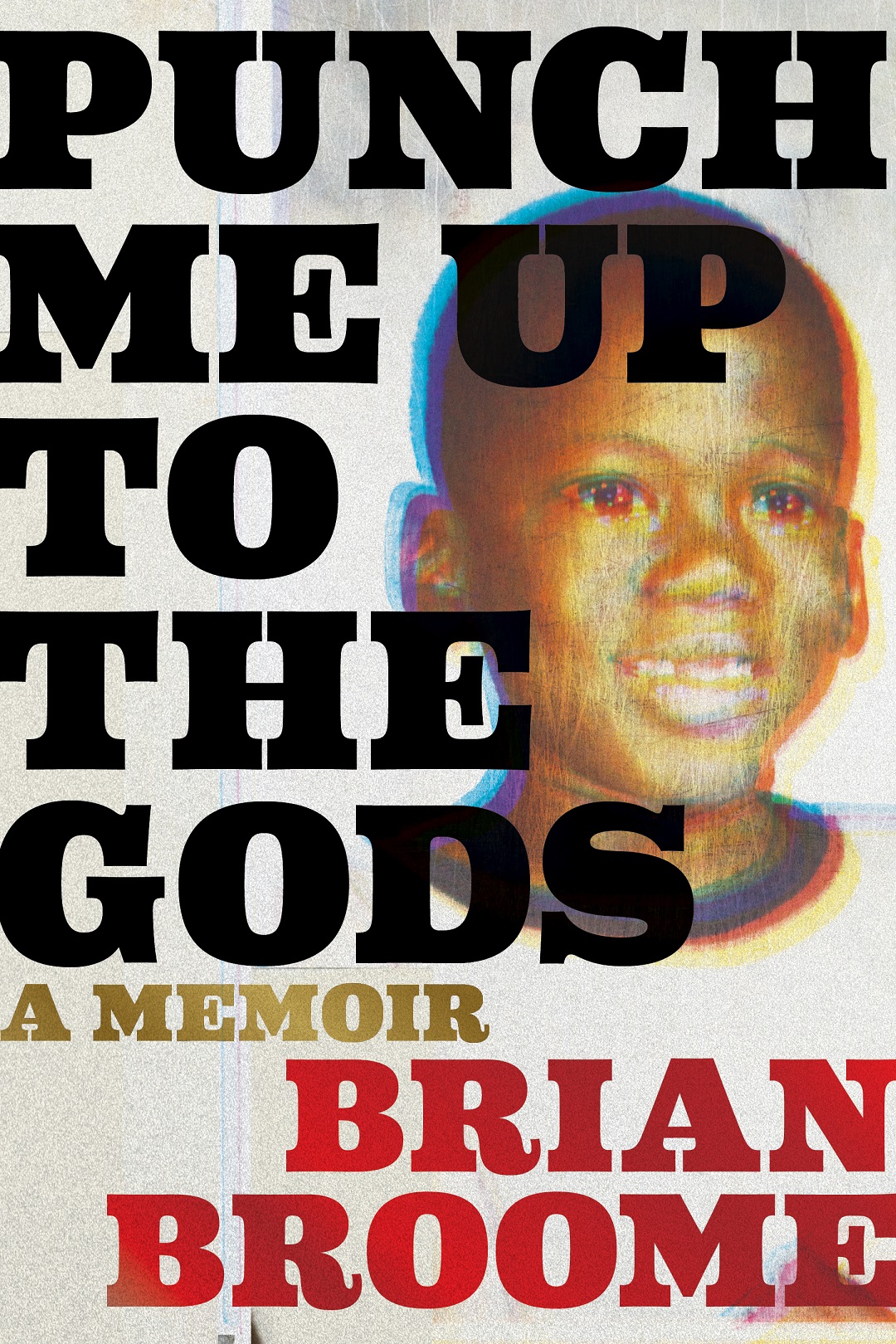

For anyone that has grown up gay and sensitive, it’s easy to recall the words that hurt us the most. Many of the words, especially from those we love, are the words that shape who we are and often shape how we feel about ourselves. In the case of Brian Broome, his memoir Punch Me Up to the Gods was a way for him to reclaim power over the pain that came with many of the words people used to try to destroy him.

For Broome, borning in Ohio but now a Pittsburgh-based poet and screenwriter, paring down his thoughts on manhood and the toxicity that lives in heteronormativity was something he knew would help heal old wounds. But his story isn’t just about him—it’s about giving voice to the struggles that young queer Black men have in their coming of age and the roads they must take in order to master the challenge of self-realization and liberation.

However, Broome had challenges on the road to freedom. From battling drug and alcohol addiction to spending several stints in rehab, his story exposed us to the hurtful words he internalized from both society and his family, words that almost ended his life. Moreover, his memoir highlights the struggles that queer Black men had in generations had before now, reminding the reader that sometimes we have to reinvent ourselves in order to give ourselves the lives that we deserve.

I spoke with Broome to discuss what life has been like since releasing the book, which came out in May, and what he has learned from the journey. We also talked a little about what he has learned in the months since its release and why the book is so timely in a time where so many Black queer people feel hopeless.

While I have to admit that reading the book was a bit hard for me at times, it really helped me come to contextualize so many things about my own healing journey. It helped me understand the ways in which homonegativity and white supremacy impact me and why it is so important for me to not only rewrite my own narrative, but to own the pain that comes with it.

In our conversation we took some time to discuss the importance of self reflection and why in the age of this pandemic, it is such a significant idea for Black queer people to find the time to heal, by any means necessary. As someone who has spent a lot of time interrogating Black masculinity, homophobia and the impossible expectations put on me by society, this book gives Black people the armour and the protection they need to survive in this world.

I wanted to know first what led you to say, “I am going to put all of my experiences (even the hard ones) down in a book?”

I was in rehab when I started writing and then there’s nothing like being in rehab to make you think about the choices you’ve made in your life. To just start re-evaluating things and trying to sort of figure out how I got there. When I first got there, I was like a lot of people in the sense that I didn’t believe that I needed to be there. It was all a mistake. Everyone is overreacting. But after a while, I did realize that I had a pretty bad drug and alcohol problem. So I sort of decided that I would start writing about how I got here and about the stories that started making me hate myself and the stories that made me so dependent on alcohol and drugs. Being in rehab and reflecting on life and reflecting on how much time in my life was really wasted.

You talk about survival and self-discovery a lot in your book. Is there anything specifically that you have learned about yourself in the process of this book being released?

Well, I am certainly glad to be here. Considering all the forces in the world that were telling me that I was not supposed to be here, such as I am. There were just so many cycles of people telling me that I was born wrong. Whether from racism or from homophobia, the cult of masculinity or whether it is just whatever. I can say that from writing this book, I am so much stronger than I think I am or than I thought I was, considering the fact that I am still here. I had contemplated killing myself so many times and many times that I had tried to, I’d end up in a psych ward just from depression. So if there is anything that I learned, it’s that I am stronger and that I don’t have to spend time flogging myself for being who I am.

So your book and its themes hint a lot at topics related to intersectionality. How does a person centre joy, relentlessness and resourcefulness while looking at all the forces that are up against you?

Wow. That’s a tough question. I guess I wanted to put them into the world as cautionary tales. I want people to read them and with the subtext of me saying, like, “Please do not be like me.” “Please do not sacrifice yourself like I did” on the altars of heteronormativity and homophobia and racism. The underlying message by the end of the book is that we do reach a joyful place. It’s that sometimes you go through a lot of things and joy comes at the end. That’s the central message of the book.

That is so important. Thank you for noting that. So I am always interested in learning what keeps someone in the book writing process. What was that “thing” that kept you writing even when it got hard?

You know, I’m going to be completely honest. One of the reasons is that we were in a pandemic and I couldn’t go anywhere. But I think what kept me writing was that there was a fire under me and I really wanted to get it done. I had to unburden myself of these things. I have to unburden myself about what was done to me and what I did. I was just tired of just lying all the time. That’s one of the things that they tell you in recovery is that you’re only as sick as your secrets. I had been sober for a while and I wanted to stay that way. I think that the biggest driving force behind keeping me writing was the desire to stay here. So, as I was writing I was thinking about drugs and alcohol less and less, to the point where I wasn’t thinking about it at all and all I was thinking about was writing. So I was writing to save myself.

That is so powerful. I know you’ve said in other interviews that your family might feel a certain way about some of the writing in the book. How have your family and friends responded to it?

I’ve gotten a lot of supportive feedback from people who have read the book, but I’ve also gotten terrible emails from people calling me a bunch of different names. That doesn’t matter to me. My mother did read the book and she called me to tell me she loved it. We are now able to talk about things now that we weren’t able to previously. She knows me more. And there are some things that she feels bad about. But I told her she didn’t have to apologize. That she didn’t have to feel bad. So in a lot of ways the book has brought us much closer because we can now have a much more open dialogue about what happened in my past.

This has been fantastic. Any last words you think are important for readers to know?

I just feel like I think one of the central messages of this story is that while it seems cliche, don’t let anybody else tell you who you are or how you should be. Those people are doing it only to make themselves more comfortable in the world. It has nothing to do with you. Don’t live in shame. Love those who love you. That’s the biggest message.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra