In the 1960s, Thomas Pynchon befuddled America with his debut novel, V. The tome was a lengthy, dense and largely inexplicable saga of a man as he undertakes an obsessive and increasingly frenetic search for a mysterious entity he knows only by the letter “V.” Six decades (and two letters) later, Davey Davis’s X explores similar themes for a very different epoch. Like the Cold War America of Pynchon’s V., Davis’s America is in the midst of a social, political and cultural breakdown—a breakdown that acts as backdrop and propellor for a quest undertaken by a neurotic protagonist chasing some kind of salvation. Or at least a way out.

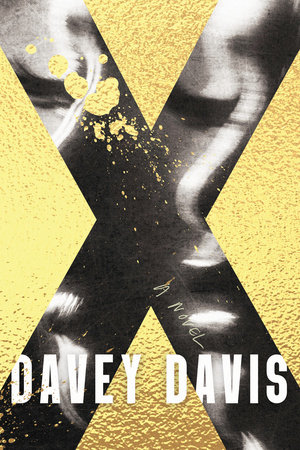

Credit: Courtesy of Catapult

X, Davis’s second book following 2017’s the earthquake room, was published last month by Catapult Press. The novel follows the misanthropic, cynical and largely unpleasant Lee as they attempt to survive in an alternate present (or near future) Brooklyn. Rent’s going up, the surveillance state is expanding and the police are squashing protests with unnecessary force. All of this is, of course, par for the course. But then there are the ominous letters that anyone vaguely interesting (queers, criminals, political dissidents) receive in the mail from the government, advising them to leave the country at once, as part of the “export program,” or face consequences. No one knows what’s really happening behind the scenes in the export program—do the exports arrive safely at their destinations? For what reasons are they asked to leave?—but what’s certain is that when you receive a letter, you’d better start getting your affairs in order to leave.

Lee isn’t trying to leave, but they’re looking for some kind of an escape. They spend their days being cheated out of paycheques at their job, their evenings crashing on a couch they rent in their friend’s apartment. All the while, they’re haunted by a recent breakup and by a childhood marred by sickness and abuse. Through all this they’re kept afloat by the city’s queer BDSM underground—Lee’s a true sadist, and there’s nothing they love more than inflicting pain on their sexual partners. At least, that’s what they think until they meet the mystifying X. After a sexual encounter that bores a hole into Lee’s unconscious mind and upends their psyche (and world), they become fixated on finding X again before she exports: “As the wind picks up, the streets empty. It’s a relief, and not just because I hate people. I’ve started seeing X. I mean, it’s not really her. The first time I thought I saw her, when I rubbed my fists in my eyes like Ebenezer Scrooge and looked again, she had melted into the lens of the surveillance camera above her head. I wish I’d never met her. I wish she didn’t exist. People who don’t exist can’t export, after all.”

X is a tale of personal, relational and political turmoil, and the ways the three fields intersect, entwine and propel each other along. From their home in Brooklyn, Davis spoke with Xtra about interpersonal violence, the pain/pleasure binary and femdom nightmares.

What was the impetus for the idea behind X?

The origin is pretty diffuse, but I would say the kernel of it came from Christopher Isherwood’s works. I had read a bunch of them, especially Berlin Stories, when I first started putting my notes together for X. I was really interested in the ways a government can exert pressure on different populations. Isherwood was writing about Weimar Germany, and how certain populations were encouraged to leave the country before they were forced to, or put in camps. That was something that grabbed my attention, and I was thinking about what that situation might look like in a different context.

At the same time, I wanted to write about my femdom nightmare. So that political background became the backdrop for a character who encounters a femdom nightmare and what happens to them as a result. This protagonist, Lee, thinks of themselves as a sadist top before they meet their femdom nightmare named X; she throws everything into question for them. I think of X as a character, but she’s also a cipher and a force. I think of this novel, and a lot of my writing, in very cinematic terms, within which X is the femme fatale and the movie monster at the same time.

What is nightmarish about the character X? Lee seems to be really magnetized by her and appears to enjoy their encounter to some extent.

Absolutely. But within femdom specifically, the femdom figure is a fantasy. The appeal and fascination of that fantasy doesn’t mean that it’s one-dimensional or conventionally good or beautiful, appealing or sexy. This fantasy can also be scary and challenging. So when I say “femdom nightmare,” it’s kind of tongue-in-cheek, but it’s also just the territory of femdom; it’s scary.

Against the backdrops of the political circumstances and the femdom nightmare, where did the protagonist, Lee, come from? How did they fit into the political situation you wanted to describe?

I really liked the idea of creating a character who was unfamiliar to me. A character I didn’t have a lot in common with, whose motivations I might understand, but that I don’t share. For me, Lee’s character was a practice in difference. I’m also interested in the ways regular life carries on against the background of crisis, in what interpersonal crisis looks like against a background of geopolitical and climate crisis, which is something that comes up a lot in my work for what are obvious reasons. And the ways we metabolize these greater-scale crises filter through in our own lives, through our neuroses, anxieties and fears. These very real political pressures are experienced and exerted differently on all of us at the individual level, and I’m interested in how that plays out across the larger political landscape.

While you were working on X what was your life and writing process like?

I wrote X over the span of about eight or nine months in 2019. I had just moved to New York from the Bay Area. I had both a full-time and a part-time job, but I was really just in writing mode—I was writing constantly. I was adjusting to being in a new place while trying to write about this new place that I didn’t know very well. So it was kind of a grind. But I’m a grinder and I like to work.

Usually my writing process was to get up before work, get in a couple of hours, and sometimes more after work. I don’t like having a job, but I freelanced for a long time, and the nice part about having a stable job is that it makes it easier for me to have a stable writing schedule, which has been really productive.

What was it like working on prose featuring significant amounts of violence and sadism?

Anyone who reads or follows my work knows that I have a strong interest in fantasy, sensation and the body. I used to work more in body horror. I guess this book would fall under that category, though I’m moving away from that in my fiction. I’m very interested in physical sensation and experience. In my nonfiction, I write and think a lot about the pain-pleasure binary and how I think it isn’t real.

I write a lot about physical violence, and it’s true that X is very violent, but I think it’s just as much about pleasure and sensuality. Often what looks violent or reads as violent is not merely violence. I’m interested in violence as a spectrum or as an experience that can be more than one-dimensional. The way Puritan American sexual mores are, and the way that pleasure’s commonly thought of, is that it’s relegated to these different areas: that it’s only sexual, for example. We don’t often devote much imagination to what pleasure can mean. And the fact of the matter is, people take pleasure in lots of different things, for lots of different reasons. People take part in painful, stressful or endurance-based activities, and do it because they want to— they take joy or satisfaction in it, and they get something out of it.

The idea that pain is only one thing, pleasure is only one thing, and they’re only experienced at certain times, in certain ways, for certain reasons and at certain sites on the body, is something I think we should denaturalize—if only because it gives you a much more interesting engagement with your body.

Within X’s plot, events can be unclear because we’re seeing things through Lee’s point of view. What were you trying to accomplish with this highly subjective, unreliable narration?

I think what a character knows, and what a character allows themselves to know, is information for the reader. There are direct and indirect ways of sharing, and a character’s mental state can be written in a lot of really different ways. One of those ways was showing the reader in certain ways what’s kind of going on in Lee’s world, and making people work for it a little bit, leaving room for interpretation and ambiguity.

There’s a lot in X about nature-versus-nurture theories of queerness, the different schools of thought around whether queer people are born that way, or whether they become that way through the circumstances of their lives. Lee seems to mock both theories. What would be an alternative?

One thing that Lee and I share in common is frustration with the question of where queerness begins. The purpose of the question is not actual enlightenment or knowledge, or even a better dissemination of resources or medical care on a structural level. The purpose of those inquiries is to find a way to eliminate queer people. It asks, here’s the problem, what’s the solution to the problem? Like the scientists who wanted to isolate the trans gene—I don’t think we need that.

Lee and I share a suspicion of what is essentially a eugenics-based perspective on queer and trans people as aberrant or anomalies or natural. Whether they think they decide to think that you’re special or not, it really comes down to thinking of us as freaks. I think the alternative to nature-or-nurture theories would just be, again, denaturalizing these categories and then focusing more on making sure people get what they need.

Within X, Lee describes their transition in terms of being perverted and desiring self-mutilation. What was behind that approach to queerness/transness?

A lot of people now recognize that the ways liberal movements recognize, or grant access to, queer people is conditional. Queer people can get what they need if they’re willing to play ball. And we all do. People are going to do what they need to get the shit that they need. But there’s an expectation that we’re supposed to be grateful for that. Lee recognizes how cynical and harmful that actually is. It’s a smokescreen for a respectability politic that is inherently imbalanced and that will box out certain kinds of people. It’s something that deserves Lee’s disdain, distrust and fear.

Lee will be cynical of things like the exporting program or racial and economic justice. But they also seem unempathetic and misanthropic. What’s with that discrepancy?

I wouldn’t say that Lee’s unempathetic. I tried to write Lee as a good sadist, and a good sadist is extremely empathetic—a person who’s very good at reading other people. They’re at their most human when they’re connected with other people, which, granted, is something they struggle with. There’s a lot about Lee that maybe makes them a shitty, untrustworthy or inconsistent person. But I don’t think that they’re a bad person.

When I was writing this book, my main motivation was to explore what makes people hurt people that they love and care about. Abuse happens all the time between and among people who have love, affection and intimacy for each other. The figure of the “predator” or the “abuser” or the “violent person” is something that needs to be deconstructed and destroyed in my opinion. All that does is create a category of bad person, and that kind of person doesn’t exist to me. Lee is cynical, and is definitely misanthropic and nihilistic. And Lee’s also a person who loves and is loved by other people, who is justifiably suspicious of the system, and who has their own biases and shortcomings.

In social justice parlance, Lee has a lot of unpacking to do on their own that they’re probably not interested in doing. Nonetheless, social justice language and awareness is the stuff you absorb if you’re on social media and in certain kinds of queer circles. It’s the kind of stuff you’ll be absorbing, and to an extent maybe even parroting—even if you’re not actually doing the work.

This is a big question, but: how can we work to prevent abuse and violence within the queer community?

Part of what’s really useful about SM as a metaphor in a book like this is how it can be used to explore the meanings of terms like consent, abuse and violence. The meanings of those things can often be unclear to people, especially when things get complicated within interpersonal relationships.

Especially as queer people, things get complicated with the mental health issues that come from everything from trauma, to sustained lack of access, to deprivation on a community level and structural neglect. How can we stop abuse from happening? I don’t know the answer to that. But I think the start of that would be not deciding that certain kinds of people are abusive, or that abusive behaviour isn’t something that everybody can do. Let’s start there, instead of deciding that you can categorically say whether or not someone is safe.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra