I’ve been binding my chest since I was a teen—which means for over 25 years. Much like how my gender identity has evolved over this span of time, so have my varied binding techniques. I first started with gauze wrapped unrelentingly tight around my upper torso held in place with safety pins that tended to come loose throughout the day, poking me in the ribs and arms, after which I’d emit pained yelps before excusing myself to the nearest bathroom. In my later adolescent years, I switched to using less cumbersome electrical tape—though doing so left me with a few nasty open wounds which later scarred. A friend once noticed the tape and asked me about it. I said I’d been injured. That was my go-to excuse whenever “my secret”—the breast binding—was discovered: “Oh, it’s nothing,” I’d respond as casually as possible. “I got stabbed.” Over the next couple of decades, I tested several other binding methods: Sometimes I doubled up on sports bras, or I’d wear one sports bra forward, the other backward. I layered sports bras and Spanx tank tops for a long time before finally learning (at the age of 30) that actual chest binders with clasps—essentially sports bras with enough elasticity to stretch and flatten my chest—were available for purchase online. So I bought a few and, over time, bought about a hundred more. I’m now in my late 30s. I identify as non-binary because, well, I’ve always considered myself “non-binary”—though I didn’t know about the proper distinction in my youth. (Did it even exist ?) I’m a masculine person with a distinct feminine side. I’m a feminine person with a distinct masculine side. I’m both. I’m neither. I’m more. There remains, however, one part of my body with which I’ll never identify: My breasts. So, last May, I decided that it was time for top surgery. The only problem: I knew very little about the process of getting top surgery. Turns out, it’s a lengthy, frustrating one—not only for myself but also for others with whom I’ve spoken. The expected range of cost, for instance, is quite a gap to consider: In both the U.S. and Canada, top surgeries run anywhere between $3,500 to $10,000 USD, depending on one’s insurance coverage—or lack thereof. That’s not including consultation fees, required pre-surgery appointments (electrocardiogram—EKG—blood panels, etc.) and post-surgery appointments. Nothing happens overnight. I knew better than to expect top surgery to be a breeze, insurance or no. Still, my personal experience has been an exercise in patience, financial acumen and self-advocating.

Initially, I didn’t intend to use my insurance for the surgery. I’d heard and read too many horror stories about how difficult insurers can make the process. And I was adamant about not undergoing hormone therapy, which I assumed was a coverage requirement at the time. Three months into my sans-insurance endeavour, however, I realized the full financial gut-punch I was facing: About $8,000 USD for the surgery alone, not including anesthesia and pre-operative requirements (which included, for me, an echocardiogram, an EKG, and a complete blood count panel—each of which meant separate medical bills). Plus, there were the appointments I’d need to make with my general practitioner to even secure these specialized tests. So, after a week or so spent mulling my options, I nixed my sans-insurance surgery plans and opted to go with insurance instead. I will tell you now that this was a smart decision. I had already done some of what I needed insofar as pre-surgery requirements were concerned. I would later learn the stipulations are largely the same with or without insurance (meaning, if one pays for top surgery out of pocket, the surgeon will also ask that certain prerequisites to be met). At that point, I had:

- A letter of “informed consent” attesting to a gender dysphoria diagnosis from a licensed mental health provider

- The ability to make informed decisions and to consent for treatment

- The age of majority in a given country

- Any and all major medical/mental health issues reasonably well under control

What I needed next was confirmation from my insurance provider whether or not I would need to undergo hormone therapy. I had two opposing “experts” telling me “yes, I would” and “no, I would not.” What my insurer gave me, however, was absolute confusion. In fact, I wound up navigating the medical coverage process alongside representatives of the company, each of whom were woefully unaware of the specifics I requested whenever I wrote or called. And I wrote and called a lot. Here are a few of the responses I received from insurance reps either over the phone or by email:

- “To find out the estimated allowance for top surgery, please go to…the ‘Tools’ tab and select ‘Treatment Cost Estimator’ and read…” (There was no “cost estimation” available for “top surgery/gender affirmation surgery/chest reconstruction.”)

- “What is ‘top surgery’?”

- “Do you have gender dysphoria?”

- “Please review your specific plan for details about your concern.”

- “Please review your policy for specific details about your concern.”

- “Subcutaneous double breast mastectomies are covered. I hope you feel better soon, Ms. Higgs.”

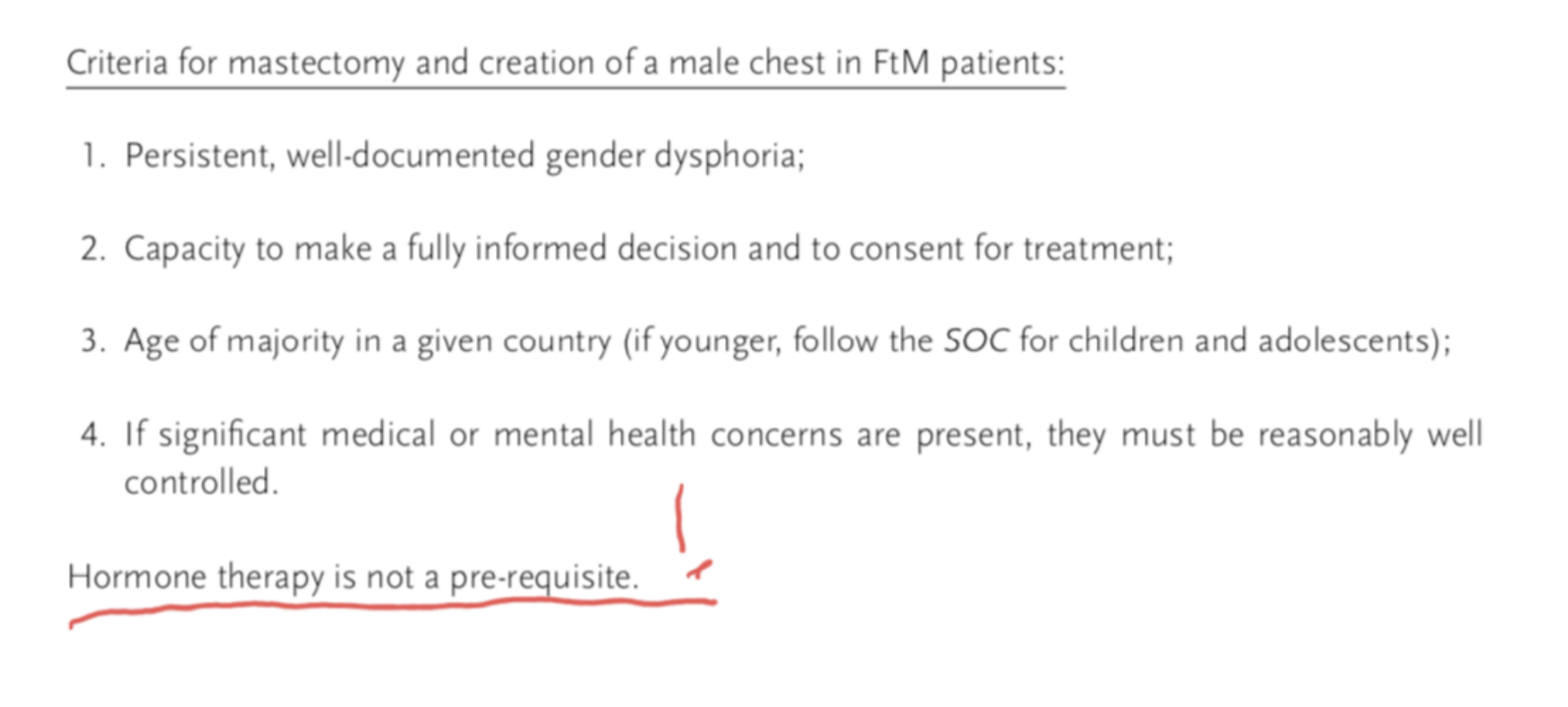

It took me awhile to realize that the insurance reps’ ignorance did not mean intractability on their company’s part. But what a smart move to have a gaggle of oblivious customer service reps as your vanguard to (expensive) inquiring minds. I persisted in spite of the disheartening responses I kept getting, chiefly because my friend Tosh Provancher would not stop saying, “No, your insurance must cover the procedure.” Tosh would know: They’re non-binary and underwent top surgery. They’re also a licensed clinical marriage and family therapist, who regularly writes “informed consent” letters for clients, which are letters of recommendation for gender affirmation surgery on the basis of a “gender dysphoria” diagnosis; almost all providers require at least one of these letters. “Most insurance policies mirror what the Standards of Care suggest,” Tosh said. “An appeal is worth engaging in if the initial claim is denied. Insurance can be hit or miss and really depends on your policy and your insurance carrier.” The Standards of Care (SOC) are recommended clinical protocols set forth by The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) for healthcare professionals to follow during their treatment of transsexual, transgender and gender nonconforming patients). These protocols are crucial, and most insurance providers do follow them. For me, their value lies in the following statement, found in the middle of page 59 of SOC’s latest volume:

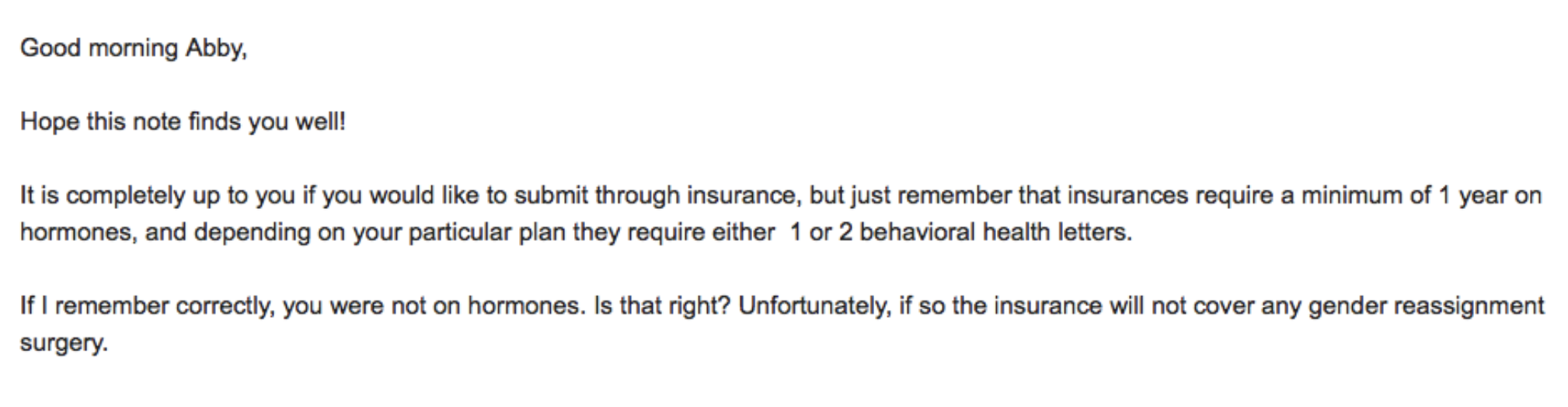

The non-essentialness of hormone therapy was—and is—important to me. I don’t want to take hormones. While the SOC does not separate “transgender male” from “gender nonconforming/non-binary” in the verbiage of its affirmation surgery criteria, it does say that those who do not wish to undergo hormone therapy aren’t required to. I’d initially opted for sans-insurance top surgery under the assumption that hormone therapy was required. Tosh, of course, told me 92 times that it was not. The office manager with whom I regularly communicated at a plastic surgeon’s clinic before I’d opted to go with insurance, on the other hand, told me that, yes, most providers require: “A minimum of one year on hormones, and depending on your particular plan they require either one or two behavioural health letters.” Since I was not taking hormones, she added, my “insurance will not cover any gender reassignment surgery.”

Looking back, I will give that office supervisor the benefit of the doubt and assume she was ill-informed about WPATH’s protocols on top surgery requirements and that she was not, in fact, trying to get me to undergo the procedure at her clinic at full cost. I mean, if the insurance reps don’t know squat, then a plastic surgeon’s office manager can be just as unwittingly ignorant. What I needed now was a definitive answer from my insurance company. So far, the closest response I’d received was the question, “Do you have gender dysphoria?” which meant someone on my provider’s end had a vague idea of what I needed for procedure approval. So, I called my insurance company one more time. The customer care rep on the line told me right away that she didn’t know what “gender-affirming surgery meant” and asked me to be more specific. This time, I skipped the phrase “subcutaneous double-breast mastectomy” and opted, squeamishly, for the term “sex-change operation.” As before, the rep put me on hold because she was pretty sure there was a different script for the kind of benefits explanation my inquiry required. When she came back on the line, she said, “For those without medical contradiction [the rep meant “contraindication” here] to hormonal therapy, 12 continuous months of hormone therapy is required.” “What does that mean?” I asked, frustrated. “Hold on, I’m not done” she said. “For those without medical [contraindication] to hormonal therapy, 12 continuous months of hormone therapy is required, unless undergoing FTM chest reconstruction.” I asked her to please repeat that last part of the sentence—the one starting with “unless.” “Unless undergoing FTM chest reconstruction.” And there it was—“unless undergoing FTM chest reconstruction.” That one disclaimer was my insurer’s convoluted, misinformed-about-proper-verbage way of stating: “Hormone therapy is not a prerequisite if you’re just getting your godforsaken tits chopped off.” “What does ‘FTM’ mean?” the rep asked. I was ecstatic. “Female-to-male! That’s my procedure! That’s me!” Except it wasn’t “my procedure.” That isn’t me. Not really. I am not transitioning. But, as far as my insurance provider was concerned, I am undergoing a “FTM procedure.” I don’t know why the “gender nonconforming affirmation” surgical designation doesn’t exist, much like how “gender nonconforming” is a sort of afterthought even with WPATH’s protocols. The rep confirmed one more time that my procedure—“Top surgery? Is that what you called it? I learn something new every day”—did not require “12 continuous months of hormone therapy” to qualify for insurance coverage. She then ran down my provider’s specific “medically necessary” requirements: One informed consent letter attesting to my “gender dysphoria” diagnosis and pre-authorization from a pre-approved surgeon (who would, in turn, verify that all the other requirements were in check). That was it. Finally. I had the answer I was looking for. The answer Tosh knew existed.

There’s a good chance my procedure will still be denied. That’s what many folks who’ve undergone the surgery with insurance have reported. Tosh said insurance can be hit or miss, but to remember that there’s always an opportunity to appeal. A study released in October 2019 confirms the capricious nature of insurance companies when it comes to top surgery approval. Upon the release of her findings, Dr. Yvonne Marsha Rasko, MD, affiliated with the University of Maryland School of Medicine, stated, “Our survey study finds marked variation in policy criteria for top surgery between insurers. These criteria often deviate from established global recommendations, and some insurers categorically deny access to gender-affirming top surgery.” While Dr. Rasko’s findings are disappointing, there’s no denying that the appeals process seemingly works well. Tosh knows the whole gamut inside-out. “I’ve even seen lawyers get involved,” they once told me. “There are agencies out there that help with that part, too.” In the end, it all comes down to investigating and self-advocating. Having someone like Tosh in my ear telling me to look deeper, look harder, ask more questions certainly helped. There are answers, and sometimes the folks who have them don’t even know they have them—such as the insurance reps. It may take some extra time and it may even mean a lengthy appeals process, but top surgery is worth the fight. Because you’ll likely win. And if you don’t have a Tosh egging you on, let me be them for you. The answers are there; go find them.

Line break image by photovideostock/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra