate, but we don’t know why. As we get to know Fay, Nell and their peers, sinking into the pleasurable colourwash of teenage nostalgia, we still never quite forget that everything is tilting toward disaster. This structure is a familiar one for the school novel: it’s reminiscent of Donna Tartt’s The Secret History—a book which, in Thomas’s words, is “an influence on Idlewild in the same sense that Shakespeare is an ‘influence’ on English theatre” —as well as several recent innovations on the genre, such as Susan Choi’s Trust Exercise and Micah Nemerever’s These Violent Delights. (A friend of mine, who read the book alongside me, also noted its affinities with John Green’s YA staple Looking for Alaska.) Many of these books pivot on a death or other violent event, which exposes the already-present fault lines in the characters’ lives. What differentiates Idlewild is that it uses a source for its fault lines that has been widely used elsewhere, but almost never acknowledged as such: the tragic material of repressed transness, and what repressed trans people do to try to cope. Idlewild may be the first non-YA novel about gay trans manhood. Full stop.

There’s nothing gay novelists are better at writing than intracommunity conflict; Idlewild’s conflict, though, feels new in how it delves into pre-gayness, and in just how unsparing it is toward both its cis and trans protagonists. To be explicit: Nell is an out lesbian and is obsessed with Fay, while Fay has one, single, annihilatory desire—to be a gay man. Once you realize this (and the novel deliberately avoids the cliché of the “trans reveal,” hence I’m not counting it as a spoiler), things like Nell’s quiet enjoyment of Fay’s “Jessica Rabbit–like proportions” under her baggy clothing grow new and sharp edges, as does Fay’s tacit knowledge of Nell’s interest in her. Without transness being available as a thinkable option, the only way Fay can access being seen as legitimately queer is to quietly refuse to dispel the idea that her and Nell might be, or become, a lesbian couple. Fay won’t let Nell say no to being a shield; Nell won’t let Fay say no to being a girl. Of course, neither of them know how to advocate for themselves, either.

But their conflict runs even deeper than this, because Idlewild is, unlike most school stories or “dark academia,” an intensely hopeful novel, charged by utter conviction that being gay—for all its trials—is great. Nell is immensely frustrated at her mother and therapist, both of whose polite silences rest on the idea that being a lesbian is something tragic, when Nell is actually “fucking psyched to be a lesbian.” Nell wants to get out, go to Smith College and start living. Fay, however, believes in 2002 that her life is already over: “What I wanted was not to watch a boy kissing a boy, but to be a boy kissing a boy. The former was achievable; the latter was not. There was no substitute. There was no consolation.” This is an emotional position best expressed by the trans gay canon, as fledgling as it is: the intense agony of not getting to be gay. If Fay could love Nell, she would win some consolations—recognition as gay, recognition of a more legible masculinity—but she can’t. Idlewild is perhaps most groundbreaking and uncomfortable as a trans story where it recognizes what this turns teenage Fay into: someone who is incredibly vulnerable, deeply self-centred and often cruel.

As the Fay-and-Nell story develops, Idlewild balances it by fleshing out the characters teenage Nell and Fay rarely pay attention to, carefully building a picture of how Idlewild’s students fail each other through a mix of inattention, self-interest and fear. The book lingers in the excruciating moments where characters see a signal that someone needs help, and choose, for various reasons, to ignore it; it refuses to invoke the shield of “we just didn’t know,” as the older Fay and Nell obsessively think about what they did know, but couldn’t—or wouldn’t—act on. The result is a book that is funny and characterful, but also intensely sad, full as it is of the question of whether we want to fix, forgive, steal back or abandon our teenage selves. Teenage Fay and Nell are intensely alive, confused, happy, unhappy, rarely seem to eat solids or sleep and hurt each other so continually they barely register it, even as they glow in the warmth of one another’s constant presence and attention. As Nell looks back 15 years later, she is struck by the same mixture of aversion and longing that we are: I know so much more now, but would I still go back?

In the end, Idlewild is much more than “just” a trans novel, a school story or any singular thing, but it does showcase two early powers of the trans novel: its capacity for tragedy in the big, awe-inspiring Greek sense, and its capacity for hope and humour, which never lets that tragedy become final. The school novel can often feel like a repository of adult grief more than anything else, but Idlewild cares about healing as seriously as it does about pain. I won’t say what happens to Fay or Nell—you should see for yourself. But I do think, often, about how trans people joke “could transition have saved her?” when they see someone who looks like a lost cause. It’s a joke, but it pulls at something real: transition can bring back people who are lost to the world. Every day someone emerges, blinking, into the sunshine again. Perhaps we can recover more than we know.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra