Jamie Diaz is a Mexican-American self-taught artist and a trans woman who has been incarcerated for nearly three decades in a men’s prison in Texas. But she’s more than the sum of her hyphenated identities; she’s also passionately queer, delightfully witty and unabashedly earnest. She’s a breath of fresh air who will hopefully be free soon—she’s eligible for parole in 2025.

Diaz has been honing her craft for half a century, but it’s only in recent years that her art has gained hard-won public recognition. Her debut solo exhibition of paintings and comix, Even Flowers Bleed, launched at Daniel Cooney Fine Art last year, garnering acclaim from outlets ranging from Them to Artforum to NBC News.

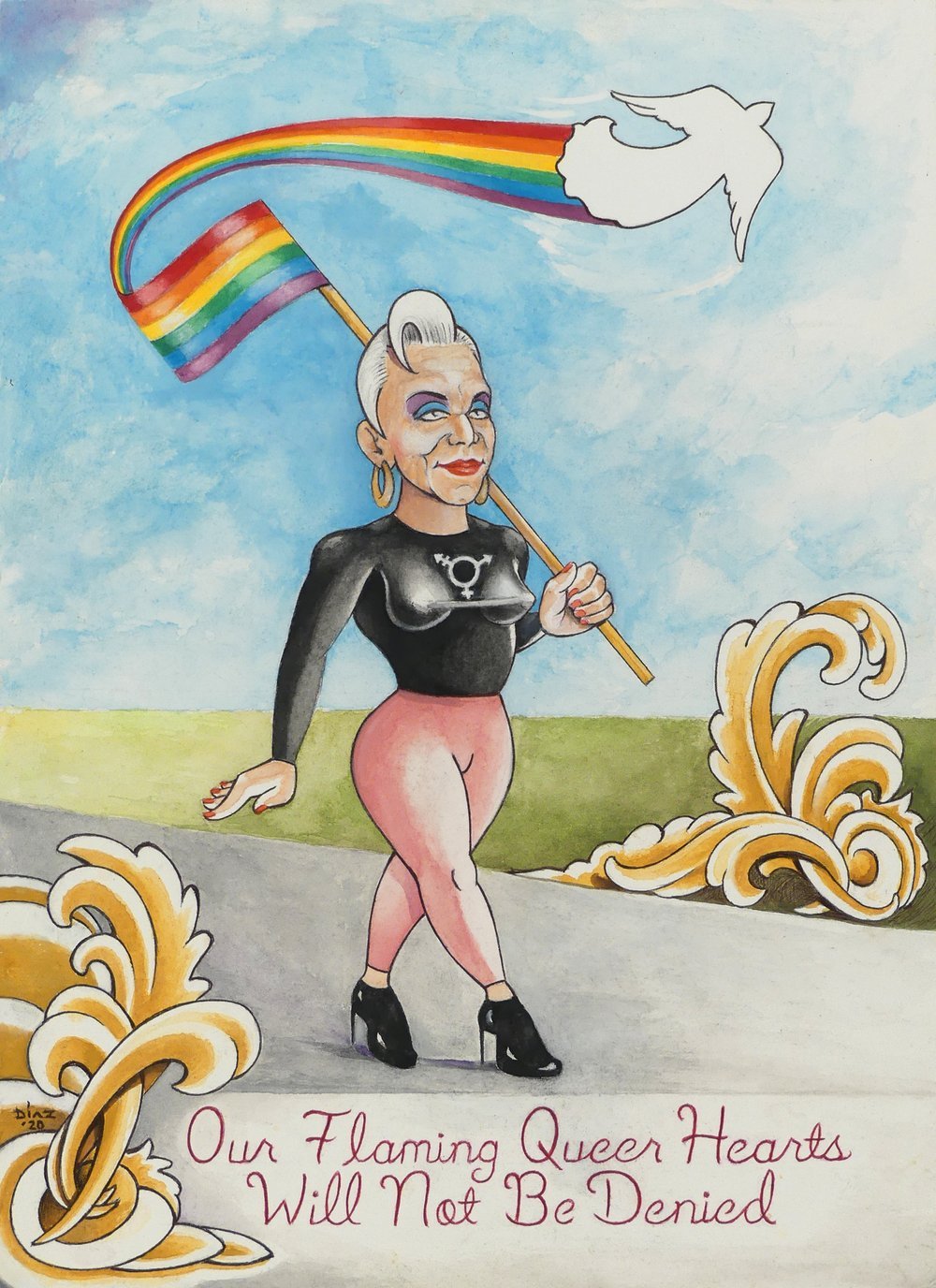

Credit: Jamie Diaz

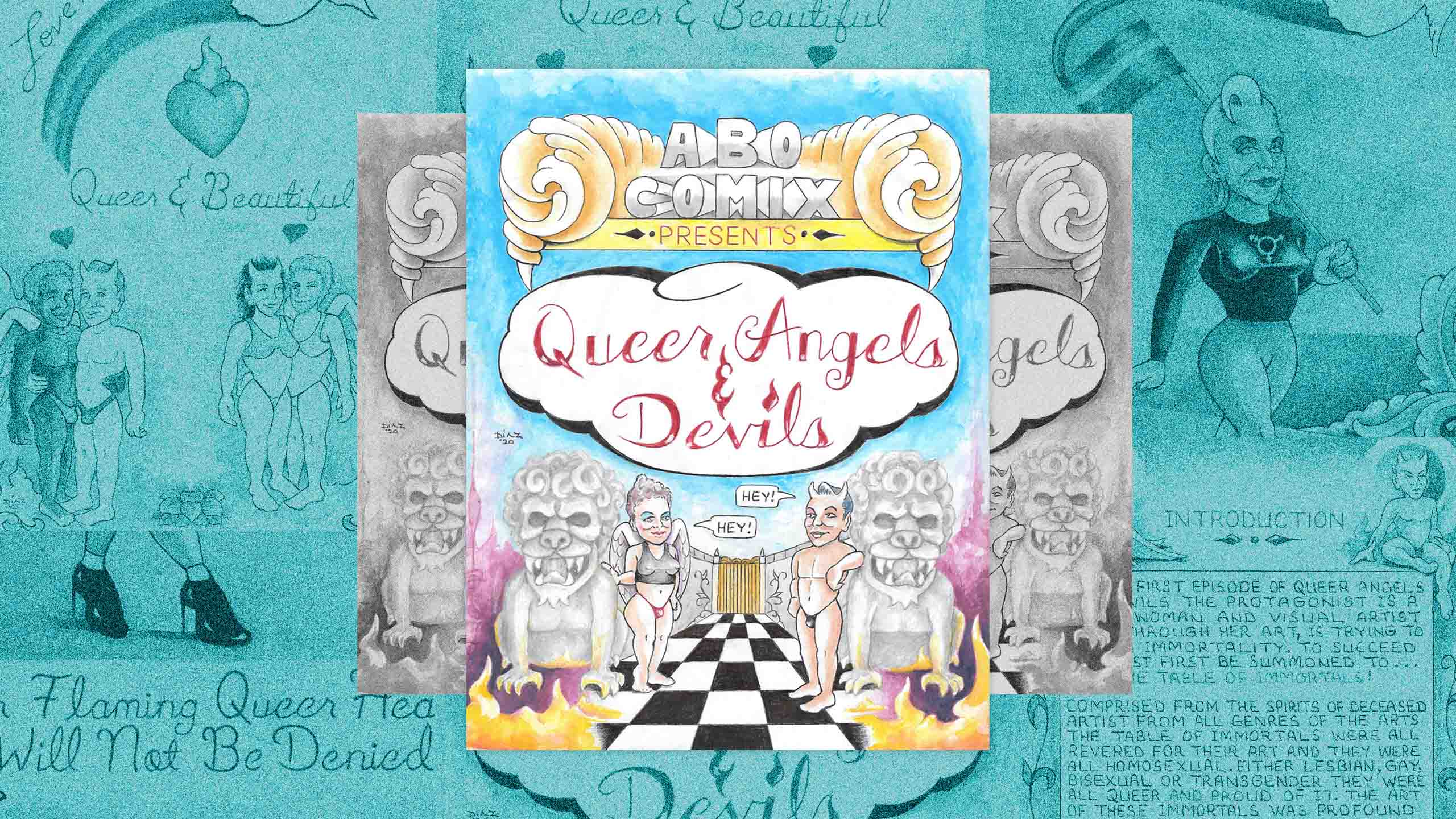

This month Diaz launches her first full-length book, Queer Angels & Devils, with A.B.O. Comix. Two years in the making, the book is a mix of autobiography and speculative fiction in which two time-travelling “little heathens”—delightfully, even the angels are heathens—are Diaz’s stalwart companions.

Gallerist Daniel Cooney was taken with Diaz’s work when he first encountered her website while researching incarcerated LGBTQ2S+ artists: “I thought her work was transcendent and fourth-dimensional,” Cooney tells Xtra. This otherworldly, ethereal quality that Diaz combines with the bodily (and the bawdy) has resonated with viewers.

Cooney says Diaz’s comix were “the most subversive in the show. They also reveal the optimism that makes her so incredibly special.” A.B.O. Comix co-founder Casper Cendre also praises Diaz’s comix work, saying it makes them smile “from ear to ear” and is “a testament to the humour, resilience and silliness that can be found even in the places we might think are the bleakest.”

Xtra spoke with Diaz in a series of phone conversations just before her book’s publication, which is available for pre-order here.

Can you tell us the short version of your life story?

I was born in Waukegan, Illinois, in 1958, and in 1963, my family moved to Houston, Texas. My childhood was magical for the simple reason that, by the age of 10, I was allowed to stay out until 10 p.m. and roam the streets. In 1968, my favourite song was “Sky Pilot” by Eric Burdon and the Animals—I used to run the streets with my transistor radio listening to it. I had a shoeshine box and I would go to bars and shine shoes for 25 cents. I encountered all kinds of people and had a blast. I was a happy little heathen, without a care in the world.

When did you come out?

I’ve been queer all my life, but I came out in 1973 when I was 15 because my mom discovered that I was using some of her makeup and clothes when I was at home alone. At first, I was afraid that I’d been “found out,” but later I was happy that I didn’t have to hide it anymore. Mom was very accepting of it.

Did you take up your artistic practice behind bars?

No. I also started to experiment with making art in 1973. So, I was already getting serious about it before I came to prison. I’ve been doing art for many years, and it still feels like I’m just now becoming an artist.

I love that your queer and artistic selves came out simultaneously. Can you tell us about the inspiration for Queer Angels & Devils?

I had been drawing these little cartoons of queer angels and devils on cards and letters that I sent to people—to all kinds of pen pals in the U.S. and even Europe—Germany, Croatia. I started about 20 years ago. I sometimes get fan mail from people who have seen and liked my art, and sometimes from fellow artists, and I’ve responded with illustrated letters. Many different people from all over the world have these angels and devils. One day I thought it would be a good idea to use these little creatures for comics—to start building stories around them.

Which comix artists have inspired your own work?

I love Robert Williams, who collaborated with S. Clay Wilson and Spain Rodriguez, who all appeared in Zap Comix. These guys are amazing artists and were really big in the 1960s and ’70s in the underground comix scene. Their work had a big influence on me. They are masters, and they put so much emotion into their work. And I love the work of Robert Crumb, creator of the Mr. Natural comix. Crumb sometimes used his own person as a character in his comics, and that’s where I got the idea to do the same.

That’s a great segue to my next question. You’re the protagonist of Queer Angels & Devils, and your inspiration or influence goes much further back than the underground comix artists you mention: your story riffs on the classic or mythic hero’s journey.

Yes. I’m on a quest to earn my place in the pantheon of queer artists. Those artists are my heroes and had a lot to do with my acceptance of myself as a queer person. I am both the classic damsel in distress and the hero of my own story—

—You can “save” yourself—literally: earn your immortality—while, in a way, you’ve already been saved or rescued by those queer forebears.

That’s right, and I want a seat at that table with them. I want to do my part with my art to help others in turn. I hope my work will influence other queer people in a positive way and give them pride and joy.

The artists—actors, painters, photographers, writers—that I put at the Table of Immortals are all real people who have lived before and left a legacy. They are immortalized through the work that they left behind. Artists like Oscar Wilde, James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, William Burroughs and Robert Mapplethorpe.

If you could have dinner and a conversation with any one of the queer artists who paved the way for you, who would it be and why? What might this dinner look like?

It would probably be Oscar Wilde because he was also incarcerated, and I love his work The Picture of Dorian Gray. It’s a fascinating story about debauchery and the macabre. He was imprisoned for sodomy—for being queer. I’d talk with him about that and about our experiences growing up queer—and about homosexuality and art and the relationship between the two in terms of culture and activism. I’d be so honoured to spend some time with him. I’d want him to be able to eat and drink whatever he desires. I picture us at a quiet piano bar with dim lighting.

That is a beautiful picture of intimacy and kinship. One of the preoccupations of the book is the question of—or possibilities for—queer futures. What are your hopes for your own future?

I’m working to present the queer community in the best light possible—to show the world and society in general that we are just normal people who happen to be queer. My main goal is to create the biggest queer art collection in the world. And to have more gallery shows and to make more comix—to just keep living and working for as long as I can. More of everything!

What are the benefits of being what we might call a late bloomer (pun on your beloved flowers fully intended)? What are the drawbacks?

I’m almost 65, but I haven’t slowed down. I’m still moving around and doing things I did in my 30s. The benefit of being a late bloomer is that I bloomed at all. Truly, there are no drawbacks for me. The past is the past and it’s gone. I feel so blessed and grateful to have blossomed at any age.

What’s it like to have your art exhibited and soon a book launched when you’re on the inside and can’t be at the openings or parties?

Not being there does not bother me at all because I’m still able to make art and to share it and that’s what’s most important to me. I’m honoured and grateful to be in such a position. But once I’m out, I’ll look forward to being with the art and meeting people. I think it would be a great experience to see my art being viewed. I’ll sign autographs.

Your friend Gabriel appears as a character in the comic book. I’m really drawn to and inspired by your relationship with them, inside and outside the book. The mutual respect and admiration between you is palpable. Can you tell us about how you two met and how your friendship grew?

Gabriel and I met in 2013 when they were living in Boston volunteering for Black & Pink, an abolitionist organization that connects LGBTQ2S+ prisoners in the prison system to people on the outside. I had sent an illustrated letter to Black & Pink to introduce myself and to ask to be placed on their pen-pal list. Sometime later, Gabriel wrote and expressed how much they liked my art and to thank me for sharing it with them. I don’t recall what it was I drew on that letter; it was definitely queer. A few weeks later, I wrote back to Gabriel with an elaborately illustrated letter and told them that I was capable of doing much more and if they would like, to give me a little time I would be happy to share the kind of art I really do with them.

That was 10 years ago, and we’re still at it. Our friendship grew from mutual interest and from our love and understanding of people like us. You know we are both queer and trans and we share many other common interests. Gabriel was a literature major, and I’ve been an avid reader since my early teens, and over the years read many of the classics of English literature. Gabriel would sometimes tell me about a book they were reading, and I’d say, “Oh yeah, I read that 20 or 30 years ago!” We were both very passionate about being queer and about our queer community as a whole in terms of support and well-being. We encourage and support each other. We sometimes refer to each other as each other’s COSMIC CONNECTION. Please put COSMIC CONNECTION in capital letters when you print this.

Gabriel’s quite a bit younger than you. I think intergenerational friendships are so valuable and so rare, sadly. As their queer elder, what do you offer Gabriel? And what do they offer you?

Gabriel is more than 30 years younger than I am. I don’t really feel that I have much to offer as an elder. We are not only friends; we are family. That inspires me to do the best I can in all things. Being close to Gabriel helps keep me connected to and current with today’s young adults. Gabriel has my complete trust and devotion. Everything I do is for Gabriel. I love them and want to do anything I can to make them happy. I’m not sure I would have even transitioned if it wasn’t for Gabriel’s love and encouragement. I was worried I was too old to do it—for the hormones to be effective. Gabriel thought I would benefit and that’s why I started, and it did.

If I understand correctly, Gabriel is your art rep, yes?

In terms of my art, Gabriel is my biggest advocate and has done more than anyone to help get my art some recognition in the queer community. They saw value in my queer art before I did. I mean, I love what I do, and I always thought the subject matter of my art was special, but I never thought so many people would like it so much. Gabriel got my art out there. If it wasn’t for Gabriel, there would be no Jamie. I wouldn’t have been so determined to keep pushing myself to get better if it wasn’t to do what I said I was going to do for Gabriel: to make them the biggest queer art collection in the world—and to make them proud of me.

Can you tell us a bit about your publisher, A.B.O. Comix.

They are a unique publisher. From what I know, Casper Cendre and a couple of their friends got together in Oakland, California, one day and had this idea to put out a comic book of art created by queer and trans prisoners. They put out a notice asking for submissions. That was five years ago, and in that time, I’ve had work featured in five of their anthologies. In 2021, I asked Casper if they would be interested in publishing my first full-length comic book and they said yes.

Queer Angels & Devils is autobiographical while also taking imaginative flights of fancy. There are no prison bars depicted, for example. Can you talk about the interplay of fiction and non-fiction?

The book is set in an imaginative future where I’m out and I’m living with Gabriel. A lot of the past and present is autobiographical—any named characters are real people—but that future, I haven’t lived yet. It documents how far I’ve come and imagines how far I can go. It’s a dream for my future. I want things to work out like I show them working out: for me to keep working and keep creating my queer art and for me and Gabriel to have a house full of friends and family—to create for ourselves our own little queer community.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra