AM Homes is a writer with a reputation for looking at the world from a different angle and featuring characters on the margins. The End Of Alice, for instance, told the story of a convicted paedophile through his relationship with a young woman who was pursuing a young adolescent boy. In 1993’s In A Country Of Mothers she took on adoption, identity and obsession through the relationship between a therapist and her client. Homes is also known for her work as a writer and producer on The L-word a couple of seasons ago.

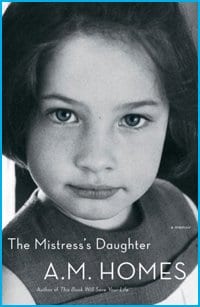

The Mistress’s Daughter, her first foray into memoir, tells the story of her adoption and eventual reconnection with her birth parents. This is not a happy story of reunion and Homes uses the experience as a starting point for a long and somewhat tortured meditation on the nature and meaning of identity in the most primal sense.

Homes was 31 when her birth mother contacted her — actually, she contacted Homes’ adoptive parents through a lawyer — setting in motion a bizarre series of events and triggering an emotionally tumultuous couple of years. She finds her birth mother difficult, demanding and incredibly needy, while her birth father comes across as a pompous jerk who insists that they undergo DNA testing to prove that she is really his child.

At the same time she is utterly fascinated to learn about the circumstances of her birth. Ellen, her mother, became involved with Norman when she was 17 and he was 31. He was her boss and he had a wife and two children. In spite of his repeated promises that he would leave his wife, he never did. Their relationship continued for five years and ended only when Ellen became pregnant (at around the same time as Norman’s wife). It was in 1961 and neither illegal abortion nor single motherhood appealed to Ellen and a private adoption was arranged. Homes grew up knowing that she was adopted but beyond that she knew nothing about her biological parents.

Homes has a particular interest in questions of origins, heritage and identity. Her interest reaches beyond basic biological information and into much more abstract territory like attachment and connection. She actually believes that sharing genetic material creates a bond and implies a relationship between individuals. The facts of biology are certainly inescapable but their meaning is highly subjective.

She becomes obsessed with finding out more about her genealogical heritage, particularly when Ellen dies five years after the reunion, and she writes about this in great detail. Her research takes her to countless archives where she studies a variety of documents — birth certificates, court cases, marriage licences, records of committal — all of which help to solve the mystery of who she is. At the same time the searching creates a new set of false trails, loose ends and unanswered questions.

Homes creates a compelling narrative about this quest and is brutally honest about the ways in which her search borders on the neurotic and is overly sentimental. She admits, “I am reading a pile of clothes, a messy house, looking for information, clues… there is a tendency to romanticize the missing person — to think about her is to allow her in. I hear her voice in my head — unreliable though she was, she is the only one who could explain to me what happened.”

But investing her mother with the power to explain what happened is flawed, in part because of her instability but more because the slipperiness of the question in the first place. Why would her mother’s memory of the story be any more satisfying or authentic after more than 30 years? Memory is no more fixed than identity and is subject to a multitude of forces only one of which is the current concept of genetic material.

It’s clear that the value Homes places on blood links comes from her sense that her connection to her biological parents was severed, but there is something deliberately irrational about her insistence on the primacy of that type of connection. There are other kinds of bonds that are meaningful and other forms of attachment that are significant but Homes certainly doesn’t acknowledge them in the book. While ultimately somewhat frustrating, the book is a fascinating look at the native life of a very skilled writer.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra