If there’s one thing all of Canada’s political parties agree on, it’s cracking down on sex at all costs.

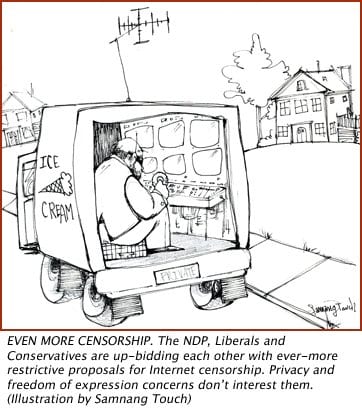

So it shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise that MPs from three different parties have put forward private member’s bills calling for far greater Internet regulation, surveillance and criminal prosecutions. Nor should it come as a surprise that all three bills are happy to sacrifice privacy and freedom of speech concerns.

Now, while the odds of a private member’s bill even coming to a vote in Parliament are long — it’s already too late for the current session — the three bills provide an alarming look at the sort of legislation that could soon come before Parliament. They also provide an opportunity to look at the implications of such bills in the light of how previous bills and rulings have been enacted.

The three bills are being put forward by NDP MP Peter Stoffer (from Nova Scotia’s Sackville-Eastern Shore riding), Liberal justice critic Marlene Jennings (from Quebec’s Notre-Dame-de-Grâce-Lachine riding) and Conservative Joy Smith (from Manitoba’s Kildonan-St. Paul riding). Stoffer was the only one to grant an interview.

Stoffer’s bill would require Internet service providers (ISPs) to monitor the activities of their clients, and would hold them criminally and financially responsible for any illegal material posted online by those clients.

“If you rented your house to Hell’s Angels, you could be held responsible for anything they did,” says Stoffer. “The ISPs have some responsibility to monitor sites, and if they see something suspicious, they have a responsibility to report it.”

Stoffer dismisses the cost to the ISPs, as well as privacy concerns and, indeed, any other objections to his bill, by invoking the need to eliminate child pornography.

“What’s the cost of protecting our children, of protecting society? The privacy advocates can go pound sand as far as I’m concerned. I have two young children. We should do everything in our power to protect children. I don’t believe in capital punishment, but I’m willing to make an exception. If it was my children, you wouldn’t have to worry about the law.”

When asked about the arguments ISPs have made that they’re being singled out over, for example, Bell Canada, Stoffer admits they have a point, but says he doesn’t care.

“They can draw a valid argument and say go after the phone lines. I’m going after them.”

Unbidden, Stoffer also volunteers that queers should support his bill because of the negative stereotyping they face around child porn — and manages to add to the insult by making the “some of my best friends” argument.

“I hate the linking of gays and lesbians to pedophilia. I know many of my friends who are gay and lesbian agree with me on this.”

But Stoffer is less sensitive to queer concerns when it comes to how the new age of consent bill might affect his bill. The bill to raise the age of consent from 14 to 16 — except for anal sex, which remains at 18 — is awaiting only Senate approval, but Stoffer is blasé about how his bill might affect teen sexuality, which often expresses itself on the Internet. Nor does he worry about such a bill depriving teens of information about sex or driving their sexuality further underground.

“You know what teenagers are like. I was 15 years old once. But if you’re a 17-year-old having sex with a 13-year-old, that’s illegal. If you have two 15-year-olds, that’s legal. I would hope we could separate the two.”

Stoffer also seems unclear on what exactly is considered to be child pornography. He refers to the case of John Robin Sharpe — who was charged, though acquitted in 2001, with possession of child porn based on stories and illustrations he had created from his own imagination — and admits he doesn’t know whether that’s illegal.

But the fact is that Bill C-2, which passed in 2005, widened the definition of child porn, and of legal sex, considerably, even calling genuine works of art or imagination into question.

When the bill was being debated, Egale Canada complained that the law created a definition of child pornography that is too broad and defences that are too narrow. The bill removed artistic merit as a defence and requires an artist or writer to prove the work fulfills a “legitimate purpose” — a term which the law does not define and threatens artists with expensive legal cases.

The law now also actually goes further than even the change to the age of consent. Under Bill C-2, any sexual relationship in which a person under the age of 18, even if they’re over the age of consent, is involved with someone over the age of 18, could be considered “exploitative” and illegal. If a judge is opposed to teen sex, or offended by an older gay man involved with a 17-year-old male, the judge could make the sex illegal.

If such a law is applied to the Internet, the possibilities of abuse are legion.

Even so, Stoffer’s bill may be the lesser of three evils. While it may be hypocritical, Stoffer says he doesn’t want the police to have free access to people’s Internet use.

“ISPs are still part of a private business. But with the police, it would be like letting them walk into a home without a warrant.”

The other two bills have no such qualms. Jennings — who attempted to shut down debate over age of consent at the justice committee after promising the queer community a chance to air its views — wants to force ISPs to include monitoring and data collection technologies to help police prosecute offenders.

The problem, of course, is that when such general information is collected, no one knows exactly where it goes, or what police might decide is relevant. Certainly, if police decided to go after public gay sex, Internet access would aid them immensely.

But even Jennings’ bill pales in comparison to the one put forward by Joy Smith. Smith’s bill contains the elements of the other two bills, but also would require ISPs to open up data networks to searches at the whim of the minister of industry. And although the bill doesn’t specify how it would be accomplished, the minister would also have the ability to censor “child pornography, material that advocates, promotes or incites racial hatred, and material that portrays or promotes violence against women.”

The bill pointedly doesn’t mention eradicating homophobic material, but the segment on portraying violence against women should raise red flags with anyone who’s followed the Little Sister’s case and the repeated seizures of SM-themed material.

The standard for such material was set in 1992, in the Butler case, when the Supreme Court Of Canada ruled that material that was “degrading and dehumanizing” was obscene. The ruling prohibited “depictions or descriptions of sex with violence, submission, coercion, ridicule … which appear to be associating sexual pleasure or gratification with pain and suffering, and with the mutilation or letting of blood from any part of the body.”

Immediately after the ruling, Toronto police charged Glad Day bookshop with selling the lesbian magazine Bad Attitude. A judge decided it was obscene. The same year, a judge used Butler to determine that five shipments seized en route to Glad Day in 1989 were harmful and degrading, and therefore obscene. The shipments included mainstream gay porn mags like Advocate Men, In Touch and Play Guy.

And Canada Customs used the Butler ruling to specifically target Vancouver’s Little Sister’s bookstore, even after the Supreme Court warned them in 2000. In 2001, Customs seized two volumes of an anthology of gay adult comics called Meatmen. Customs later seized two collections of gay erotic fiction, Of Slaves And Ropes And Lovers, and Of Men, Ropes And Remembrance. Little Sister’s is still appealing those cases.

If police and Customs are given the ability to access all Internet material at will, the Little Sister’s and Glad Day seizures could become mere trickles in a flood of seizures of queer porn.

The one bright aspect is that Stoffer says he doesn’t see any government — even Stephen Harper’s — bringing forward such a bill as official policy. He says privacy is still seen as a touchy subject for voters.

“Privacy, they’re afraid of that, of a constitutional challenge.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra