The seventies were a thrilling era of chiffon pies, extravagant parfaits, and endless variations on Baked Alaska. Not one to miss out on culinary history, I took it upon myself to make dessert for about a year’s worth of Sunday lunches for my family.

My preparations began on Saturday, when I accompanied my mother on her weekend shopping trip to Safeway. I was a silent and slouching figure habitually dressed in beatnik black, in the backseat of our red Volvo station wagon. This mute arrangement suited us both, each too dispirited to entertain the remote possibility of civil conversation. As a teenager, I thought silence and depression were status quo and that hours and days of muteness between a mother and her daughter was normal. I thought family was a desert you had to traverse to get to a place where people were curious, and got to know you and where there was a you someone would want to know.

At the glittering supermarket, we immediately parted ways. Off I went to the baking aisle to ogle McCormick’s Cream of Tartar, Lyle’s Golden Syrup, and Nabisco Graham Crackers. I lingered over the triumphant inventions of the western world, most of them absent from my mother’s pantry. After making my selection, I located my mother dolefully examining brands of liverwurst and pickled herring in the deli section. I dumped my items into her shopping cart, took the keys out of her purse, and didn’t look back when she said, loudly and embarrassingly, in Ukrainian, What is wrong with you? I returned to the car. The names of those items were the blank verse of a culture – American? English? Normal? – I desperately wanted to speak.

To Mama’s credit, I do not recall any of my ingredients, arcane as they were, getting tossed at the cash. Perhaps my mother was bemused by my eccentricity. Perhaps, of all the teenage peccadilloes I might have acquired (drugs, alcohol, an English boyfriend), this one was unbelievably benign.

I chose desserts only from decidedly non-ethnic sources, like Betty Crocker or The Pillsbury Cookbook. I adored the names of their creations: Tunnel of Fudge Gateau; Strawberry Chiffon Chocolate Pie. I basked in their confidence and scientific prowess: Every Recipe Perfected For You In Our Test Kitchens boasted Better Homes and Gardens New Cook Book. “It is our sincere wish that this cookbook may be of assistance to the women of Canada,” proclaimed The Blue Ribbon Cookbook. Indeed, the good people at Blue Ribbon had taken it upon themselves to instruct Canadian housewives on menu-planning. Every meal was to have one hot dish. Variety was crucial (“A meal where everything is whitish is unappetizing.”) Highly spiced foods and pickles were to be sparingly served. The Modern Encyclopedia of Cooking even instructed housewives on The Social Use of Food: “The dinner table is no place for any member of the family to air the grievances of the day, for the husband to take his wife to task for extravagance, for the wife to express her financial worries, for either of them to scold or discipline the children.”

My father was often belligerent at the table, and we kids felt no compunction in airing the grievances of the day. I was mortified by the plate of my Mama’s homemade dill pickles at every meal, the cold breakfasts, the whitish meals of perogies and sour cream. Dessert would be my corrective. Thus, on Saturday nights, while my female peers were going to movies, having sleepovers, engaging in the sweet, awkward rituals of dating, or the sweaty exigencies of teenage sex, I, like some miniature gay man, made dessert.

My baking binges took hours, sometimes days. I was enamoured of complex, multi-valenced concoctions, preferably those, like my beloved Baked Alaska, which involved both baking and freezing. Extremes of temperature and flavour were my specialty.

I had not yet resolved the uncertainties of my libido, was secretly worried about my profound disinterest in the Junior High Prom. It would be a quarter century before Will, Grace, and Ellen appeared on my television screen. Were the assertive flavours and temperatures of Fudge Ribbon Pie metaphor for my unacknowledged desires?

The making of Fudge Ribbon Pie begins relatively casually, with the combining of unsweetened chocolate squares and evaporated milk. Butter, sugar, and vanilla are stirred in, after which the mixture is cooled.

And then, all hell breaks loose. “Spoon half of the peppermint ice cream into a cooled pastry shell,” orders the cookbook, shrilly. “Cover with half the cooled chocolate sauce; freeze. Repeat with the remaining ice cream and sauce. Cover and freeze overnight.”

As if these hours of blending, rolling, baking, stirring, spooning, freezing, spooning and freezing again were not sufficient workout for a lanky, depressive teenage girl with hormones to burn, there was still the meringue: three egg whites beaten with vanilla and cream of tartar. “Gradually add 6 tablespoons sugar, beating till stiff and glossy peaks form,” demanded the cookbook in its relentless fashion. And then: “Fold 3 tablespoons of crushed peppermint-stick candy into the meringue.”

By then, my family had returned from church (I stayed in bed as they left, feigning a coma). My father, due to my utter lack of religiosity, was now shunning me. Mama heated roast beef, gravy and mashed potatoes in static, bristling silence, no doubt disturbed by my territorial incursion and its perceived critique of her cuisine. Roman, Mikey, Jeannie and Lydia were exhausted from a half hour each way of fighting in the car followed by ninety minutes of Byzantine Ukrainian Catholic worship, with its chronic standing and kneeling, its kissing of crosses and beating of chests. They were irritated and unsettled by a rambling sermon chastising them for every biological and psychological desire imaginable, delivered by a beet-faced priest desperate for his noontime glass of wine.

In short, my audience as I removed the pie from the freezer, spread the meringue over the chocolate layer, sprinkled the top with a remaining 1 tablespoon of crushed candy, placed the pie, for reasons unknown, on an old, unfinished wooden cutting board, and baked at 475 degrees for four to five minutes or until golden, serving at once, was less than ideal. By now they were soporific from their whitish servings of perogies, roast beef on the side, pickles on the side of that. My father, a diabetic, and my mother, a devotee of Weight Watchers, eyed my pie with fascinated revulsion.

My siblings consumed their enormous slices of Fudge Ribbon Pie in silence, and then left the table without a word. What could they do? The pie’s pop culture American flavours were delectable to them, but my mother’s disapproval transformed it into contraband. Mama had long since disappeared from the kitchen. Only my father and I were left at the table. He, freed from his wife’s watchful gaze, was digging into a second slice, smiling guiltily at me. I, coming down from the high of baking and serving, was left with an addict’s aftertaste: pride mixed with shame; cold and hot, juxtaposed.

After my year of extreme desserts ended, I entered into a decade-long dalliance with heterosexuality. I went on a handful of dates with theatrical boys; boys who read Nietzsche; boys who sang in the church choir. 100 percent of them turned out to be gay.

Who lives in silence and who gets to speak? I no longer disavow the girl who stood so silently and unhappily over the simmering pot of chocolate, waiting for the right texture to appear. I suspect the hot and cold temperatures, the desperate sweetness of those long-ago Sunday confections to be a language more genuine than speech.

Perhaps only my mother understood who I really was: a girl waiting and waiting, with regret and excitement — for subways and rented rooms, for cities and cabarets — for her life to begin.

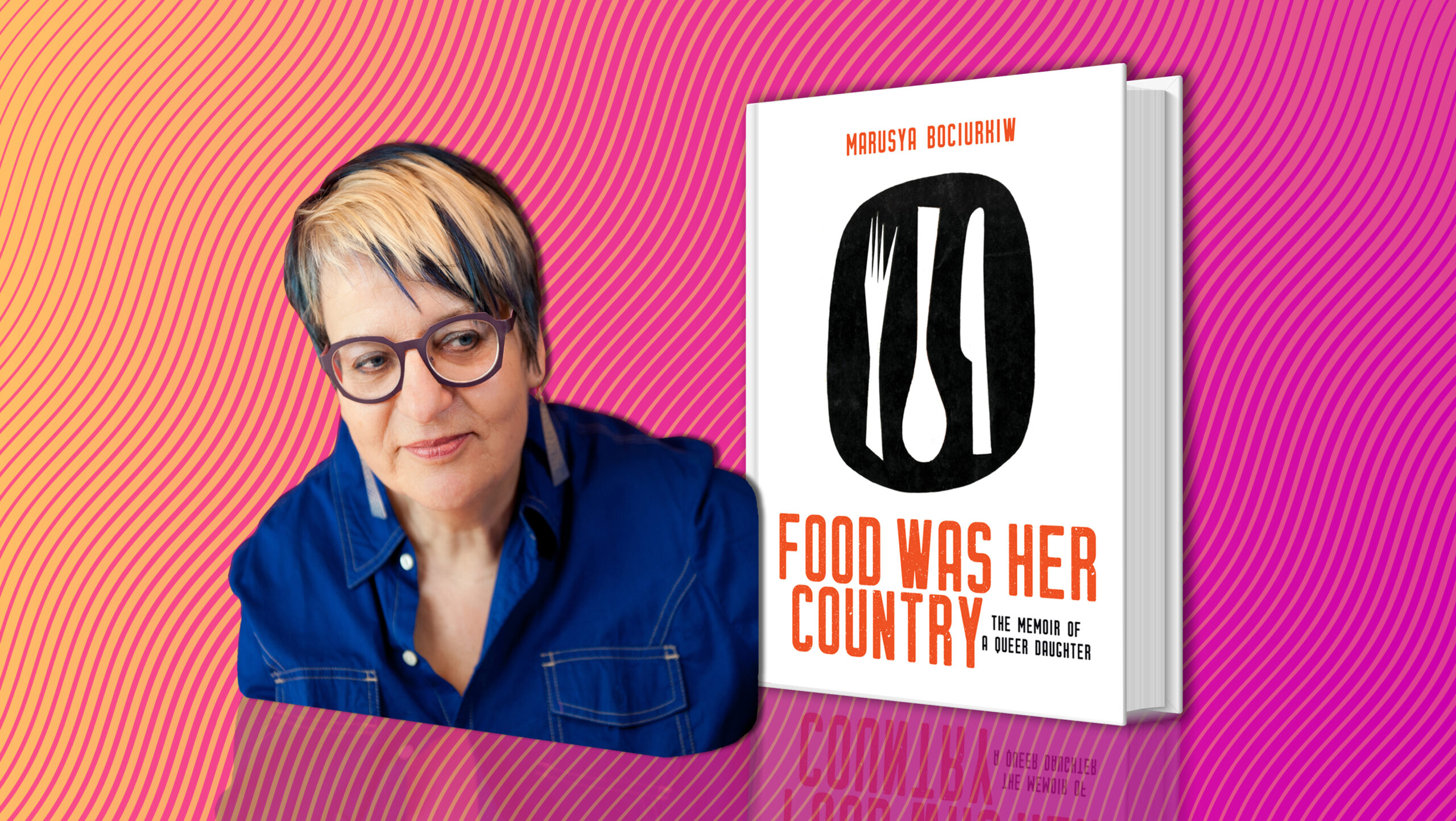

From the book, Food Was Her Country: The Memoir of a Queer Daughter, © 2018, by Marusya Bociurkiw. Food Was Her Country is a finalist for the 2019 Lambda Literary Awards in the category of lesbian memoir/biography. Winners will be announced on June 3 in New York.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra