Rob Browatzke was used to spending 60 to 80 hours a week at Evolution Wonderlounge, the gay nightclub he owns in downtown Edmonton. As the only LGBTQ2 bar in northern Alberta, it’s the place you might find up to 600 patrons on a weekend, or spend more sedate evenings playing pool or trivia.

Then came COVID-19, and the indefinite shuttering of his business’s doors until it’s safe for clubgoers to return. Now, Browatzke is spending that time at home. But unlike those lucky enough to keep working from home with their paycheque intact, his business is completely stalled. “We’re hemorrhaging rent, insurance and other miscellaneous bills at about $25,000 a month with zero revenue,” he says.

Having closed in mid-March, just before Alberta’s provincial shutdown order, he had to hit pause on the bar’s Drag Superstar and Burlesque Superstar contests, multi-week live competitions awarding a crown and cash to local performers. He also had to lay off most of his 20 staff. Months later, non-refundable deposits on entertainers sit waiting for an indeterminate date in the future when the bar can host the event and make back the outlay.

While business owners of all backgrounds are dealing with the fallout from COVID-19, queer and trans owners are particularly feeling the pinch. Businesses serving the queer community, like bars and bookstores, have been in decline for many years. One researcher suggests as many as 37 percent of LGBTQ2 bars in the United States shuttered between 2007 and 2019. And as COVID-19 keeps patrons at home, spaces considered vital to LGBTQ2 communities are struggling doubly as hard to stay afloat.

Across North America, queer businesses are already announcing their permanent closures. Halifax bar Menz & Mollyz closed after 15 years, leaving only two gay bars in Atlantic Canada. Also departed are BT2—open since 2012 in a leafy plaza in the Austin, Texas, suburbs—and The Stud, a 55-year-old bar claiming to be San Francisco’s oldest. A former manager of The DC Eagle, a Washington, D.C., leather bar that opened in 1971 and announced its closure in May, says the bar’s end felt inevitable. “We don’t blame the pandemic per se,” Miguel Ayala says over email. “It just accelerated what [it] seems was already coming… depriving us of a chance for a proper farewell.”

There’s a lot of talk of resiliency and creativity during the pandemic—entertainers holding digital drag shows, or shops that once focused on analog sales going digital. But while there’s plenty of discussion about financial support for small business owners, queer business owners are finding it difficult to access and are, in turn, imagining what their post-COVID-19 future looks like.

Applications for commercial rent relief didn’t open until late May, despite many businesses having closed in March—and it’s up to the landlord to decide whether or not to apply. At the time of publication, Browatzke says his landlord is still considering it. And because most of his 20-person staff have been laid off, wage subsidies aren’t any help.

Browatzke is not coy about the possibility of closing. “That’s certainly a risk,” he says. “Bars and restaurants in Edmonton are already announcing permanent closures. It’s just not sustainable.”

Queer business owners have often had to do more with less and managed to survive. They’ve also faced the e-commerce boom and hookup apps, recession and neighbourhood gentrification. Could COVID-19 be the final straw?

Amid the chaos, our communities may finally have the chance to start a conversation about the particular challenges LGBTQ2 businesses face—and how we can help them better access what they need to thrive.

It’s still too early in the pandemic to fully realize the long-term economic impact of COVID-19. Given the lack of a consistent definition of this “new normal” and the possibility a vaccine may be more than a year away, a lot is uncertain.

That’s compounded with the fact that there’s not a lot of research on LGBTQ2 entrepreneurs and their small businesses. This is, in large part, because it requires entrepreneurs to self-declare that they are LGBTQ2, but it’s not always asked and not everyone feels comfortable self-identifying.

According to Darrell Schuurman, co-founder and CEO of the Canadian Gay and Lesbian Chamber of Commerce (CGLCC), about 2.5 percent of Canadian small businesses are LGBTQ2-owned. But he suggests that number is low because of the aforementioned reticence to self-identify. According to the CGLCC’s website, research suggests there are as many as 140,000 LGBT+-owned businesses in Canada. (Based on that number, at least 8.5 percent of small businesses across the country are queer- and trans-owned.)

And recent polling suggests these LGBTQ2 entrepreneurs are particularly hard-hit by the pandemic. Based on a CGLCC survey of their Certified LGBT+ Business Enterprises, 46 percent of respondents describe business conditions as bad, 42 percent say they’re middling and about 80 percent have lost revenue. There’s also been a 35 percent reduction in staff from mid-March to May, according to the survey, and two in five business owners think the federal government is not doing enough to support LGBTQ2 owned businesses.

Another survey from the Canadian Women’s Chamber of Commerce and Dream Legacy Foundation looked at underrepresented entrepreneurs, including 29 respondents identifying as LGBTQ+. In their survey, 69 percent of LGBTQ2 founders reported loss of contracts, customers or clients as their top challenge. Comparatively, only 34 percent of other small businesses across Canada reported loss of contracts as having a high impact on their company.

“Government programs to support small business owners are not set up to be exclusionary of queer and trans folks, but often end up serving cishet people”

Waverly Deutsch, a clinical professor and academic director of entrepreneurship at the University of Chicago, says LGBTQ2 business owners are also more likely to run into funding challenges. “They’re less likely to have outside equity funding than a comparable small business by a straight entrepreneur,” she says. “So their safety net isn’t going to be as good as other small businesses’ safety nets might be.”

When it comes to government programs to support small business owners, Deutsch—who co-authored the report “The State of LGBT Entrepreneurship in the U.S.” for StartOut, a U.S. LGBTQ2 non-profit geared to increasing queer and trans entrepreneurs—says they’re not set up to be exclusionary of queer and trans folks, but often end up serving cishet people. “I think we could easily see that with the response to COVID-19,” she says.

As the economy restarts, Deutsch says it will be important to see whether the policies to help restart the economy pay attention to LGBTQ2 and other minority businesses who have less access to standard forms of support.

When I reached out to Little Sister’s Book & Art Emporium owner Don Wilson in May, he spoke with me from the shop. In British Columbia, businesses like his weren’t forced to close but to adapt to physical distancing and other measures. So Little Sister’s stayed open, offering its usual range of LGBTQ2 books, adult toys, clothing and gifts to Vancouverites. But it wasn’t business as usual.

“Quite a few local people who live down the street have placed orders online or phoned-in and asked to have it delivered,” he says. “[They] didn’t want to come out.”

Bookstores, meanwhile, have fallen victim to e-commerce, and because queer ones are no longer the only place to purchase LGBTQ2 titles, they’ve been among the hardest hit. There’s no definitive listing for queer bookstores around the world, but in Canada, there remain just two—Toronto’s Glad Day Bookshop and Vancouver’s Little Sister’s.

Inside Little Sister's Art and Book Emporium in Vancouver. Credit: Riley Sparks/Xtra

Wilson says business declined by 40 percent in March, 35 percent in April, and 15 percent in May. He’s had to lay off five staff members and doesn’t expect them all to return. “I thought maybe more people would be reading during this [pandemic], but that’s not necessarily showing up in our sales,” he says.

He expects a 25 percent decline in sales over the summer, in part because the U.S.-Canada border is closed to the tourists who frequent the shop—one of a small number of LGBTQ2 bookstores globally. The cancellation of Pride celebrations in most major cities, including Vancouver, will also factor in.

But Wilson says, unequivocally, that while he’ll take a hit, the business isn’t in danger of closing. “I feel very comfortable at the moment that we’re not going to close,” he says. He adds that adult novelties and gift items help keep the store afloat. “If we were just a book business, we’d be dead in the water.”

Much like Rob Browatzke’s Edmonton business, Wilson doesn’t expect to receive any COVID-19 funding from the government—and he says his landlord, at the time of publication, isn’t planning to apply for rent relief.

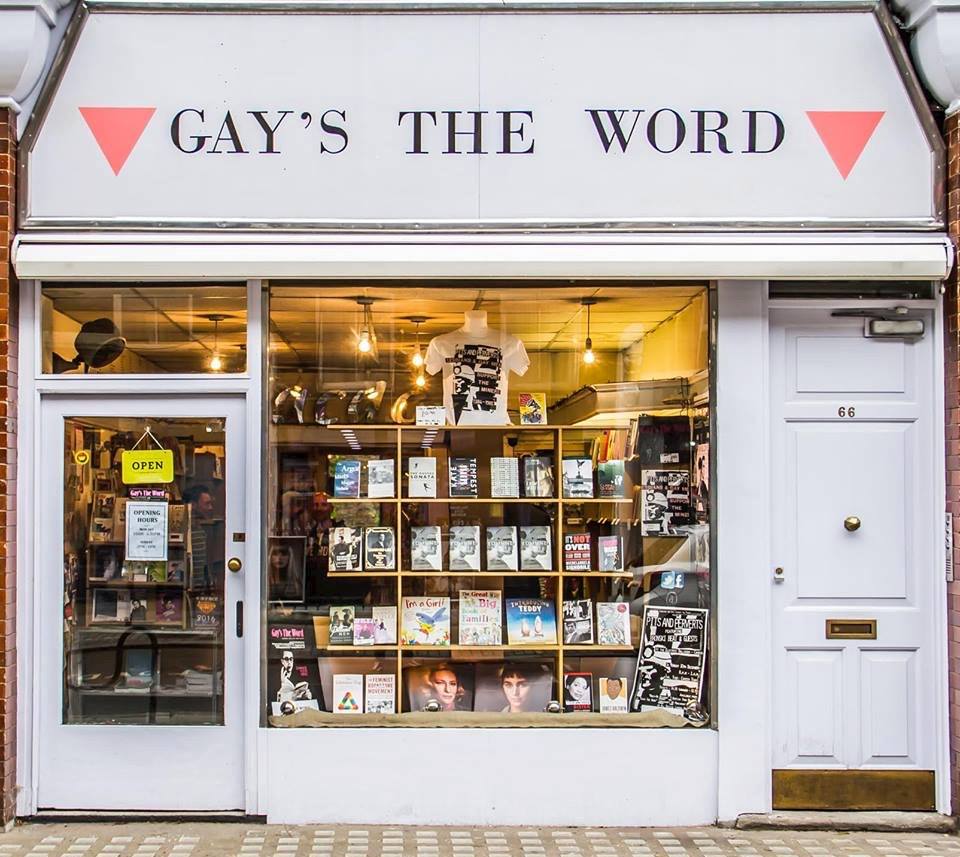

But in other parts of the world, queer bookstores have been able to receive government funding to keep their doors open. In London, England, Gay’s The Word—one of three LGBTQ bookstores in the United Kingdom—has benefitted from government small business aid.

London's Gay's the Word bookshop. Credit: Courtesy Facebook/Gay's The Word

According to manager Jim MacSweeney, “The government hasn’t handled lots of things particularly well, [but] they’ve been good for small businesses, allowing us to furlough staff where the [government] pays 80 percent of wages to a certain limit, abolishing business rates for a year (a tax which for us is about CAD $20,000) and providing a small business grant that is not repayable, for CAD $42,000.”

In March, the shop closed entirely and suspended mail order, directing customers instead to the two other queer book retailers in the United Kingdom. The store plans to reopen July 1.

But MacSweeney acknowledges being fortunate. “We have no idea when gay bars, clubs, theatres and restaurants will reopen,” MacSweeney says. “So for them, the future must look fairly bleak.”

Bet-z Boenning, owner of the Milwaukee, Wisconsin, lesbian bar Walker’s Pint was supposed to be gearing up for Pride week, a Bucks NBA championship and the 2020 Democratic National Convention this summer. Instead, she’s watching bars and restaurants in the city’s suburbs open while the Pint, like other queer bars in the city proper, has been closed since mid-March.

“You just kind of watch your savings disappear little by little, and that’s years of saving,” she says. Boenning, who opened Walker’s Pint in 2001, has received a “small” Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan from the federal Small Business Administration and is hoping to get some funding from the city of Milwaukee. Even though her landlord has been accommodating, it’s still difficult.

“‘You just kind of watch your savings disappear little by little, and that’s years of saving,’ says lesbian bar owner Bet-z Boenning”

Four lesbian bars in Milwaukee have closed in the last 20 years, leaving Walker’s Pint on its own in that category. Media reports suggest only 16 lesbian bars are left in the United States. “Lesbian bars in general are pretty hard to keep afloat,” she says.

Boenning thinks it’s because now many queer women can assimilate into straight bars more comfortably, which gives them a lot more options than they may have once had. This means these bars in particular may be disproportionately affected among queer bars during the pandemic.

Though the city said she could open for curbside business, without a kitchen she’d be limited to selling some bottled beer products—“a to-go liquor store type of a thing.” “It doesn’t even make sense to do that for me.”

Inside Walker's Pint in Milwaukee. Credit: Courtesy Facebook/Walker's Pint

Right now, even opening at limited capacity looks appealing and lucrative in comparison

In Austin, Texas, The Iron Bear is living this new reality—and just in time. Bengie Beshear says the gay bar couldn’t afford to wait: Another month and they could have had to close. Because they have a kitchen, they tried briefly doing takeout, but with about $200 a day in revenue it wasn’t worth the effort.

Beshear says he felt “cautious” prior to reopening May 22, but opening at 25 percent capacity has presented its own challenges. “I thought we’d planned enough but we did not plan enough, and I think I underestimated the amount of people that are wanting to come out.” He says it’s been a “full house” every night—about 50 people compared to 200, with a jukebox as the only entertainment.

“For however long the ‘new normal’ lasts, LGBTQ2 bars can expect lower revenues, smaller crowds and an increased workload”

And The Iron Bear needs every customer. The bar just opened a new location before COVID-19 hit, and anticipated revenues from events like a major gay softball tournament and the SXSW festival have disappeared. A PPP loan, totalling about USD $30,000 helped cushion the blow somewhat.

Having had 25 staff prior to the pandemic and reopening with just eight, the labour pinch has been acutely felt.

“Usually two bartenders and 50 people—they’re bored,” Beshear says. Now staff spend extra time walking back and forth to serve customers at tables, instead of letting them order at the bar. This impact on labour hadn’t occurred to Beshear before reopening. On a recent night, there was a 20 minute wait for a drink. Now, as the bar plans to increase capacity to the now-permitted 50 percent, it’s advertising to fill vacancies.

For however long the “new normal” lasts, LGBTQ2 bars can expect lower revenues, smaller crowds and an increased workload. Without a reliance on performances or mingling freely with LGBTQ2 strangers, they’ll have to cut out elements separating them from the pack just to reopen the doors, survive—and, if they’re lucky—thrive.

In Edmonton, Rob Browatzke isn’t sure when he’s going to reopen—it depends on when Alberta’s government feels confident moving to their third stage of reopening. It’s uncertain when that will be—the second stage only launches on June 12. But he knows that some of the entertainment mainstays—pool tables, karaoke, drag shows and a crowded dance floor—aren’t going to be part of the equation. Not yet anyway. He also muses about the potential for added travel costs or border restrictions when it comes to rebooking or bringing in outside guests—yet another expense for his bar.

Like Little Sister’s owner Don Wilson, Browatzke knows this year involves less revenue. But the pandemic means a lack of fundraising for local LGBTQ2 groups, too. Browatzke estimates about $350,000 has been raised for the local queer community through fundraising activities like shared revenues from events, 50/50 draws and silent auctions since the bar opened in 2013. He figures at least $50,000 would have been raised during the period the bar has been closed—$20,000 from Pride events alone. If queer-owned businesses that give back to the community disappear, what will happen to those community-driven efforts? Who will fundraise or create space for the community in their wake?

Browatzke knows it would be a huge loss if his bar were to close. Sure, patrons could still go to other bars, see drag events elsewhere and cruise online. “But are these other venues going to feel the sense of obligation to mentor the community, to provide meeting space for community groups or to host all these different fundraisers to put all this money back in the community?

“I don’t see that happening from the venues that are hosting these events,” he says. “They’re there hoping for the profit, but I don’t see that profit going back out into the community.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra