Sol Giwa says he’s invisible. He says he feels it when he watches television and when he reads magazines. Whenever he sees gay culture represented, the faces of his community always seem to be white.

“When I go into the community, the racism I experience is not overt, it is very subdued,” he claims. “As a person of colour, I do not see myself being reflected in the agencies and issues in that community.”

Giwa says it makes him feel like he doesn’t fit and is not accepted within the community.

Giwa recently received a scholarship from the Lambda Foundation For Excellence, a respected Ottawa-based non-profit organization that promotes the achievements and culture of gay and lesbian peoples. Giwa says he was the only local scholarship recipient to attend the awards ceremony and yet his picture was not posted on the website. The organization did, however, upload pictures of the parents of a white man who was also honoured that evening but was unable to attend the ceremony.

“If you look at the website, it’s all white people,” says Giwa. “That’s invisibility. It’s not like they don’t have a picture of me to put on there. There were plenty of pictures taken. That is a missed opportunity for Lambda to advertise the diversity of the people receiving the awards and the diverse [community] members who are making inroads in gay and lesbian studies.”

Replies Bill Staubi, who organized the Lambda evening: “It’s a fair comment.

“In terms of that particular event, we hadn’t thought of that element. If we had, we would probably have tried to take his picture earlier.”

Staubi explains that Giwa left the event before Lambda photographers took photos of participants. Organizers should have done a better job of co-ordinating with Giwa to ensure they got his photo, he says. And he agrees that the gay community must make more of an effort to reach out and embrace the full diversity of minorities within.

“It’s ironic,” says Staubi. “You’d think in our community we’d be really aware of it.”

***

Giwa has another example: a recent job posting for a volunteer coordinator position at Pink Triangle Services that he found on charityvillage.com. A note near the bottom of the job posting stated: “We encourage women, people with disabilities, First Nations, gay, lesbian, bisexual and self-identified transgendered to apply.” People of colour were absent.

“Again it shows the invisibility,” explains Giwa. “It is 2005 and Pink Triangle Services is supposed to be the pinnacle for gay issues and services to the gay community. I’m sure they are aware of the kaleidoscope within the community and people of colour are part of that as well.”

Michelle Reis-Amores, the new executive director of PTS, offers “an apology on my part” if the ad appeared without an encouragement for people of colour to apply.

Speaking generally about organizations, Reis-Amores says encouraging multiple diversities is “not always foremost on their minds. It should be.”

From what she’s seen, PTS is trying to attract “queer people who identify as non-mainstream.” Next month, for example, the organization is going to amend its mandate to reach out to trans and two-spirited people.

And PTS walked its walk when it hired her, says Reis-Amores, pointing to her own multiple identifications with the queer community, minority language communities and her partly Spanish and Lebanese heritage.

But Giwa says the issues are often ignored. When he decided to do some research on the topic for his Masters Of Social Work, Giwa found there was scarce literature on invisibility and racism within gay and lesbian culture. Giwa says it points to a lack of priority for ending racism and oppression.

“The [gay, lesbian, bisexual and trans] community is not proactive around this issue,” he says. “There seems to be a silence when it comes to identifying and confronting racism.”

Many people may see the issue of diversity within the gay community as too overwhelming a problem and do not know how to start tackling it. Giwa says the key is to start with organizations and services within Ottawa. When they make diversity a priority, then people in positions of power must educate themselves and take accountability.

“Some people would say, ‘If people of colour are not showing up to a publicized event, then that is not our problem,’ but you have to look at the issue historically,” he explains. “What have we been doing in the past and how does that bring us to where we are now? Historically, people of colour have been excluded from participation, but in 2005 we are expected to come out to events. It does not work like that.”

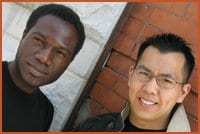

Darryl Lim, programming coordinator for the queer students’ centre at Carleton University, agrees. The GLBT Centre is a good example of how community groups can create a culture of diversity, he says. Lim and his co-coordinator are both people of colour and the centre itself is made up of 30 to 40 percent diverse members, which includes people of colour, people of different abilities, transgendered people and members of different religious backgrounds.

Lim says that diversity can become tokenized.

“Ten white people and one Asian person does not mean your organization is diverse. I believe diversity has been achieved when an organization doesn’t have to make reference to their diversity, when it is just not an issue anymore.”

Because of the Carleton centre’s diversity, they are able to take on issues and topics that many other group have not, such as intersexuality and multicultural programming. Lim says the diverse culture breaks down stereotypes and barriers for every member of the centre.

But if an organization approaches diversity in the wrong way, it can be very destructive, says Lim. Members of the group may feel tokenized and feel like they are being asked to represent their race.

“I hate being referred to as Darryl Lim, the Asian programming coordinator. That is not how I define myself.”

Lim says the best place for organizations to start is to create diverse policies, including hiring policies.

The University Of Ottawa Pride Centre has diversity policies in place already through their membership in the U Of O student federation, says service director Joel Guenette. The Centre also has policies around acceptance of diversity within hiring practices, work environment and volunteering. But right now, diversity is not the focus.

“We are focussed much more on sexual diversity day-to-day than racial diversity,” Guenette says.

But that’s not enough, suggests Giwa. People cannot sit back and hope that change will occur without action.

“If you look at everything that has been written on the topic, it has come from people of colour, but remember that these people do not have power within the culture. It takes everyone, black and white people, to shake the foundation apart. We need representation from the whole kaleidoscope.”

This also includes networking with groups outside the gay and lesbian community such as media companies, television stations and mainstream service groups, he adds. It is necessary to build partnerships and bring the Ottawa community at large into the discussion.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra