Sixty seconds and a drop of blood.

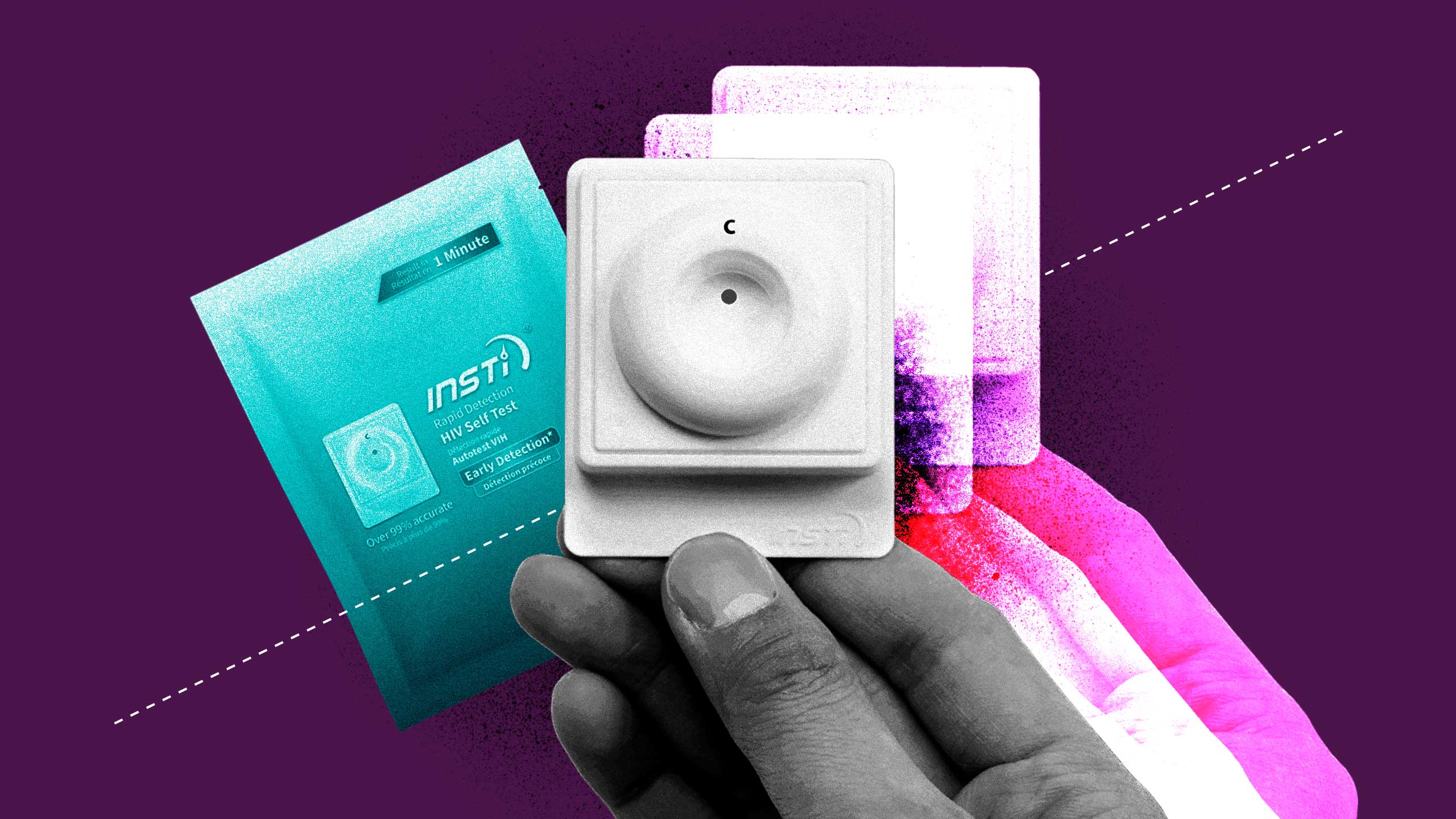

Those are two of the three things needed to produce a positive or negative result on Canada’s first and only HIV self-test, approved for public use in November 2020.

The third? The test itself: INSTI from British Columbia-based biotech company, bioLytical Laboratories. Well, that and the $34.95 it takes to order the kit (taxes and shipping not included).

For some, the price is well worth it. It’s been 35 years since the first commercial blood test for HIV was licensed in America. The fact that Canadians can, in the comfort of their home, prick a finger and find out their status is somewhat a marvel—especially now, as the country grapples with rising HIV transmission rates and a pandemic making lab testing less available. With gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men making up half of all HIV cases in Canada, as well as half of the country’s new cases, more options for testing is a good thing.

But will HIV self-tests prove to be worth the wait by helping reduce HIV transmissions? Or will the same factors that slowed the progression of self-testing in Canada prevent tests from getting into the hands of people who need them most?

What are HIV self-tests?

The INSTI HIV self-test—along with most self-tests—are antibody tests, meaning that what’s being detected isn’t the virus itself, but the body’s immune system response to it. This explains why INSTI recommends waiting between three and 12 weeks after a possible transmission to take the test (though anyone who believes they’ve just been exposed to the virus should immediately contact their doctor or go to an emergency room and ask for post-exposure prophylaxis, or PEP, which can prevent transmission if taken within 72 hours of exposure).

“A positive or negative result is shown to 99.5 percent accuracy.”

Not to be confused with “self-sampling,” where testers collect blood samples or other genetic material at home to send to a lab, self-tests produce a rapid result. The kit itself includes the test device, three bottles of liquid solutions, a lancet and a bandage, as well as instructions and other literature. Through various stages of mixing a blood droplet with the three solutions, a positive or negative result is shown to 99.5 percent accuracy.

How self-tests can help prevent HIV transmissions

With effective treatment, the amount of the virus in someone’s system becomes undetectable and, therefore, untransmittable (what’s referred to as “U=U”). As such, the more people who know they have HIV and access treatment, the closer we are to stopping its spread.

That’s the founding principle behind “90-90-90,” a set of goals outlined by the United Nations and signed onto by Canada: Have 90 percent of people with HIV aware of their status, 90 percent of them on treatment and 90 percent of them at an undetectable viral load by 2020.

Because of the Public Health Agency of Canada’s release schedule of data, we won’t know for another year if Canada did indeed hit all three targets last year, but recent trends suggest not. For instance, between 2016 and 2018, the percentage of people living with HIV who knew their status grew by just one percent, from 86 to 87 percent. This means that around 13 percent of people with HIV—or an estimated 9,000 people—do not know they have it. But self-tests can help address that disparity.

“Studies have found that the availability of HIV self-test kits leads to greater testing in the populations that need it,” says Sean Hosein, the science and medicine editor at CATIE, a national source for HIV and hepatitis C information. For instance, a 2019 American study recruited about 2,600 gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men and gave half of them HIV self-test kits. By the end of the study, participants who received kits self-tested themselves more frequently—on average five times, versus twice in the control group. People with kits also passed them along to partners and friends, meaning that more previously unknown cases of HIV were discovered.

“Studies have found that the availability of HIV self-test kits leads to greater testing in the populations that need it,”

Such results reinforce similar research done in the United Kingdom, Australia and parts of Africa, where participants appreciate the independence and privacy of self-tests. Because HIV risk is so linked with homosexuality and drug use, stigma makes it difficult to ask for testing from family doctors. Likewise, pop-up or anonymous HIV testing services aren’t offered in more suburban, rural and remote communities, so self-tests increase accessibility to accurate and anonymous testing.

“When you’ve got privacy, convenience and speed, it’s very attractive to people who wouldn’t typically access testing,” says Hosein.

The long road to get self-tests approved

The INSTI HIV self-test may look familiar to anyone who’s done a rapid HIV test at a clinic in the last 15 years, largely because it’s the same test.

“bioLytical’s test had been licensed in Canada for more than a decade, but they hadn’t yet brought forward a self-test version,” says Dr. Sean Rourke, a scientist at the MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions at Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital. “So we helped the company bring forward an application to allow the test to be done by everyone.”

Rourke’s mission to get at least one HIV self-test on the market began five years ago, when he published a white paper on the issue and tried to get the federal government to sign on, with little success. “There was no traction, it was just striking to me. Where was the leadership?”

Tired of waiting for a government mandate, Rourke and his colleagues formed REACH Nexus, a collective dedicated to ending Canada’s HIV epidemic by 2025 using tactics like self-testing. Their first step was to get the INSTI test approved for use by non-medical professionals, which they did by giving self-tests to more than 700 people from higher risk demographics—like men who have sex with men, injection drug users, Indigenous folks and immigrants from countries where the virus is prevalent.

The goal: Prove that people could be trusted to reliably take the test and interpret the result. By the study’s conclusion, more than 95 percent of participants said they’d use the self-test again and would recommend it to sexual partners, friends and others.

If proving that Canadians could follow self-test instructions sounds like a somewhat low-bar, that’s because it is. “There’s an element of paternalism—that health systems and doctors know better,” says Rourke.

For instance, HIV tests used to be accompanied by hour-long counselling sessions. However, now that so much more is known about the virus—and that treatments allow people to live long, healthy lives—the “looking over the shoulder” approach from health care practitioners isn’t needed, says Rourke. “These antiquated policies shouldn’t be there anymore.”

Canada’s delay in delivering HIV self-tests seems even more incongruous when compared to the rest of the world. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved its first over-the-counter HIV self-test back in 2012. In 2016, bioLytical’s INSTI test gained European approval—the same year that the World Health Organization endorsed HIV self-testing as “an empowering and innovative way to reach more people with HIV.” By approving INSTI for self-use in 2020, Canada finally joined nearly 80 countries who already had HIV self-test policies—the last G7 nation to do so.

The future of HIV self-tests

The INSTI tests themselves, however, have limitations.

“There are about a dozen tests better than INSTI, in terms of design and functionality, that should be approved in Canada,” says Dr. Nitika Pant Pai, a researcher and associate professor at McGill University who has developed a global phone app for HIV self-testing information.

For example, OraQuick—which has been on the market south of the border since 2012—uses an oral swab rather than a finger prick to detect HIV and is therefore less intimidating to anyone uneasy with drawing their own blood, says Pai. There’s also the U.K.’s BioSure, which uses a blood drop like INSTI but involves fewer steps, making it easier to follow. “The simpler for the end-user, the better.”

Cost is another barrier. Canada needs to not only approve more tests but also pay for them, says Pai. In Brazil, for instance, multiple HIV self-tests are on the market, each heavily subsidized by the government and available for free at various locations, like pharmacies. This is especially important when considering the groups at higher risk for HIV—like queer men, Indigenous people and injection drug users—may be less able to afford self-tests while simultaneously being less trusting of local health care agencies to request tests. Pai says these are exactly the groups self-tests can help reach, and why governments should prioritize spending here. “Whenever [governments] say ‘we don’t have money,’ that’s when they have money.”

Rourke agrees. “Governments will say we don’t have money to pay for it. Well, find a way. We have undiagnosed Canadians that will die if they don’t get treatment. It’s your job to actually help with this.”

Rourke and REACH are seeking the approval of a second self-test (OraQuick) and have ordered 60,000 INSTI kits to be passed out by community groups, making up for the lack of government purchases. Distributing these kits now is especially important.

“With the pandemic, we know that sexual health testing has been greatly impacted,” says the Community-Based Research Centre’s (CBRC) Chris Draenos. CBRC, which conducts Canada’s largest and longest running survey on queer and trans health, called “Sex Now,” noted the number of gay, bi and trans guys accessing HIV testing halved when the pandemic started. To help buck these trends, CBRC is one of the community organizations REACH is working with to distribute self-tests—with a plan to mail three free kits to as many as 5,000 people who request them through the just-launched 2021 iteration of the Sex Now survey.

“Some people may use all three kits themselves, others will pass them onto their social or sexual networks,” says Draenos. “We think it’s going to be a very effective way to distribute self-tests through community connections.”

Until manufacturers and governments come to the table, community organizers will continue to do the work themselves, says Rourke.

“HIV is not over yet, the numbers are not going down. We have the tools, it’s about doing the right things. We can change this.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra