Saying that queer female sexuality was repressed in the 1800s is a little like saying Queen Victoria could have stood to lose a pound or two; in other words, nobody dared speak publicly about either.

“Back then there was no concept of women having sex,” says Toronto actor Ellen-Ray Hennessey. “If you weren’t married, you didn’t have sexuality. The sexuality came through the man, so there was no idea of lesbianism.”

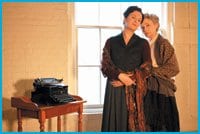

Hennessey is prepping for her role as Virginia Madsen, one of three spinster sisters in Linda Griffiths’ play Age of Arousal. The story revolves around that trio and two other unmarried women, all feeling invisible and of little use in a world that celebrates the male workforce and compliant wives who know their place.

“It’s a really budding, cresting period in female history,” says Hennessey. “Women didn’t have the vote yet; they were still owned by their husbands.

“There were so many more women than men in 1875, unmarried and largely thought of as redundant. The character Rhoda calls them ‘odd women.'”

The sisters live in near-penury, with Virginia and older sibling Alice investing their failing hopes in young Monica’s prospects for marital security. With no suitable men on the horizon, the trio answers an invitation to attend a secretarial school run by militant feminist Mary Barfoot (Clare Coulter) with her business partner and lover Rhoda (Sarah Dodd).

Mary’s in her 60s, retired from the front line of the suffragette wars. Settled into comfortable domesticity with Rhoda, the two embark on the new frontier of training women for the workplace. The Madden sisters settle into a genteel sort of existence with their lesbian teachers at the school, until the arrival of rakish Everard, cousin to Mary, wreaks unintentional havoc on the women’s lives.

Everard (played by Dylan Smith) considers himself a progressive sort. He’s fascinated by the emergence of these “modern women” who support and think for themselves, eschewing control and comfort from any man.

Naturally, this eligible bachelor catches Monica’s eye but hers is not the only interest piqued by the dashing young man; an unexpected third party throws her hat into the romantic ring.

“There’s a huge tension in the play,” director Maja Ardal explains. “There’s sexual awakening but there’s also a whole new dialectic around male-female relations and how to reconcile feminist ideals with traditional marriage — or even, for that matter, with one’s own lust.”

Apparently it’s not just wee Monica getting moist over delectable Everard; dirty thoughts about the handsome lad are springing forth from some highly unlikely, ladylike minds.

“Everybody in this play has a secret,” says Ardal, “and characters will actually speak thoughts and things that you could never say out loud in a thing that Linda calls ‘thought speak.’ It invites the audience into a deeper level of the characters.”

Griffiths has employed this tool to great effect in other plays, notably The Darling Family and her hit Maggie and Pierre. She has said that she utilizes “thought speak” where the subtext is so important, and so different from the dialogue, it becomes part of the text itself. In Age of Arousal this approach allows the audience to become privy to the inner struggles of repressed women attempting to couch their atavistic compulsions in socially acceptable — if ambiguous — terms.

It is the way we find out, for instance, that the outwardly staid Virginia harbours a desperate desire to dress in men’s clothing and live as a male. It is also the doorway into the other gals’ licentious thoughts regarding dear Everard that would make Queen Victoria blush right down to her Directoire knickers.

“Obviously it wasn’t socially acceptable to be a slut,” says Gemma James-Smith, playing Monica for a second time since the play’s original production in Calgary. “There’s a real push and pull of wanting to explore these feelings, while not wanting to be thought of as common.

“I think Monica is trying to find her balance in that. She’s trying to break away and grow up, but it’s hard when she’s being held with such a tight hand… especially by Virginia. She’s really been restrained from exploring.”

If Age of Arousal seems to have a very contemporary bent, it’s with good cause. Griffiths had originally set out to write a straightforward costume drama based on George Gissing’s 1893 novel The Odd Women but ended up dissatisfied with the results. Once she began to incorporate a modern sensibility the play began to take shape as an amalgamation of old and new themes.

“People assume that costume dramas are kind of boring and staid,” Griffiths says. “I wanted to kick that out while still having anachronism. I’m not interested in things being subtext… why does everything have to be underneath?

“This play is a real challenge to Merchant Ivory stuff. All of the language is of the period, but it’s robustly of the period.” The Nightwood Theatre production features period set and costume designs by Julia Tribe, lighting design by Kimberly Purtell and music by EC Woodley.

Griffiths’ passion for history served her well in researching and fleshing out each character, making the women believable while still accessible to present-day audiences.

“I love time travel so much,” she says. “I especially love exploring modernity through that historic perspective. This is a contemporary play set in the past. One character is not interested in sex that much, one is bi and one woman is fully realized as being gay. There were very underground gay women. How careful they had to be is one of the things explored here.”

Coulter (Away from Her) has her own take on the challenges faced by her character, Mary.

“She’s been through these terrible things as a suffragette,” the actress says, “being force-fed and nearly crippled in prison. Mary’s abandoned the movement now and feels fighting for the vote is not enough.

“She wants women to be independent financially by teaching them to make money, but she berates herself for not wanting to go to jail or on hunger strike anymore… for having what she thinks of as a soft life.”

Coulter was immediately drawn to the character’s story, having recently marvelled at Judi Dench’s darkly complex role as an unlikable, closeted lesbian in the film Notes on a Scandal.

“It made me realize that you have to be much more subtle about playing someone who is disappointed in something they don’t have,” she says. “At first I thought that Mary, like Judi Dench’s character, was a predator, but now I see that they’re both clever in the sense that some gifted people are, without the drive to actually achieve the things they want.”

Also appealing was the chance to work alongside Griffiths again; the two shared a stage in productions of The Master Builder and As Far as the Eye Can See.

“The thing that’s fun about Linda is that she likes to shock, surprise and pervert other people’s expectations. It’s both challenging and immensely pleasing.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra